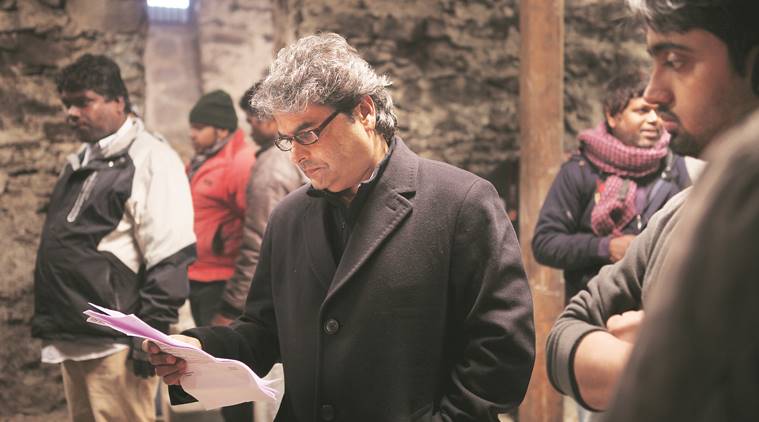

Vishal Bhardwaj’s Pataakha hits screens today.

Vishal Bhardwaj’s Pataakha hits screens today.

Having a foul-mouthed, recalcitrant teenager for a heroine is complicated enough for some filmmakers. But this is Vishal Bhardwaj, who has a proven record of taming the twins. In Pataakha, his latest and a relatively smaller outing compared to his last Rangoon, he uses the sisters as a metaphor for the strained relationship between India and Pakistan. Touted as a black comedy, the film is not exactly about twins, but Bhardwaj’s feuding sisters (Sanya Malhotra and Radhika Madan) are up to some twinning here. Are the twinning winning? That’s for the critics to decide. According to recent reports, the Bard expert is already working on an adaptation of Twelfth Night, which will feature twins — a brother and sister pair to be played by the same actor.

For long, Bhardwaj has engaged with the idea of twins, more as a way of reflecting the good-boy/girl and bad-boy/girl adrenaline rush than the Shakespearean confusion of mistaken identity. Kaminey (2009) and Makdee (2002) are prime examples of these. One can take the liberty to add that Makdee’s Chunni and Munni could have grown up to be Chhutki and Badki of Pataakha. Bhardwaj’s directorial debut Makdee established his passion for twins and dualities, through which he has explored the human complexities and follies. Call it pop realism, if you will. The filmmaker has often billed his cinema as fantasy, in a sharp counter to those critics who classify them under the realistic bracket. A children’s confection, Makdee is a highly enjoyable fantasy featuring twin sisters (Shweta Basu Prasad). Munni, studious and subservient, is the ideal daughter and as a result, the favoured one at home. Chunni is the stark opposite. She’s cheeky and not afraid to speak her mind. Locate your clue to the future Vishal Bhardwaj woman in Chunni. She dares to step into territories even men of the village dread. (Somewhat like the brave child protagonist of The Blue Umbrella who saves her wrestler brother from snake bite). She’s also the one with a sense of humour. When the school teacher condemns her to the typical Indian ‘murgha ban jao’ punishment, she says, snidely, “Main murgha nahin ban sakti.” Why, the teacher asks earnestly. Cue this zinger: “Main murghi ban sakti hoon.” Canned laughter. It’s appropriate, then, that the black sheep of the family wins the day in the end and feted finally, announces her return to the routine by freeing cage full of roosters from the local butcher’s stock.

Lurking beneath the simple-minded children’s fable is something far spookier — the ghostly presence of the witch (played by Shabana Azmi). And with that, we come to another Bhardwaj fixation: the witch as a device of evil design. In Maqbool (2003), the Indian seer of Shakespeare turns the three witches into a pair of astrology-obsessed narrators. Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri, old friends and stalwarts of parallel cinema, are reimagined by the Bard-loving director as greedy cops who predict Maqbool’s (Irrfan Khan) fate. Based on Macbeth, the first of Bhardwaj’s acclaimed trilogy on Bard tragedies, there’s another twin in Maqbool hidden in plain sight. Look closely and the contours emerge. It’s the subplot involving Nimmi (Tabu), the sexually charged, younger mistress of don Abbaji (Pankaj Kapur) who seduces Maqbool into a web of murder, lust for power and greed and the angelic Sameera, Abbaji’s daughter. Nimmi and Sameera are unusual rivals, representing two entirely different forces but united in the end by the dire need to retain power for themselves. One of them will forge ahead Abbaji’s legacy. Theirs is an unlikely turf war, even as their respective lovers are daggers drawn in an ugly intra-gang war. As the two women, the younger and older, clad in ornate shararas dance to the tune of an underrated Gulzar gem, it’s difficult to conclude which Billo is the more ‘aankhon ki kameeni.’ This near-twin imagery reappears in Haider from 2014, the director’s supremely political take on Hamlet. It’s set in the heavily militarised Kashmir. Once again, Bhardwaj muse Tabu takes the lead, the sexuality in her latent but as savage as Nimmi of her younger years. With age, she has lost none of her sexual manipulation. Tabu plays Ghazala, Haider’s (Shahid Kapur) mother caught in the Oedipal world of latent desire. As if to balance her, Bhardwaj presents us with a beautiful Saira Banu version of Ophelia (Shraddha Kapoor). In the same film, notice the twin Salman Khan fans, Bhardwaj’s answer to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. In Haider, Bhardwaj embodies the best of Bard.

In Bhardwaj’s cinema, ‘trouble’ hunts in pairs, equal parts beauty and cruelty. Look at how he juxtaposes the beauty of Kashmir and its poetic imagery and Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s hope-giving prayers with violence and the human cost of war.

Unlike Haider, Kaminey’s twins owe more to the pulpy pleasures of Tarantino and Guy Ritchie than Shakespeare. (This is one of the few original screenplays Bhardwaj, who usually prefers adaptations, wrote). Still, the plot is Shakespearean. One brother lisps, the other stammers. This is a classic good versus bad trapped in a Pulp Fiction body. Also consider Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola, not the messy way it turned out but why it inspired Bhardwaj in the first place. The film’s inspiration lay in the Brecht play Mr Puntila and his Man Matti which is essentially a double act between the wealthy landlord and his chauffeur. As you can see, Bharadwaj, to use cricketing parlance, strikes his twos with a straight bat.

Of course, all given evidences suggest that Bhardwaj’s fascination for the twin may have its roots in Shakespeare. In previous interviews, Bhardwaj has revealed about his experience of mugging Shakespeare in school and how The Merchant of Venice haunted him as a child. In the same vein, he talks reverentially about Angoor, mentor Gulzar’s ode to The Comedy of Errors. In Angoor’s climax, as the mystery around the double twins is resolved, Gulzar’s camera lingers on, as a sort of fun in-joke, on a Bard-like figure nodding knowingly from a wall-mounted picture. Watching the Sanjeev Kumar and Deven Verma comedy, you feel like you are inside a Hrishikesh Mukherjee film. It’s not a typical Bollywood fare — not David Dhawan’s slapstick Judwaa, but something that taps the twin device for smart laughter.

There’s a Gulzar line the lyricist’s fans might be familiar with. “Don’t be upset with me. I am your judwaa,” Gulzar says, accompanying one online version of ‘Tujhse naraz nahin zindagi.’ He’s talking about having an imaginary conversation with ‘life.’ What does Gulzar mean by ‘judwaa’ here? We can only think out loud. It’s possible that Bhardwaj looks at Shakespeare from a passed-down version. He looks not at Shakespeare by Shakespeare so much as ‘Shakespeare as interpreted by Gulzar.’ The famous lyricist once quipped, “Vishal constructs his building on Shakespeare’s land. But the building belongs entirely to him. I don’t know why he calls it Shakespeare Tower.”

Would Gulzar Tower sound more apt?

(Shaikh Ayaz is a writer and journalist based in Mumbai)