Justice Ashok Bhushan, who read the judgement on behalf of the CJI, said the bench must find out the context in which the five judges had delivered the 1994 verdict.

Justice Ashok Bhushan, who read the judgement on behalf of the CJI, said the bench must find out the context in which the five judges had delivered the 1994 verdict.

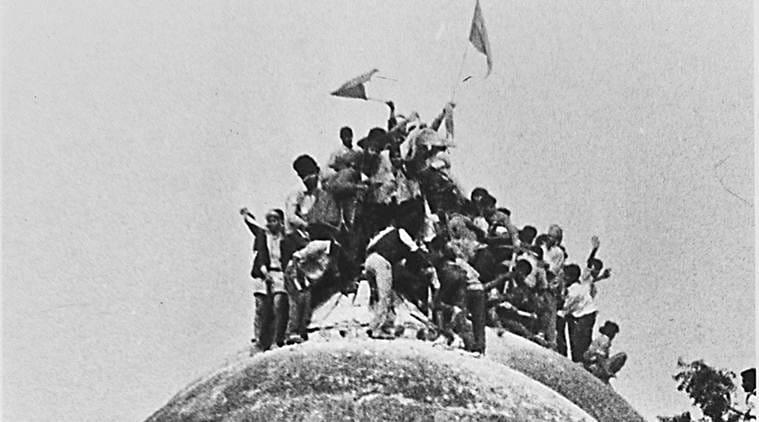

Setting the stage for resumption of hearing on the title suit over the disputed Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi site in Ayodhya, the Supreme Court, in a 2-1 verdict Thursday, rejected a plea to refer to a larger bench its 1994 ruling in which it observed that “a mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open”.

Appeals against the September 30, 2010 judgment of the Allahabad High Court that ordered a three-way division of the disputed 2.77 acres in Ayodhya, giving a third each to the Nirmohi Akhara, the Sunni Central Wakf Board of UP and Ramlalla Virajman, will now begin “in the week commencing 29th October”.

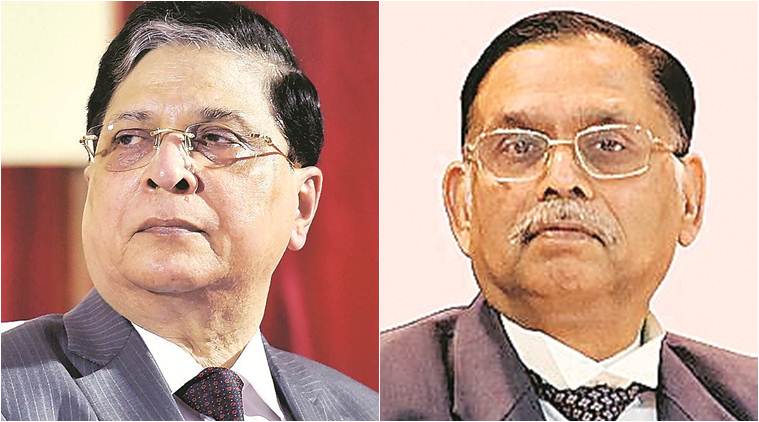

The bench of Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra, Justices Ashok Bhushan and S Abdul Nazeer split 2-1 in deciding not to refer to a larger bench its 1994 order on the Dr M Ismail Faruqui Etc. vs Union Of India And Others — Justice Bhushan, writing for self and the CJI, rejected the plea while Justice Nazeer gave a dissenting opinion, saying the Ismail Faruqui ruling should be reconsidered.

Under challenge was a statement in the Ismail Faruqui case judgment that a mosque was not an “essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam” and hence “its acquisition (by the State) is not prohibited by the provisions in the Constitution of India”. The petitioners had contended that earlier decisions in the Ayodhya case were influenced by this statement.

Rejecting this, the majority opinion said “we again make it clear that questionable observations made in Ismail Faruqui’s case… were made in context of land acquisition” and that “those observations were neither relevant for deciding the suits nor relevant for deciding these appeals”. The judges said that “the observation need not be read broadly to hold that a mosque can never be an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam”.

CJI Misra and Justice Bhushan underlined “in view of our foregoing discussions, we are of the considered opinion that no case has been made out to refer the Constitution Bench judgment of this Court in Ismail Faruqui case (supra) for reconsideration”.

They also turned down senior advocate Raju Ramachandran’s submission that appeals “against judgment dated 30.09.2010 of Allahabad High Court by which Four Original Suits, which were transferred by the High Court to itself, have been decided” be referred to a “Constitution Bench of Five Judges to reconsider the Constitution Bench judgment in Ismail Faruqui’s case”.

CJI Dipak Misra, Justice Ashok Bhushan

CJI Dipak Misra, Justice Ashok Bhushan

However, Justice Nazeer, in his dissenting opinion, said the conclusion in paragraph 82 of Ismail Faruqui order that “a mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open” has been “arrived at without undertaking comprehensive examination”.

“…it is clear that the questionable observations in Ismail Faruqui have certainly permeated the impugned judgment” (of the Allahabad High Court) and “it is clear… that the question as to whether a particular religious practice is an essential or integral part of the religion is a question which is to be considered by considering the doctrine, tenets and beliefs of the religion. It is also clear that the examination of what constitutes an essential practice requires detailed examination,” he said.

Referring to the Shirur Mutt case — in which it was observed that “what constitutes the essential part of a religion is primarily to be ascertained with reference to the doctrines of that religion itself” — Justice Nazeer said: “In my view, Ismail Faruqui needs to be brought in line with the authoritative pronouncements in Shirur Mutt.”

The Ismail Faruqui verdict came on a plea challenging the Constitutional validity of the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act-1993, under which 67.703 acres were acquired in the Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi complex.

In that case, the bench had observed that “under the Mahomedan Law applicable in India, title to a mosque can be lost by adverse possession… If that is the position in law, there can be no reason to hold that a mosque has a unique or special status, higher than that of the places of worship of other religions in secular India to make it immune from acquisition by exercise of the sovereign or prerogative power of the State. A mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open. Accordingly, its acquisition is not prohibited by the provisions in the Constitution of India”.

The question of the Ismail Faruqui judgment was brought up by senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan when the Supreme Court took up appeals against the Allahabad High Court verdict in the main title suit. He contended that to decide if any practice was an essential one, courts need to look into the tenets and examine them in detail. This, he said, had not been done before arriving at the finding in the Ismail Faruqui case.

The Uttar Pradesh government opposed this, saying the demand was never raised in the years since 1994 and the attempt now was only to “delay” and “avoid adjudication of a long-pending dispute”. The state also rejected the contention that courts below were influenced by the Ismail Faruqui judgment, saying the Allahabad High Court ruling had made it clear that its judgment was “not based upon Dr M Ismail Faruqui judgment”.

On these contentions, the CJI and Justice Bhushan said “one of the principal submission which was raised by the petitioners before the Constitution Bench (challenging the acquisition) was that a mosque cannot be acquired because of a special status in the Mohammedan Law”.

“The statement ‘a mosque is not essential part of the practice of religion’ is a statement which has been made by the Constitution Bench in specific context and reference. The context for making the above observation was claim of immunity of a mosque from acquisition. Whether every mosque is the essential part of the practice of religion of Islam, acquisition of which ipso facto may violate the rights under Articles 25 and 26, was the question which had cropped up for consideration before the Constitution Bench. Thus, the statement that a mosque is not an essential part of the practice of religion of Islam is in context of issue as to whether the mosque, which was acquired by Act, 1993 had immunity from acquisition,” the majority decision held.

The judges said “the sentence ‘a mosque is not essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and namaz(prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open’ is followed immediately by the next sentence that is ‘accordingly, its acquisition is not prohibited by the provisions in the Constitution of India’ which makes it amply clear that the above sentence was confined to the question of immunity from acquisition of a mosque which was canvassed before the Court. First sentence cannot be read divorced from the second sentence which immediately followed the first sentence”.

“What Court meant was that unless the place of offering of prayer has a particular significance so that any hindrance to worship may violate right under Articles 25 and 26, any hindrance to offering of prayer at any place shall not affect right under Articles 25 and 26,” the majority opinion stated.