A theatre in Perumbavoor, which is screening the Bengali film Bhaijaan Elo Re. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

A theatre in Perumbavoor, which is screening the Bengali film Bhaijaan Elo Re. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

39-year-old Mohammad Karim has poignant memories of the floods of 1988 that engulfed his home back in Nagaon district of Assam. Born into a family of traditional rice farmers, Karim, then just 9 years old, remembers gathering what little he could before fleeing the raging waters of the Brahmaputra that had begun to seep into his tiny home. He recalls joining his parents, sisters and scores of villagers to take refuge at the local railway station, considered safe as it is situated on a higher surface.

“Paani ka experience hai humein (We have experienced the effects of water),” he says in broken Hindi, smiling. The familiarity with floods and its trenchant consequences came in handy for Karim and his Assamese colleagues this month when they saw the waters of the Periyar rise swiftly around their homes and workplace in Perumbavoor town in Kerala. The town in Ernakulam district, considered the nerve center of migrant labour in Kerala hosting more than one lakh workers in its surroundings, has seen a steady outflow of labourers back to their home states after being ravaged by floods.

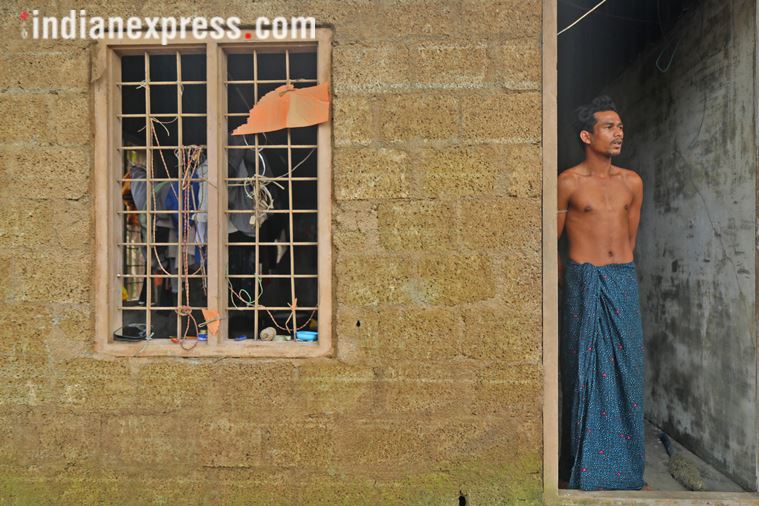

A worker from Assam. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

A worker from Assam. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

“We had close to 2600 migrant workers at a relief camp in the town alone. After water receded and trains began operating, we estimate a large number of them have gone back. A lot of factories and industries have been badly affected so there’s no work at the moment. It will take weeks to get back on track again,” says an officer at the local taluk office.

The road to Perumbavoor from Aluva, lined with plywood factories, brick kilns, stone-crushing factories and rice mills, bears the heaviest economic damage of the floods in the district. Many of these facilities, employing thousands of migrant labourers, are today shut, their machinery and equipments damaged beyond repair and its premises filled with layers of slush. Owners of small and medium-scale industries in these areas have to spend the next few weeks on concentrated cleaning and then running from pillar-to-post in search of government compensation and bank lending.

At a nearby authorized car dealership and workshop of a prominent firm, adjoining a paddy field, remnants of the floods can be seen on the asbestos roofs. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

At a nearby authorized car dealership and workshop of a prominent firm, adjoining a paddy field, remnants of the floods can be seen on the asbestos roofs. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

George, who runs a partnership of a factory that converts raw plastic trash into granules, says equipment worth Rs 15 lakhs and plastic material of at least 90 tonnes have been damaged. “We really don’t know where to start. We are a plastic scrap dealership. We don’t even know if we are eligible for government compensation. Kerala is not known for big businesses, but for small and medium-scale enterprises. If people like us are not protected, there will be big losses to the economy,” he says.

At a nearby authorized car dealership and workshop of a prominent firm, adjoining a paddy field, remnants of the floods can be seen on the asbestos roofs. The water that had risen more than 20 ft in height carried waste materials which remains deposited on the roof. “The water went over our roof. The entire workshop was under water,” says an employee, who did not wish to be identified.

Muzzamil Haque, also from Nagaon in Assam, is busy cleaning equipments. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Muzzamil Haque, also from Nagaon in Assam, is busy cleaning equipments. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

“We tried to shift as many cars as possible, but we still missed many. Thankfully, they are all insured,” he says. “The insurance companies are some of the biggest losers in this calamity. So many car owners being paid insurance will have never happened in Kerala before.” The shutdown of factories and dealerships like these mean massive job losses for the thousands of guest workers in Perumbavoor. Many of them opted to go home as soon as trains began operating, others moved to different towns in search of work.

Karim, who boarded a train to Kerala 17 years ago in search of a better life, commands a unit of 40 migrant workers, mostly Assamese, at a local factory in Perumbavoor that manufactures plywood and block-boards. When the flood-waters began to seep in, Karim instructed his junior colleagues to stack up all the important machinery in the factory to heights of at least 5 ft. Then, they trooped back to their humble dwellings, where at least 5-6 people shared a room, to pack whatever little they could into small bags.

For four days, Karim (in pic) and 40 other workers stayed on at the factory, where they were given food, water and other essential supplies by their employers. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

For four days, Karim (in pic) and 40 other workers stayed on at the factory, where they were given food, water and other essential supplies by their employers. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

“Water had risen to our necks. It was dark at night. All of us, hand in hand, walked together to reach the main road. The owner of the factory had arranged a car to take us to a nearby factory where water couldn’t reach. That’s how we escaped,” says Karim. For four days, Karim and 40 other workers stayed on at the factory, where they were given food, water and other essential supplies by their employers. As water receded, they came back to their factory to find it destroyed beyond imagination. They realised that there was no use stocking up machinery to 5 ft high when the waters submerged the very roof of the factory, that was at least 20 ft high. Three truck loads of timber wood had floated away. Dozens of machines, costing lakhs, sat in disrepair.

“We are staring at a loss of at least Rs 1 crore. We don’t know how to move ahead,” said Ashraf, the company manager. Nearly ten of Karim’s workers, belonging to Assam and Odisha, have left for their homes temporarily citing lack of work. Others, who couldn’t afford last-minute hefty train and flight tickets, have stayed back to help with the rebuilding and cleaning of the factory.

A plywood factory worker. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

A plywood factory worker. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

“Kaam nahi hai toh rukne ka mushkil hai. Ghar pe bhi log pareshan the (If there’s no work, it’s difficult to stay back. Our families at home are worried too),” says Karim. Ashraf, the factory manager, knows the price of ill-treating his workers. That’s why, instead of sending them to relief camps, he decided to take care of them at another facility.

“Avaru poyal, Perumbavoor theernu (If they all get up and leave, Perumbavoor will be finished),” he says. “They are neat workers. Some of them have gone home, but we expect them to return soon.” At another nearby facility, that manufactures machinery for plywood factories, Muzzamil Haque, also from Nagaon in Assam, is busy cleaning equipments. Haque had flight tickets booked on August 18 to go home for Bakrid but as the Kochi airport suspended operations after its runway was flooded, Haque had to change his itinerary.

A migrant worker in Perumbavoor. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

A migrant worker in Perumbavoor. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

“Ghar jane ka man tha, but kaise jaata. Flight cancel ho gaya, abhi september mein jaunga (I wanted to go home, but how do I go if the flight got cancelled. Now, I will go in September),” he says.

Haque, who has mastered conversing in Malayalam having worked in Kerala for the last 8 years, attests to having good relations with his employers, who ferried him and the others to safety when the waters rose. “I have never seen water rise like this so fast. Before going to bed, water was not even in the front porch. But when I woke up the next morning, there was water all around my bed,” he says.

Migrant workers at a Begali cinema show. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Migrant workers at a Begali cinema show. (Express photo by Nirmal Harindran)

Subsequently, his employer arranged vehicles for him and three others at the factory to move to a safer place. “We ate at the relief camps and slept at the rooms provided to us,” he says. Two kilometres away, the Lucky cinema theatre, in the middle of Perumbavoor town, is showing a Bengali cinema, ‘Bhaijaan Elo Re’. Inside the asbestos-roofed theatre, just about 60-odd people, mostly Bengalis and Odia workers, are seated, leaving over 400 seats empty. In the darkness of the theatre, many of them light their beedis and cigarettes, lending an acrid smell to the place.

Outside, Kamal Sarkar, a native of Nadia in West Bengal, stares long and hard at the film posters, wondering whether to buy a ticket. At the end, he chooses not to waste his money at a time when there’s little work. Sarkar missed the floods by a whisker as he went home before the waters rose. But back at home, he says he was extremely uncomfortable seeing visuals on TV of people struggling to survive in the floodwaters.

“Khub kharab legechilo. Amader lok toh, onek koshto hoyechilo (I felt really bad. These are our people, it was very painful to see them like this),” said Sarkar in Bangla. “Kerala is a very good place, I like it better than even Kolkata,” he says, smiling, before walking off.