The two Travelling Gate Keepers repeat the stop-run-stop-run routine at 34 unmanned level crossings. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

The two Travelling Gate Keepers repeat the stop-run-stop-run routine at 34 unmanned level crossings. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

We never expected a bullet train, but I wish we had a train that ran faster than a bicycle,” says G Ramamurthi, who is travelling from Pattukkottai in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur district to Kandanur-Puduvayal, 66 km away.

His comparison isn’t off the mark: the Pattukkottai-Karaikudi EMU train takes nearly five hours to travel a distance of 74 km, during which it stops at 34 unmanned level crossings and five railway stations.

At each of these level crossings, the already crawling train lets out a loud horn and screeches to a halt. A gatekeeper from the front engine room hops off, closes the gate and the train begins crawling. Soon after it has crossed the gate, the train halts again. This time, a gatekeeper from the engine room at the rear end hops off, opens the gates, hops back on and the train moves. A journey on this train is to know what it is to turn time on its head.

Yet, this train of three coaches and two engine rooms is what Pattukkottai is most excited about.

The train, which runs twice a week, on Mondays and Thursdays, is the first the town has seen in 16 years. Pattukottai, better known in Tamil Nadu as the native town of former president R Venkataraman, has had a railway line dating back to 1894, when it was built by the South Indian Railway Company as part of the Mayavaram-Muthupettai segment. However, train services on this route were stopped in 2002 for a gauge conversion project. Sixteen years later, on July 1 this year, railway operations finally began on the new metre gauge Pattukkottai-Karaikudi segment.

Officials say the train, brought from the Trichy division, is an “experimental service for three months”, during which the Railways will decide whether to continue the service, change its timings or cancel it altogether.

1.30 pm: Boys from a nearby government school run along the platform, cheering and waving, as the train leaves the Pattukkottai station. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

1.30 pm: Boys from a nearby government school run along the platform, cheering and waving, as the train leaves the Pattukkottai station. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

N Jayaraman, in his late 70s and leader of the Pattukottai Railway Passengers’ Welfare Association, is at the station today. A retired bank manager, Jayaraman says it would have been helpful if the train ran in the mornings and evenings. “Even if it is slow, many school students and office goers could have used it. But the train leaves at 1.30 pm and reaches Karaikudi around 5-5.30 pm. It’s of no use to anyone,” he says, dismissively.

“Some one lakh people travel between Pattukkottai and Karaikudi every day. Many depend on service buses and some use their own vehicles. Why can’t the Railways appoint guards at all these level crossings and increase the speed and number of services?” he adds.

A senior railway official at Karaikudi station says the Railways will need a staff strength of at least 115 if they have to avoid stopping at every unmanned level crossing. “We have only 15 people on the rolls along this stretch. Some stations have no station masters. Each gate will need at least three gate keepers, which is about 100 people in all for the gates. But we can save at least two hours if we have manned level crossings,” he says.

Ramamurthi, the passenger on his way to Kandanur-Puduvayal, cherishes his memories of the Boat Mail Express, which ran between Madras and Rameswaram via Pattukkottai for decades, before the line was shut. “It took us less than three hours to get to Karaikudi from here. And in 2018, we take five hours,” he says.

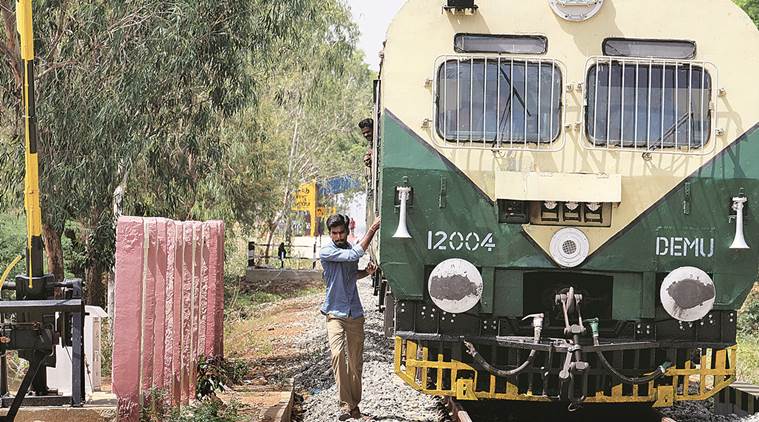

2 pm: One of the two ‘Travelling Gate Keepers’ on the train opens the gates at an unmanned level crossing and runs back to board the train. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

2 pm: One of the two ‘Travelling Gate Keepers’ on the train opens the gates at an unmanned level crossing and runs back to board the train. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

At 1.25 pm, with five minutes left for the train to leave, some 20-odd boys in school uniforms stop their game of hide-and-seek mid-way and hop off the train. They are from the nearby government school and have half an hour left for classes to begin, so had turned up to see the train.

At 1.30 pm, an hour after its arrival from Karaikudi, the guards and engine drivers board the train and a horn announces its departure from Pattukkottai railway station. The schoolboys run along, cheering and waving, and stop only when the platform ends. Even after the train has left the station, the boys continue to whistle, a send-off gesture for the train that will return only two days later.

The first level crossing after Pattukkottai is manned, one of only three such gates en-route. But within three minutes, the engine driver pulls the break — at the second level crossing. The train stops a few yards before the gate and a man in his 20s jumps out and runs to the gate room by the road.

He is the ‘Travelling Gate Keeper’ and it takes him about three minutes to close the two gates on either side of the tracks, using a ‘manual gate-lifting barrier’. By now, the train begins moving and he runs back to board the engine room. Just as it crosses the level crossing, the train stops again. This time, the second Travelling Gate Keeper, who sits in the engine room at the rear end, jumps out, and opens the gates.

This stop-run-stop-run routine is repeated at three more crossings between Pattukkottai and the next station, Ottankadu, the only station on the stretch that still hands out ‘card tickets’ to passengers. It takes 40 minutes for the train to cover this 12-km distance.

“There is a level crossing every 10 minutes and the train stops for at least five minutes at each of these. Isn’t this slower than a man walking?” asks Ramamurthi, adding that the train has on an average speed of 20-30 kmph. “But I am in no hurry,” he smiles.

Like on most days, there are hardly 30-50 passengers on board the train against its total seating capacity of 216. Each of the passengers has her own reasons for taking the train.

3.30 pm: Like on most days, there are hardly 30-50 passengers on board the train against its total seating capacity of 216. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

3.30 pm: Like on most days, there are hardly 30-50 passengers on board the train against its total seating capacity of 216. (Express photo by Arun Janardhanan)

Vijaya, in her early 80s, says she is going to her daughter’s house in Periyakottai, 62 km from Pattukkottai, from where they will go to the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court to attend a family dispute. “Her husband abandoned her and her two children. She is fighting a property dispute case now,” Vijaya says, sitting by the window.

Saradha Chandrakumar from Pattukkottai, and on her way to Madurai, is one of the two mothers on board the train who have made cradles fashioned out of saris. “We will stay at a relative’s house at Karaikudi tonight. We have taken the train because there are two children with us. They will cry for a cradle,” she says. “We have a wedding in Madurai tomorrow. I also have to go to Aravind Eye Hospital,” she adds, detailing her travel plan.

Christina Swamy, another passenger who is travelling to Karaikudi, says the delay in gauge conversion cost an entire generation of children in Pattukkottai access to bigger towns and cities such as Thanjavur and Chennai. “A lot of our children went to Karaikudi Agricultural University and Thanjavur Medical College… all that was closer to us. Also, petitioners getting to the High Court (Madurai Bench), patients travelling to the eye hospitals in Madurai and school- and college-going students who study outside Pattukottai would take the train. But when the rail line was closed for close to two decades, these places became out of bounds,” says Swamy.

She adds that she chose the train as she was “not in a hurry” to reach her sister’s house in Karaikudi.

For all these passengers who are “in no hurry”, the ticket fare also plays a role in them preferring the rail route — while a bus ride from Pattukkottai to Karaikudi costs Rs 70 or 90, a train ticket is only Rs 20.

S Pugazhenthi, one of the two ticket examiners on board the train, is done with his work in the first 20 minutes. Pugazhenthi says that unlike on other trains, on this, they have been told not to fine passengers without tickets.

Instead, they carry ticket receipts — anyone can buy a ticket on board.

As Pugazhenthi settles down for lunch around 2 pm, his colleague V Karthikeyan stands at the door, waving at students of the Peravurani government school who cheer loudly. “They are so curious because the narrow gauge train on this stretch stopped even before they were born,” smiles Karthikeyan.

Past Peravurani, Ayingudi and Aranthangi stations, the train stops at Valaramanikkam around 3.30 pm. Two more stations and over a dozen level crossings are left before the final destination. Four passengers, a man selling tender coconuts and a tea vendor are the only people on the platform. As the train leaves Valaramanikkam after a 10-minute break, thunder clouds can be seen on the horizon.

The train is now approaching Kandanur-Puduvayal and Ramamurthy prepares to get off. “The train stops for only 1 minute here. It’s a halt station. But it was a full-fledged station during the British period,” he says, hopping off the train.

Around 5.10 pm, when the train finally pulls into the Karaikudi station, there are only six passengers left on board. Ticket examiners Karthikeyan and Pugazhenthi rush to catch another train to get home to Trichy, about 80 km away. The Pattukottai-Karaikudi EMU will be shifted to a yard, where the engine and its three coaches will rest for another three days before their journey back to Pattukkottai.