Mulk hit screens on August 3.

Mulk hit screens on August 3.

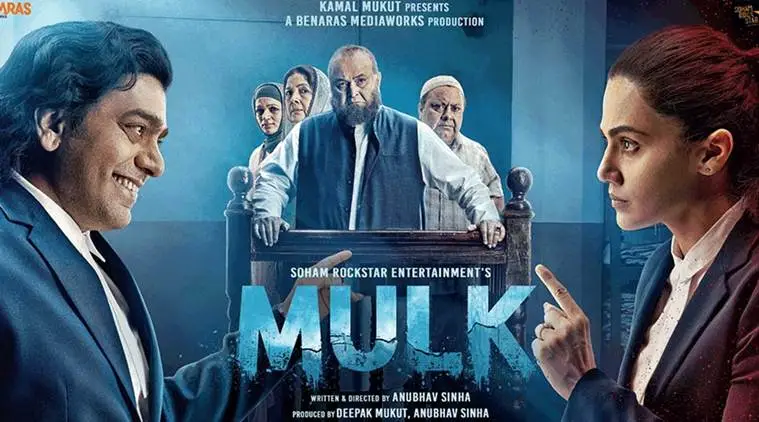

Inadvertently, or otherwise, Twitter has been responsible for awakening the conscience of many Bollywood filmmakers. One of them is Anubhav Sinha. With his latest cri de coeur, the maker of Mulk joins the political-filmmaker ranks of Anurag Kashyap, Sudhir Mishra, Dibakar Banerjee and Hansal Mehta to name a few whose films reflect a social consciousness while remaining not only decidedly within the Bollywood framework but also unashamedly aspiring for a larger fanbase. So far, they have been successful in reaching out. These filmmakers, it appears, are very much in touch with ground reality. Provoked by divisive national politics, the prejudices against minorities and the questions of terrorism and justice, Sinha decided to get out of Twitter to make something more substantial and long-lasting. Like Kashyap (and Saeed Mirza before them all), Sinha is an “angry” filmmaker. In interviews promoting Mulk’s release on August 3, Sinha, whose filmography otherwise features duds like Ra.One and Cash, has admitted that the decision to make Mulk was partly in response to the personal attacks he has been facing for his political views on social media. Starring Rishi Kapoor, Taapsee Pannu, Rajat Kapoor, Neena Gupta, Manoj Pahwa and Prateik Babbar, Mulk addresses the meaning of patriotism and religious polarisation among other political and communal issues that have haunted the national headlines in recent years.

“Not every question has an answer,” Sinha has reasoned, declaring that at the very least, if a filmmaker has raised “the question” it is enough.

“I have said in this movie what I have felt,” Sinha conceded. Watching the film amid a packed audience on Sunday night, this writer discovered that the filmmaker has said plenty on a subject he is clearly passionate about. Like Kashyap’s Mukkabaaz, Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan and Shubhashish Bhutiani’s Mukti Bhawan, Mulk is set in Banaras. If you thought only right-wing politicians are capable of appropriating Banaras, think again. Bollywood has also, of late, woken up to the infinite political and social possibilities of the holy city, a citadel of Hindu India but also a secular bastion that has long sheltered the minority Muslims in a tradition that reflects religious harmony at its best.

Murad Ali Mohammed is a retired advocate and a much-respected member of this minority faction in a Hindu neighbourhood. Bearded (minus the moustache, believed to be preached by Prophet Mohammed himself and followed by Islamic sects including Hanafis and Deobandis) and always clad in a kurta and vest, Rishi Kapoor’s Murad gallantly defies Tarek Fateh’s definition of “a Muslim with a beard without moustache is tell-tale sign of an Islamist who has the potential of becoming a jihadi terrorist.” His name is Murad and he’s not a terrorist, as it turns out. (Incidentally, Santosh Anand, the public prosecutor played by Ashutosh Rana, uses the My Name is Khan reference in the court proceedings to comic effect. He may be an Islamophobe but the bigger one happens to be the self-hating Muslim cop Danish played by Rajat Kapoor). Murad is a modern Muslim who feels customs should move with the times. “When the dargah was built,” he explains to his nephew Shahid (Babbar), while stuck in a traffic jam, “there was space in the city. Now, there’s none. Religious practices should change with time.” Indeed, a common complain among non-Muslims is why the faithfuls, in maddening crowds no less reminiscent of Occupy Wall Street, spill over on to the streets for Friday prayers. Can they not pray in the clean confines of their home? Can the loudspeaker go easy on the prayer call?

Meanwhile, in Banaras, Murad lives with his family, wife (Neena Gupta), brother Bilal (Manoj Pahwa), his wife and a nephew and niece. His friends are Hindus and he seems to enjoy a peaceful community life. However, when Shahid (Babbar) falls into the trap of radical Islam and as news of his involvement in a deadly bomb blast unspools, Murad’s “home” disintegrates. The Hindu neighbours won’t trust him anymore and an environment of hostility – “us versus them” as Aarti (Pannu), Murad’s lawyer and daughter-in-law puts it in an argument in the court – engulfs the otherwise tranquil town.

Sinha uses this opportunity to set much of Mulk in court and it’s here that the film makes its sharpest political and religious barbs. As the innocent Bilal stands accused in the court, Murad is faced with the most important question that afflicts this film and perhaps the average Indian Muslim today – “How do I prove my love for the country?” In a candid heart-to-heart with Aarti, Murad recounts that when he got married, his wife used to test his loyalty by asking him to prove his love to her. How do you prove your love to someone, or something, that you already love. You express love by loving. It’s understood, isn’t it, asks a baffled Murad and that’s exactly what the film seeks to investigate. Through that artifice, Sinha puts forth several burning questions that we have been grappling with as a nation every time religious tension escalates.

“Go to Pakistan,” a troublemaker inscribes outside Murad’s home. The Ali family didn’t make that choice in 1947, why should they now, defends Aarti. Despite his family’s pleas to move out of India, Murad decides to stay back and fight for his dignity and honour and in the process, through the judiciary as a “voice of reason” Sinha gets to train his gun on his many pet peeves. Predictably with such heavy-loaded films, Mulk gets, at some point, too taken up by the issues it wants to represent. There’s a check-all-the-boxes urgency to it. Has the beef issue been addressed? Check. Do we have a Hindu religious bigot for a lawyer? Check. Are Muslims, with their large families, breeding ground for terrorism? Check. Good Muslim versus Bad Muslim? Check. Scenes like Aarti going in for divine blessings at the roadside temple as the Muslim family waits on their big day at the court is too simple-minded and predictable and does not hold up to the otherwise blunt note that Sinha manages to strike in other moments.

Both in India and globally, post 9/11, the image of Muslims has taken a sharp dip. While Hollywood doesn’t care enough about Islamophobia – and why should it, so long as there is a token terrorist to supply the villainy – Bollywood refrains from the Muslim issue. But then, to expect a commercial medium to do the task best suited to the State is somewhat foolish.

What emerges from Mulk is that, in India at least, being a Muslim is not a curiosity. The court, preceded over by Kumud Mishra, gently reprimands the prosecutor over his ignorance about the Muslim contribution to the nation. And at the same time, Mishra also directs Murad and the community to keep an eye on the Jihadist Islam. While no prizes for guessing where Sinha’s sympathies lay, Mulk is a balanced portrayal of a community urgently in need of reform and revival.

Cinema can’t bring this much-needed revival. But ordinary Indians like Murad, Aarti, Santosh Anand and more significantly, Shahid, can.

(Shaikh Ayaz is a writer and journalist based in Mumbai)