Music in discord: Alokananda Dasgupta at her workstation in Mumbai. (Source: Craig Boehman)

Music in discord: Alokananda Dasgupta at her workstation in Mumbai. (Source: Craig Boehman)

In the opening sequence of the first episode of Sacred Games, there is a Tarantino-esque shootout, where one of the villains, Malcolm (Luke Kenny), guns down people in a restaurant. The robust yet mellow riffs of the cello, violin and clarinet add to the savagery of the scene. The lilting waltz is “a sort of requiem” for the Vikramaditya Motwane and Anurag Kashyap-directed Netflix series. “There is an element of melancholy in the piece, which I had originally intended to put in Sartaj’s (Khan) life. But it was very interesting to club it with a violent scene. I think the incongruity works really well,” says Alokananda Dasgupta, composer of the soundtrack, which includes four original songs.

Director Motwane was worried that the piece was “too lilting and lullaby like”. But Dasgupta, 34, says she had the liberty to go against what the director had originally told her. “Vikram (Motwane), unlike a lot of filmmakers, treats background score as one of the writers (of the script). He gives it as much importance as his own editing even though he worries too much about the score. So, convincing him that this will work was also fun,” says Dasgupta.

The best scores are undistinguishable from the visuals they accompany, creating emotional responses that shape our perception of a film/show. Dasgupta’s score has the same delicate balance of dynamics. You can hear it in the whispers of the intense love song Dhuan dhuan, for instance, paired with violin harmonies and light rhythms, written by Dasgupta’s older sister and lyricist Rajeshwari, plays in the scene when Ganesh Gaitonde’s (Siddiqui’s) love interest, Kukoo (Kubbra Sait), dies in a shootout. There is also Saiyyaan, a dubstep piece during a riot at a club. “The first scene has no expression of love, yet I could feel the sorrow and pain, the tension in it. It was organic and intuitive. It is his love story. It’s a random piece that comes from silence. The dubstep piece would usually sound ridiculous during a riot and there it is, making sense,” says Dasgupta.

Traditional pieces on the sitar, or bells paired with quirky electronic instrumentation, accompany scenes that describe Gaitonde’s past. “Vikram’s advice to me was that I should treat Sartaj’s scenes as more of the journey of the crime, and Gaitonde’s more as fables where you can do weird things musically,” says Dasgupta. One of the most striking pieces is the heaving and haunting title track, that plays as the credits roll, interspersed with archival sounds and images. Motwane’s brief was to extract the core of the series musically into a few seconds. “For me, it was like being asked to do precis writing in school. Vikram and I bounced ideas through reference tracks. We did a lot of trial and error,” says Dasgupta, who has used live instrumentation besides electronic music for the score.

Dasgupta was brought in on the project much before the series got shot. “There was a lag between me knowing that I had to compose and the episodes coming to me. Later, it all just fell apart, I just went with the flow and created by instinct,” says Dasgupta, who chose to stick to bass sounds of cello, her favourite instrument, for the large part.

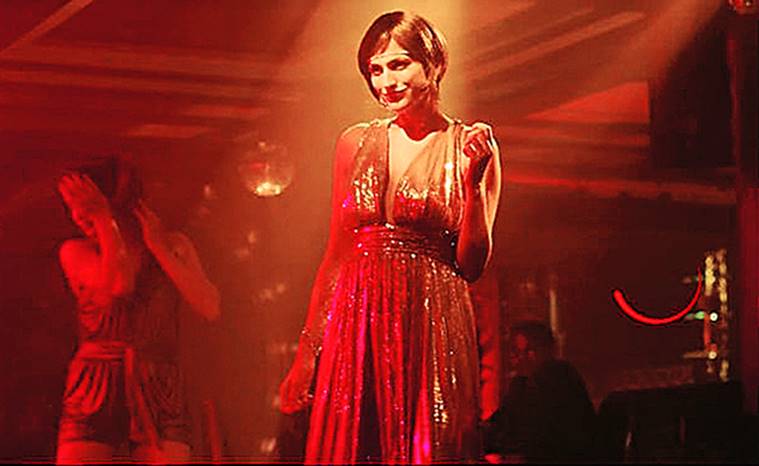

A scene from Sacred Games where Kukoo (Kubbra Sait) dances to Saiyyan. (Source: Netflix)

A scene from Sacred Games where Kukoo (Kubbra Sait) dances to Saiyyan. (Source: Netflix)

According to Varun Grover, one of the writers of Sacred Games, whenever content is created for a global market, the tendency is to use the sitar or sounds that denote India. “What’s interesting about Alokananda’s music is that she has not exoticised it through the use of Indian instruments and yet kept it very Indian with the use of strings. Also, while writing, I was keen that we use a lot of film songs from the time, for example, in the background or on the radio. But we couldn’t because of budget constraints and permissions and that made me quite disappointed. But Alokananda’s original pieces didn’t allow me to miss those songs. There is that organic weaving of the whole thing with the narrative,” says Grover. As for Dasgupta, she was worried about striking a balance. “It couldn’t be overpowering. It had to stay at the back, only appear when required, and had to be quirky as well,” says Mumbai-based Dasgupta.

She grew up in Kolkata learning classical piano and Odissi. Her father, poet and filmmaker Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s love for the instrument led to the two sisters training formally under the aegis of Royal College of Music, while her mother’s passion for dance gave them the grounding in rhythm and movement. The LPs and vinyls playing at home, almost all the time, nuanced their understanding of sound. So, while they heard symphonies and concertos by Bach and Beethoven since they were five, Begum Akhtar, Rabindrasangeet, Simon and Garfunkel, The Carpenters and The Beatles filtered in through the gramophone, shaping Dasgupta’s musical sensibilities.

But public performances were nerve-wracking and made Dasgupta very anxious. “So much so that I decided to not perform. I just couldn’t take the pressure. In Kolkata, while learning the piano, I was expected to perform. But I realised that I liked to analyse and appreciate music more. So, I found my own niche. I was happy composing behind locked doors,” says Dasgupta, who, after studying English literature at St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata, went to Toronto to study composition and musicology at York University. “Eventually, I realised that I didn’t want to be a performer and could do other things with music,” she says.

In Canada, she heard Amit Trivedi’s compositions in Aamir, and was moved by the banjo-and-tabla qawwali Ha Raham. Back in Kolkata in 2008, she called Trivedi to ask if she could work with him. He agreed and Dasgupta moved to Mumbai the next year as Trivedi’s assistant. While she found insight into Trivedi’s work through his project Dev D (2009), which she heard extensively, she finally assisted him on Udaan (2010), No One Killed Jessica (2011) and Chillar Party (2011). She notated his compositions and learnt how to work with music through software. Even though being a Bollywood composer was never the idea she had nurtured, Dasgupta liked the “in-between-ness” she could be a part of. “This was music that was intelligent, insightful and in Bollywood,” she says. And wanting to compose scores was always on her mind. “You are never introduced to scores, no one talks about them. I naturally gravitated towards them. I have been interested in scoring from a young age. At the back of my mind, I liked the idea of scoring for visuals. I just wanted to come to Mumbai, experiment and see if I can carve out a place for myself. With unique composers like Amit (Trivedi) and Sneha Khanwalkar (in the industry), I realised that there could be space for my kind of music too,” says Dasgupta.

Alokananda Dasgupta’s first Bollywood project Udaan.

Alokananda Dasgupta’s first Bollywood project Udaan.

Udaan was the turning point. “I couldn’t identify myself in mainstream Bollywood or in Mumbai as such. But Udaan and Vikram’s sensibilities had a positive effect on me,” says Dasgupta, who did commercial advertising work for Motwane. She composed jingles for Pepsi, Apple and Fortis Hospitals, among others, besides Neeraj Ghaywan’s short film Juice, Sujay Dahake’s Marathi film Shala (2011)and her filmmaker father’s films Anwar ka Ajab Kissa (2013) and The Bait (2016).

Ajay Bahl’s BA Pass (2013) happened to her before Motwane offered her the Rajkumar Rao-starrer Trapped (2016), a film where sound played a significant role because of the few dialogues and the character having no one to talk to. “Here, there was no scope for flamboyance. We needed music that stemmed from the soundscape of the film — the character trying to bang utensils, shaking the geyser, cutting the grill with the blade — so, these sounds became characters in the narrative. Then came the idea of creating a score with the sounds to complete the whole effect of claustrophobia,” says Dasgupta. The construction noise around her house would trouble her no end but she decided to record and use it for Trapped.

With Sacred Games, there was the comfort of having worked with Motwane previously, knowing his language, likes and dislikes. “And his silence — he doesn’t say much. He tries to explain things to the point. There is no hierarchy — we work together, throwing and bouncing ideas off each other. He never shuts anything out and tells me why something isn’t working,” says Dasgupta, who was directed by Motwane even for Kashyap’s sections.

Dasgupta’s focused approach does hint at a long innings in a volatile industry. It helps that the mindset about background scores are changing. “Score is no longer something that’s an appendage. People now want a good soundtrack. They aren’t in just for a few songs,” says Dasgupta, who is in talks with directors after the success of Sacred Games, and has received appreciation from composer AR Rahman. Her forthcoming project is her father’s film The Flight (Urojahaj).