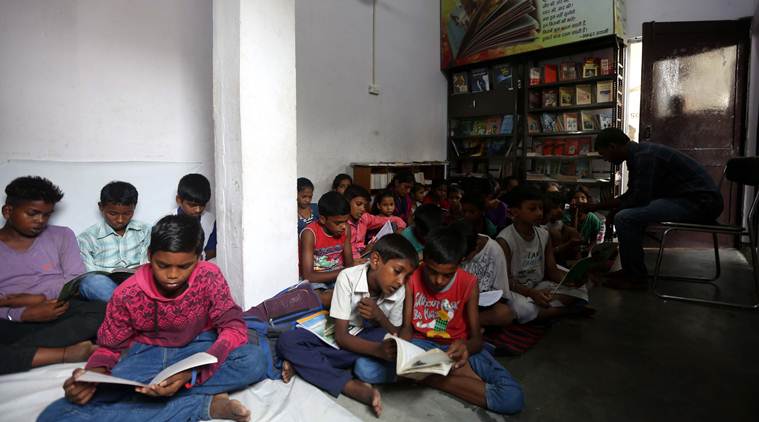

At Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya, Jamalpur. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

At Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya, Jamalpur. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

THEY CALL it “shiksha ka inquilab”, or the education revolution. On the faded walls, with bits of plaster peeling off, are posters of Bhagat Singh and Maxim Gorky. There’s a board outside that reads: “Behtar zindagi ka raasta behtar kitaabon se hokar jaata hai (The road to a good life passes through good books).”

This is Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya, a one-room library established nine months ago by workers and daily-wage labourers employed at factories in the industrial heart of Ludhiana, the hub of cycle-makers, auto-parts manufacturers and textile units.

With over 500 books, in Hindi and Punjabi, it’s a 25-sq-yd island of change for children from the Lower Income Group (LIG) flats and slums of Jeewan Nagar, Rajiv Gandhi Colony, Dhandhari and Jamalpur, mostly populated by migrant workers and their families, and where clean drinking water and toilets are part of a daily struggle.

Set up by the Karkhana Mazdoor Union, which took the lead in collecting nearly Rs 3 lakh last year to purchase LIG flat No 498 in December 2017, with two fans and a worn rug on the floor, the library was built on individual contributions ranging from Rs 100 to Rs 5,000.

Kids at the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya- a library established by the laborers at LIG flats at Jamalpur in Ludhiana.Express Photo by Gurmeet Singh

Kids at the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya- a library established by the laborers at LIG flats at Jamalpur in Ludhiana.Express Photo by Gurmeet Singh

“A majority of the factory workers and daily-wage labourers who contributed have not studied beyond Class 8. But they want to inculcate the reading habit in their children. Most of them earn less than Rs 10,000 a month,” says Lakhwinder Singh, who heads the union and manages the library.

“The idea remained a dream for years because there was no space. This small flat was bought from contributions… sometimes it gets difficult to accommodate everyone but that’s all we could afford. Once the flat was purchased, we started buying books, we got some through donations,” he says.

There are no reading charges at the library — just Rs 50 for an annual card that will let readers take books home, two at a time. “The charge is to ensure that they are responsible and return the books on time. We also issue cards. For these children, a library card is a prized possession, they preserve it like a trophy,” says Singh.

On a recent rainy afternoon, a group of children were scampering towards the library, jumping over puddles of water. “We really like coming here. We don’t have any story books at home. They are costly and our parents cannot afford them… my father is a barber,” says Akash Ram, a Class 8 student at the B R Ambedkar Public School in Jeewan Nagar.

There are no reading charges at the library — just Rs 50 for an annual card that will let readers take books home, two at a time. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

There are no reading charges at the library — just Rs 50 for an annual card that will let readers take books home, two at a time. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

“We want our children to read and have access to books, which we can’t afford. That’s what Shaheed Bhagat Singh wanted, too. He wanted the light of knowledge to reach the poor so that they can fight for their rights. This is what we call shiksha ka inquilab,” says Gurcharan Singh, 44, a security guard who was among those who contributed to the library.

“Most of the parents here are so poor that they make their children drop out of school after Class V or Class VI. They start working as child labourers. We are encouraging them to come here and at least read some books. We organise a free tuition class, too, which is attended by 25-30 children every evening,” says Krishan Kumar, 24, who helps Lakhwinder run the library.

Among the several contributors are Deepak Kumar, an electrician who has studied till Class 10; Teju Prasad, a helper at a factory who has studied till Class 8; and, Ramesh Chand, who works in a cycle factory and has studied till Class 10.

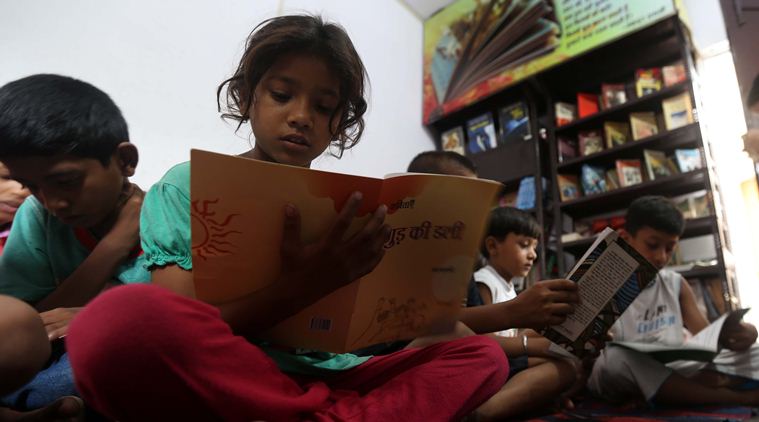

Most of the parents here are so poor that they make their children drop out of school after Class V or Class VI. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

Most of the parents here are so poor that they make their children drop out of school after Class V or Class VI. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

“With our meagre salaries, it is difficult to run our homes but this had to be done. We want our children to know about the dignity of labour, instead of feeling ashamed. While writing an essay in school, they should not merely copy what is written in their books, that ‘my father is a doctor or an engineer’. They should have the courage to write the truth and say ‘my father is a labourer’. For that, we need to give them knowledge,” says Deepak Kumar, who has two sons studying in Class 7 and Class 10.

Inside the library, the books are neatly arranged in two racks, and on a table — most of the books are stories for children.

“We don’t have access to basic amenities like clean water, roads, toilets, etc., but that doesn’t mean we cannot think of providing knowledge to our children. We even encourage the women at home to come here and read. Opening this library has given us so much happiness and a sense of achievement because we were not able to complete our education,” says Teju Prasad.

Rajinder Kaur, principal at the nearest government high school, in Sherpur Kalan, says the library has come as a boon for her students.

Inside the library, the books are neatly arranged in two racks, and on a table — most of the books are stories for children. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

Inside the library, the books are neatly arranged in two racks, and on a table — most of the books are stories for children. (Photo: Gurmeet Singh)

“Most of the children in our school are from Jamalpur and the slum colonies nearby. Till Class 8, their education is free of cost but students in Class 9 and 10 have to pay a small fee… Rs 30 per month for girls and Rs 67 for boys. Some of the parents are so poor that they cannot afford even this,” she says.

According to Ludhiana education officials, there is a fund of Rs 10,000 per year for each government school to buy books for extra reading. “But the fund is irregular. Besides, there is no allocation for the construction of library rooms. Since most government schools don’t have enough classrooms, library rooms are never a priority,” says a senior official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

At the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Pustakalaya, none of this matters now.

“My father sells bhel puri in the day and works at a factory in the evening to earn extra for us. We are proud of him,” says Kareena, 13-year-old Class 6 student, looking up with a smile.