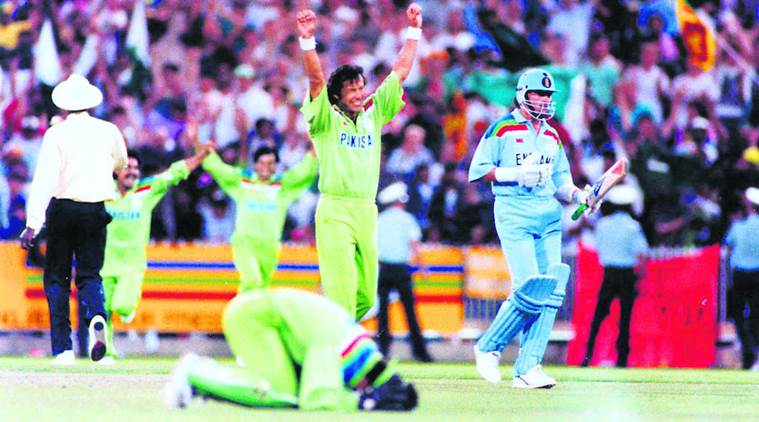

Crowning Glory: The Pakistan of early 90s would ideally need a team of ringmasters, but Imran Khan not only managed it single-handedly, he won the 1992 World Cup with it. (Express Archive Photo)

Crowning Glory: The Pakistan of early 90s would ideally need a team of ringmasters, but Imran Khan not only managed it single-handedly, he won the 1992 World Cup with it. (Express Archive Photo)

Running a nation is not the same as leading a cricket team, but as Pakistan’s sole World Cup-winning captain, Imran Khan was known to be his own man who almost always had his way. He played with the opposition’s mind, and captivated his own teammates’. But in a country largely run by the generals, it remains to be seen how the former all-rounder will fare

He has been called Taliban Khan, ‘Im the Dim’ and even a ‘cocaine-sniffing serial-fornicator narcissist’. But the one tag that has got Imran Khan extra hot under that stiff white collar of his long-flowing kurta has been ‘Army stooge’. At a pre-poll Lahore rally, adding extra bass to that famous baritone, he had thundered: “Imran Khan kisi ka putla nahi ho sakta”.

With reports aplenty of rampant rigging and charges rife of the deep state batting for Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), speculation about Imran being operated by remote control from Rawalpindi (the Army Headquarters) haven’t stopped. Imran might have the crown, but he doesn’t have the halo that had emerged around him as he lifted that sparkling crystal trophy after the 1992 World Cup final at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The undermining of the PTI victory is a throwback to Imran’s early days in cricket — the Shakoor Rana-Khizer Hayat era of Pakistan umpires wearing the love of the home team on the sleeves of those ill-fitted white coats — when dodgy LBWs would invariably undermine his wickets.

Now, the world waits to see if Imran — the man who tirelessly advocated and later pioneered the appointment of neutral umpires in cricket — has it in him, at 65, to reform Pakistan politics like he changed his country’s cricket. That’s a dream he has been trying to sell, it’s a narrative he wanted his voters to believe in. Like in 1992 when he transformed his underachieving young team of underdogs into world beaters, he has promised a Naya Pakistan.

Unlike cricket writers, hardened political pundits, witnesses to several false dawns in Pakistan, don’t romanticise Imran. They credit his inevitable elevation to the worldwide mass acceptability of the personality cult. Even that comes with a rider. Unlike elsewhere, Imran can’t expect unequivocal power in a country where the Army has traditionally outranked the executive. No democratically elected prime minister has finished his term in a country that has been ruled by generals off and on for decades. Still, the presence of the self-proclaimed “most famous Pakistani ever” in the power huddle of the world’s most strategically important nation cannot be underplayed.

The vast majority of the cricketing world, especially those uninitiated to Pakistan’s many layered political milieu, can’t imagine a subservient Imran, pulled by strings. How can the master puppeteer become a puppet? It’s a question they never tire of discussing in Pakistan’s cricket circles — roughly the entire nation.

It’s a rhetorical question of the faithful rather than an conspiratorial inquiry of the doubters.

Even 26 years after his retirement, the cricketing lexicon refers to every powerful, independent thinking, border-line autocratic captain who leads from the front as an Imran Khan. Many have been compared to him, but none have filled Imran’s shoes. Arjuna Ranatunga, Steve Waugh, Sourav Ganguly, Virat Kohli, or even Mike Brearley, can’t match Imran’s body of work, his influence, his aura or even his mere presence on the field.

Common sense says that the burden of shepherding a nation is much heavier than running a cricket team, but sports gives a truer insight into the mind of a leader. On the central square of the stadium, there are no walls to hide behind or carpets that can conceal problems. With the clock ticking and countless eyes of entire nations trained on them, captains take important calls. Imran relished these situations, he enjoyed the spotlight and the pressure; for he rarely got it wrong.

Unlike in cricket, where he inherited the team leadership unequivocally, Imran’s political emergence hadn’t looked mainstream till this election. Often heard hectoring away or sniping sullenly at the Islamabad establishment for whom he reserved his scorn with as much rabid fervour as his other target — the Americans, Imran had spent the last two decades in distant FATA of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The Pakistan electorate hadn’t immediately warmed up to him, as his natural charisma seemed tethered to fringe voices from the country’s western border where the army held undisputed sway. If only running a country was as simple as running in fast, leaping away from the stumps and bowling that big in-swinger that approached the stumps like a truck.

While children in Pakistan grow up listening to tales of Imran’s eye to spot talent, his knack to spot a rival’s weakness often remains untold. And also his slyness to get under his rival’s skin by clever optics — a quality that career diplomats and seasoned politicians spend a life-time perfecting.

Before their ‘must win’ game against Australia in the 1992 World Cup, he broke a tradition. Instead of the Pakistan Green, he turned up for the toss wearing a T-shirt that had a growling Tiger on the prowl. He had anticipated two things — the interviewer Ian Chappell asking him about the tiger and the Aussies listening to his well-rehearsed answers in their dressing room.

Years later, he relishes repeating the story that unfolded as he had foreseen. Google “Tiger + toss + Imran” and watch Imran the actor. Here’s how the transcript goes.

Ian Chappell (pointing to the tiger on the T-shirt): I thought you were the Lion of Lahore, what’s this?

Imran: That’s what I have been telling Allan (Border), I want my team to play like a cornered tiger. You know that’s when it is most dangerous.

And boy, they were dangerous, cornered or otherwise.

The Pakistan of 90s, would ideally need a team of ringmasters but Imran managed it single-handedly. Maybe, only Snow White would have an inkling about Imran’s job at hand. There was Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, Dopey, Doc, Bashful and Sneezy plus a few mavericks, match-fixers and Miandad — that was Imran’s brood. So when allegations were made that Imran was aligning with “reptiles” — a not too subtle hint at a televangelist with charges of hate crime against him joining PTI — those close to him didn’t see it as a kiss of death. They knew Imran had played all his cricket in a snake pit.

As the captain of the most unpredictable cricket team, Imran knew the trick to turn overawed rookies into fearless match-winners. Imran would hand-hold them on the path to irreverence. Aaqib Javed, just 16, got an unusual advice, as he was coming to terms with his shaking legs, sweaty palms on his first sighting of Vivian Richards. “Maaro b*****d ko bouncer,” Imran told him. Aaqib still has those words ringing in his ears. “After that I began to think like a lion,” he said.

While addressing large crowds of mostly young males, Imran has regularly called Donald Trump boring, predictable and materialistic. He is a harsh critic of NATO’s war on terror. Imran loves “Us vs Them” situations. His advice to Pakistan isn’t very different to the one he gave Aaquib.

Imran has a plan, but the switch from managing a squad of 20 to a country of nearly 200 million is a giant leap. His political philosophy has changed with time but with power coming to him, the real Imran is now expected to step forward.

In his seminal book, The Unquiet Ones, Osman Samiuddin has drawn a beautiful parallel between Pakistan’s cricket captains and its political leaders. “Pakistan has experience with such leadership types, men who hijack the voice of a country rather than necessarily speak for a nation… Kardar and Imran are, in this sense, stroked from the same old, dried paintbrush as Jinnah and the Bhuttos.”

But then, he has been shoutng his guts out: “Imran Khan kisi ka putla nahi ho sakta.”