The paper reflects many significant social and economic realities and takes into account the 64th round of the National Sample Survey.

The paper reflects many significant social and economic realities and takes into account the 64th round of the National Sample Survey.

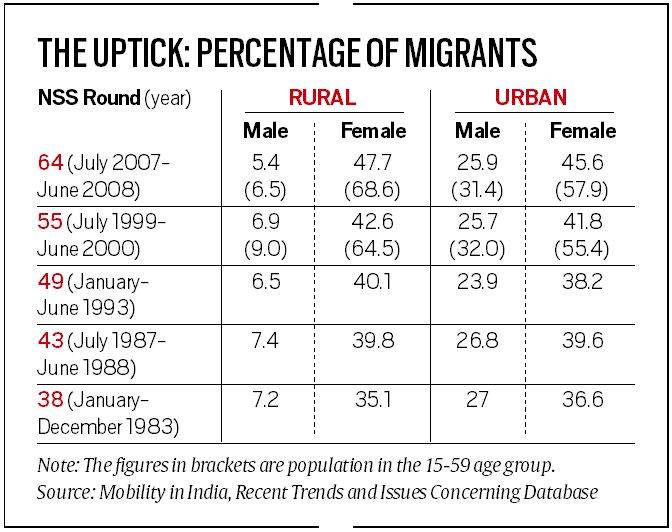

The number and rate of women migrating within India are increasing; it has been on the rise over the past three decades in rural and urban areas; at the same time, the ratio of adult male migrants to adult population has decreased.

These are among the findings in a new paper, which indicates that Indian women are travelling more within the country — primarily for economic reasons and better employment — often alone and at a higher rate than men.

The findings “undermine the thesis of massive migration to the existing urban centres leading to their demographic growth and of labour market integration in the country” says a paper by Distinguished Fellow at the Research and Information System for Developing Countries, Prof Amitabh Kundu, titled Mobility in India, Recent Trends and Issues Concerning Database.

The paper reflects many significant social and economic realities and takes into account the 64th round of the National Sample Survey (NSS), the most recent for which migration data is available, as well as figures from the 2011 Census and the National Health and Family Survey IV.

In 1993 (49th NSS round), female migration was 38.2% in urban areas — that is 38.2% of urban women were migrants. In 2008 (64th NSS round), this went up to 45.6%. For men, it increased from 23.9% to 25.9% over the same period. For men in the age group of 15-59 years, however, this percentage has come down, from 32% to 31%.

The paper cites “evidence in the NSS to suggest that migration of women has gone up over the past three decades both in rural and urban areas. Marriage mobility of women is determined by socio-cultural factors that change slowly over time and hence the spurt in their migration rate must be attributed to economic factors.”

“There are other macro-level indicators that also confirm the above proposition. National Health and Family Survey IV, for example, shows that the percentage of women aged 20-24 married before the age of 18 has gone down from 47 in 2005-06 to 27 only in 2015-16. Furthermore, women aged 15-19 already mothers or pregnant at the time of the survey has become half from the alarming figure of 16 per cent in 2005-06,” the paper says.

“It would, therefore, be no surprise if women work participation and their mobility for economic reasons show a happy rising trend. This conclusion can also be derived easily from the 2011 Census data on migration.”

Speaking to The Indian Express, Kundu said, “Women migration for economic reasons has gone up as revealed through NSS data, which classifies migrants by reasons of mobility. The urban labour market is offering employment opportunities to women though at the bottom of the economic ladder. A large percentage of them work as domestic help whose demand has gone up with the increase in work participation rate among middle and upper-class women.”

“Also, single male migration driven by poverty and other push factors has gone down. There is an increase in family migration at higher income and skill levels, which improves the gender ratio among the migrants,” said Kundu, who was a member of the National Statistical Commission from 2006 to 2008.

Dr Pronab Sen, until recently, Chairman of the National Statistical Commission, said: “A lot of the migration has been for marriage. Earlier, women migrating in the same district would not be counted as migration, now, the migration also means women marrying across districts, which is an indicator of the skewed gender-ratio, especially in cities, so it shows up as more women migrants.”

Economist, Prof Jayati Ghosh at Jawaharlal Nehru University who has also closely studied the phenomenon says: “There has been in the past three, certainly two decades, a leap in the number of single women travelling for work and migrating and taking up any odd job. I have seen in Bengal and Andhra Pradesh, women migrating in groups even if for short periods, at a time of deep agrarian distress, women going in search of work as men were not getting any kind of employment. Earlier, women mostly travelled with their husbands for work.”

In his work analysing several aspects of internal migration over four decades, Kundu is concerned about issues in reporting of migrants, under-reporting in 2001, change in classification of towns in 2011 and the Economic Survey of 2017 treating railway journeys undertaken as data for migration. This, he says, has led to a belief that there has been accelerated migration, a conclusion he contends, the data does not support.

Urbanisation has been welcomed as it correlates strongly with most indicators of development including per capita income, industrial value added and level of amenities despite problems like congestion, pollution and a high percentage of slum population. But the circumstances that push segments of a population to migrate are also important when evaluating its pros and cons.

Recently, there has been concern over not including work done by women in the Indian economy and their low participation. According to a report by McKinsey in June, just about 25 per cent of India’s workforce is female. A 10 per cent increase to that, estimates the report, could “add $770 billion to the country’s Gross Domestic Product in the next seven years”.