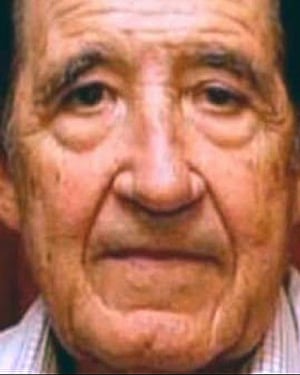

The first trial in Spain over thousands of suspected cases of babies stolen from their mothers during the Franco era has opened in Madrid as an 85-year-old former doctor appeared in the dock.

About 50 demonstrators protested outside the court as Eduardo Vela, who worked as a gynaecologist at the now-defunct San Ramón clinic in Madrid, arrived in court. Some carried signs saying “Justice!” and “Human rights for stolen babies”.

Vela is accused of taking Inés Madrigal, now 49, from her biological mother in 1969, and giving her to another woman he falsely certified as her birth mother.

Prosecutors are seeking an 11-year jail term for falsifying official documents, illegal adoption, unlawful detention and certifying a non-existent birth.

In a dark and often overlooked chapter of General Francisco Franco’s 1939-75 dictatorship, the newborns of some leftwing opponents of the regime, or unmarried or poor couples, were removed from their mothers and adopted. The practice was later expanded.

New mothers were frequently told their babies had died suddenly after birth and the hospital had taken care of their burials, when in fact they were given or sold to another family.

Madrigal, a railway worker who heads the Murcia branch of the SOS Stolen Babies association, said she did not expect Vela would provide answers about her origins or apologise. But she hoped his two-day trial would lead to the reopening of other “stolen babies” cases.

“A mother can never forget her son,” she told reporters outside the court. “Mothers want to tell their children that they did not abandon them … but above all they want to know that they are well.”

Franco came to power after Spain’s 1936-39 civil war pitting leftwing Republicans against conservative Nationalists loyal to the general, who was seeking to purge Spain of Marxist influence.

Beginning in the 1950s, the practice of taking babies away from families opposed to the regime was expanded to poor families and babies born to unmarried mothers.

The guiding principle was that the child would be better off raised by an affluent, conservative and devout Roman Catholic family.

The system – which allegedly involved a vast network of doctors, nurses, nuns and priests – outlived Franco’s death in 1975 and carried on as an illegal baby trafficking network until 1987 when a new law regulating adoption was introduced.

Campaigners estimate that tens of thousands of babies may have been stolen from their parents.

The scandal has similarities with what happened in Argentina during the 1976-83 military dictatorship, when about 500 newborns were taken from their mothers and given to couples that supported the regime.

Campaigners say at least 2,000 other complaints for similar cases have been filed but up until now none has gone to trial in a country still coming to terms with the dictator’s legacy.

Cases have been shelved due to a lack of evidence or because the statute of limitations had passed.

In 2013, an 87-year-old nun who worked with Vela was questioned in court but died before she could be tried.

Vela was interviewed briefly by police after a magazine in 1982 published interviews with several women who claimed they had had their babies taken after giving birth at San Ramón, but the case was dropped.

He told investigators in 2013 that as the director of the clinic he often signed papers without reading them, and has claimed that he only helped women who wanted to put their children up for adoption and never pressured any mother to do so.

Interviewed by the BBC in 2011, Vela grabbed a metal crucifix and said: “I have always acted in his name. Always for the good of the children and to protect the mothers.”

Carmen Lorente, who came from the southern city of Seville to protest outside the court, said she was told her baby son suffocated in the womb in 1979 even though she recalls hearing him cry after giving birth.

“It is a very important day for all those who are affected and for all mothers. Because a precedent is created by this man sitting in the dock,” she said.