The “Irish giant”, a centrepiece of the Hunterian anatomical museum in London, could be released to allow the remains to be given a respectful burial after more than two centuries on display.

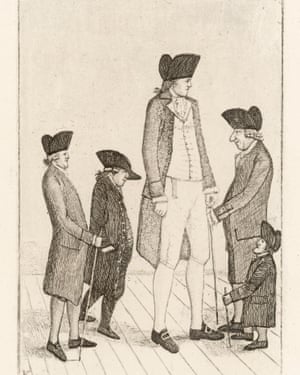

The skeleton is that of Charles Byrne, an 18th-century man who had a genetic form of gigantism that caused him to grow to more than 2.31 metres (7ft 7in) tall.

Before dying, Byrne asked his friends to ensure he was buried at sea in a lead coffin to prevent gravediggers exhuming his remains and selling them to the medical establishment. Byrne’s plan was thwarted, but in recent years the museum has come under increasing pressure to honour the Irishman’s final wishes.

Now the museum, which has just closed for three years for refurbishment, says it is considering doing so.

In a statement, a Royal College of Surgeons spokesman said: “The Hunterian Museum will be closed until 2021 and Charles Byrne’s skeleton is not currently on display. The Board of Trustees of the Hunterian Collection will be discussing the matter during the period of closure of the museum.”

Byrne was born in 1761 and left his hometown in County Derry in his teens to find fame and fortune. After travelling through northern England as a “curiosity act” he became a London celebrity, inspiring a pantomime called the Giant’s Causeway, and moved into an apartment in Charing Cross.

However, Byrne soon entered a downward spiral. When his life savings were stolen in a pub he began drinking heavily, and subsequently contracted tuberculosis and died at the age of just 22. A newspaper of the time noted that “a whole tribe of surgeons put in a claim for the poor departed Irishman surrounding his house just as harpooners would an enormous whale”.

In keeping with Byrne’s wishes, his friends arranged for a sea burial at Margate. However, possibly after bribing an undertaker to switch the corpse, the pioneering Scottish surgeon and anatomist John Hunter acquired Byrne’s remains.

Four years later the skeleton appeared in Hunter’s private collection, and it has remained on public display for much of the two centuries since then at the Hunterian Museum, run by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Until now, the museum has rejected calls for the skeleton to be taken off display, arguing that it was of important “educational and research value”. It could, for instance, allow the identification of shared genes between Byrne and living individuals with the same condition, known as acromegalic gigantism.

However, Thomas Muinzer, a law lecturer at Stirling who has researched the case, said: “You or I could donate our bodies to medical research, but that does not presuppose that one of us could be put on display as a novelty or curiosity object. There’s no reasonable case for keeping the body on display … burial seems the humane, sensible and ethical thing to do.”

Carla Valentine, technical curator of the Pathology Museum at Queen Mary University, London, agrees. “Obviously most specimens in museums like ours and the Hunterian are from a pre-consent culture,” she said. “But with Charles Byrne, the difference is that he made it so explicitly clear that this is not what he wanted. We really have to honour that.”

The renovation period would be a good opportunity to remove the skeleton without leaving a gaping hole in the exhibition, she added: “Now that it’s out there that they’re considering this, I think it will be difficult to go back from that.”

If the skeleton were released, some campaigners have suggested it should be returned to Northern Ireland to be buried near Byrne’s home village of Drummullan.