Thirty years ago this month Jaguar won Le Mans for the first time since the 1950s, and the very next day one of the spectators, now somewhat hungover, reported for his first day working for Autocar magazine and, indeed, as a motoring journalist.

Three decades later and to no-one’s greater astonishment than mine, I’m still here, albeit in the guise of senior contributing writer, rather than assistant deputy envelope licker under manager, or whatever it was back then.

It is no exaggeration to say Autocar saved me. I left school without sufficient qualifications to get me to a university, after which I got fired from more jobs in just four years than most people have jobs in their lifetimes. Bond dealer, commodity broker, trainee lawyer, ice cream salesman (yes, really) – you name it, I lost it.

For a while it looked like Autocar would go the same way. Both my immediate boss on the road test desk and the big scary editor soon realised I’d not been so much as economical with the truth in my application as flagrantly dishonest. But I was desperate. I could drive but only a bit, but could not write. At all.

You can tell how precarious was my position at Autocar by looking at the so-called ‘flannel panel’ list of editorial staff in magazines published after I joined in mid-June 1988. I have copies from late August in which my name still fails to appear because, as said editor helpfully explained, "I’d only have to take it out again".

But most of us have one person back to whom the start of whatever small success we may have enjoyed can be traced and mine is Mel Nichols. Many of you will remember Mel as one of Car magazine’s greatest editors and it was his contributions to Car in the 1970s that helped spark my love of cars.

But by 1988 he was the Editorial Director of Haymarket Publishing – Autocar’s owners then and now – and instead of just telling me my writing was rubbish like everyone else, he ventured to explain why it was rubbish and what might be done to make it less rubbish. One of the finest writers this industry has known, he saw a small shoot of something peering out of the cesspit of my prose and for reasons known only to him, chose to nurture it.

Then two of his fellow Australians pitched in. First was Peter Robinson, who became Autocar’s European Editor late in 1988 and was and remains the greatest journalist ever to shine his talents upon the car industry, and then came Steve Cropley, who was the other significant inspiration in my childhood when he succeeded Nichols at the helm of Car.

Once, when I was about 13, I was in London burger bar with my father when a red Ferrari 308GTB pulled up outside. From its interior Cropley emerged and walked into the restaurant. I wouldn’t have been more starstruck if it had been the entire cast of Charlie’s Angels, and no more likely to follow my father’s advice to go and introduce myself. When I first told him this story I can remember Steve looking about as aghast as a large Australian can look, and I smile at the thought he’ll be doing it all over again, right about now.

Robbo taught me how to be the best journalist I could be, while Cropley was my staunchest supporter throughout my time on the staff. Every time some other mag came sniffing, Cropley would take it upon himself to explain to those who wore suits why I needed to be persuaded to stay. And thanks to him, stay I did, leaving only when it became clear they weren’t about to hand the editor’s chair to someone entirely unqualified for the job.

But I left with a deal that Autocar would hold my hand by providing me with some work as I tried to establish myself as a freelance journalist. And 22 years later, it seems it still is.

I have many memories of the last 30 years but rather too many that can’t be published while I still require a living from this business. But I can tell you James May got sacked because he chose to take the rap alone for a stunt involving many conspirators, none more guilty than me; and one of my early freelance editing jobs was to massacre Chris Harris’s fledgling road tests. Remarkably, both remain friends to this day.

I’ve had only one proper accident (so far at least, which I think is reasonable in more than a million test miles), when I destroyed the UK’s first Lancia Integrale Evolution one icy January day in 1992, cracked some ribs and earned some concussion while discovering I wasn’t Juha Kankunnen after all. At the time the only amusing aspect of the episode was that when the story came full circle back to me it held that I’d parked the car on its roof in a field. In fact it came to rest right side up, on the road, its roof literally the only panel of the entire car to remain unmolested.

Short of crashing, the other experience I’d choose not to repeat from my years on the staff was driving 2326 miles in 24 hours on (European) public roads in a 1.6-litre, 90bhp Ford Mondeo crewed only by me and Steve Sutcliffe. Looking at those stats nearly a quarter of a century later it seems almost unimaginable, and my chief memory is the sense of relief at the end knowing I’d never have to do anything quite so stupid ever again.

Autocar also facilitated the realisation of a childhood dream, namely to get my name into the Guinness Book of Records. My first ever freelance job came in around 1990 when the good book rang Autocar looking for someone to update its motoring pages. I just happened to pick up the telephone, and for the princely sum of £50 per year became its motoring editor.

But there were no records that looked remotely within grasp and for some strange purist reason, I didn’t want to set a new record. I wanted to break an existing one. So I hatched a plan and told no-one about it.

I got permission for a new record – the fastest lap of a UK circuit – to be set. At the time it was probably Keke Rosberg’s 160mph qualifying lap at Silverstone for the 1985 British Grand Prix. But all the road testers had gone faster than that in normal street machines around the Millbrook bowl. It felt like cheating but it was definitely a lap. So I offered my boss, Howard Lees, the chance to the set the record, which he duly did at 171mph in a Ferrari Testarossa in 1991.

I then broke the standard in its quicker, more stable 512TR replacement the following year at 174mph. Job done. It is possible therefore that I also hold the record for being the only person ever to write their own record into the Guinness Book of Records.

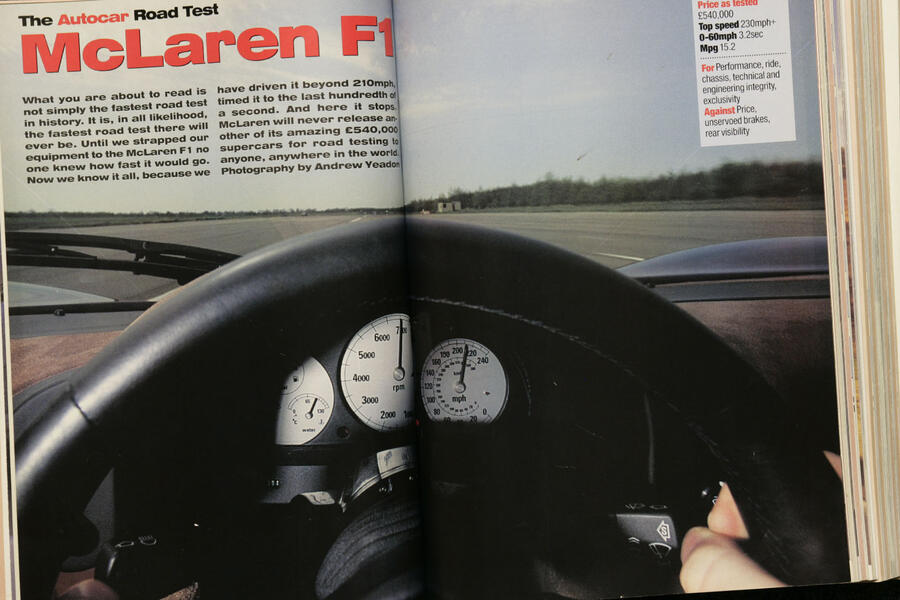

I went faster in 1994 – 211mph while running figures for the only full road test of the McLaren F1 – and have been quicker still in a Bugatti Veyron Supersport (an unverified 217mph), but being part of the crew that landed the F1 test was probably my proudest moment from my years as road test editor, and among the most bittersweet of memories too, coming as it did the day after Ayrton Senna was killed at Imola.

After I left probably the most bizarre incident came in Sicily on the launch of the Ferrari California in 2009. I was doing those oversteer shots for the camera of Stan Papior (the only bloke to have started at Autocar before me and to still be there) when I noticed a man and a small boy standing at one of turnaround points. I thought he’d come to admire my skills. I was soon disabused of this notion when next time round the boy had gone and been replaced by a shotgun by his side.

Why I continued I’ll never know – I expect I thought he was out shooting rabbits – but I was still relieved to notice a few minutes later that he’d gone. Relieved that is, until a shot rang out somewhere over my head. My most vivid memory is trying to turn the convertible Ferrari around while ducking as much of my 6ft 4in frame below the window line as I could. I drove back and informed Stan that it was probably time to change location.

As for how the cars have changed, there’s an entire other story in that so I’ll mention now only that in the back in 1988 we’d tested just one car, a Lamborghini Countach, that had cracked the five-second barrier for the 0-60mph sprint. Today there are Volkswagen Golfs and Ford Focuses that can obliterate that time.

But it is the people I’ve worked with over the years who’ll live on in the memory long after those of the cars have faded. It’s not possible to maintain the same connection when you work alone in a shed in Wales as when on the staff, but through a long succession of editors and a large number of testers, I’ve never felt less than part of the Autocar crew, none more so than today when find myself writing more for the title than at any time since I went freelance.

If I had a religious bone in my body, I would call myself blessed. For the truth is that while I’ve lived in a number of different places over the last 30 years, Autocar has always been my home. I hope it will remain so for a little while yet.

Read more