In the 1660s the Paston family of Norfolk commissioned a Flemish artist to record the treasure they had heaped up in their mansion – a glittering hoard including a globe showing their travels and the far-flung sources of their porcelain and crystal, as well as precious shells and ostrich eggs fashioned into goblets of gold and silver.

After years of research, the painting is going on display again in Norwich with as many of their treasures as could be traced and borrowed back, but the research – which included identifying and recording for the first time the sheet music being held by the pale little girl in the picture – has also revealed how the painting foretold the downfall of one of the wealthiest families in England.

“The exhibition tells both a very Norfolk story and a genuinely international one,” said Francesca Vanke, the curator at Norwich Castle museum. “The first clues to the story are in this painting. They open up a world we never knew existed, for which evidence is scattered worldwide.”

The painting was given to the museum in the 1930s by the descendant of one of the buyers from the Pastons’ 18th-century “garage sales”, and was regarded then as a historical curiosity rather than a major work of art. However, its eerie atmosphere and teeming detail have mesmerised generations of visitors.

After years of international research, in a partnership between the museum and the Yale Center for British Art, many but not all of its secrets have been decoded.

The exhibition includes Paston family possessions, and many of the surviving objects in the painting, brought together for the first time in 300 years from museums and private collections in Europe and the US.

The Paston family is beloved by historians for a unique set of medieval letters tracing their family and financial affairs in vivid detail. By the mid-17th century they were rich, powerful landowners. When they commissioned the swaggering boast of their wealth and culture, around 1663, the painting was also a vanitas, with the hour glass, the ticking clock, the flowers and fruit which will decay and rot, the reminders that life is fleeting and death inexorable.

The Pastons could not have guessed how true this was for them: there would be many deaths in childhood including the little girl in the painting, and within two generations the family would be overwhelmed by debt, the treasures scattered in a series of sales, and their huge house, Oxnead Hall, abandoned and then sold, and later almost entirely demolished in the 18th century.

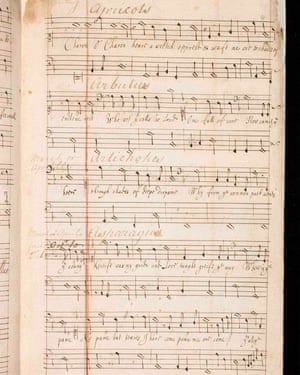

Jonathan Wainwright, a professor of music at the University of York, has pored over enlargements and identified the song of the little girl as an appropriately doom-laden piece by the Scottish composer Robert Ramsey, “Charon, O Charon, heare a wretch opprest”, written in 1530. Only one manuscript survives in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, but the music in her hand was so meticulously painted that he could read it. The first recording of the song, commissioned by the Castle museum from the Royal College of Music, will be played during the exhibition.

Wainwright has also traced a second musical reference, though in the painting the tiny book held by the satyr on the golden stem of the shell cup was too minute even for his eyes. However, on the real cup, coming on loan from the Prinsenhof museum in Delft, he could read the words of a popular 16th-century round song – again dealing with death – “Je prens en gré la dure mort”.

The art historians believe the painting was either commissioned by Sir William Paston, an epic collector and traveller who got as far as Cairo, Constantinople and Jerusalem, or by his son Robert to mark William’s death in 1663.

Robert was a passionate amateur scientist – believed to account for the unusual number of different expensive pigments used in the painting – who practised alchemy for years but failed to turn base metal into much-needed gold.

He died aged 52, overwhelmed by debt partly caused by the ruinous cost of lavish hospitality including a party for King Charles in 1671, after a life scarred by gout, scurvy and depression.

His son William would inherit massive debts, begin disposing of the treasures far earlier than previously thought – the research turned up a sale receipt from 1709 – and finally the mansion itself. He was bankrupt by 1732, with debts equivalent to £16m today.

The little girl was Robert’s daughter, and died in childhood. The handsome young African boy has not been identified, but so many of the details have proved to be accurate depictions of real objects, that the researchers think he must also have been a real person, possibly living in the Paston household.

The artist is one of the unresolved mysteries, but the research has turned up another painting by the same hand, coming on loan from a New York collector, which includes the same grey parrot. Another painting from the family collection has also just been traced in a private collection by the art historian Simon Swynfen Jervis, a former director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, who recognised family coats of arms when an acquaintance moved home and hung the picture in a brighter room. It will be on display in the exhibition for the first time, but the discovery was so recent it came too late to include it in the catalogue.

• The Paston Treasure: Riches and Rarities of the Known World, Norwich Castle Museum, 23 June to 23 September