A cloud of white blocks leaps from a plinth, hanging in the air like an explosion in a sugar cube factory. Nearby, a great spiral of ribbons swirls across a model landscape, like a whirlwind of noodles caught among the trees. A host of other curious creations fills the basement gallery of Japan House, a new cultural centre on Kensington High Street, west London, from teetering nests of wooden sticks to sheets of scrunched up paper, and what looks like a floppy silver pancake resting on a glass cube.

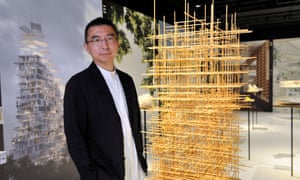

These are the dreamy visions of Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, who approaches the design of his buildings more like a conceptual artist searching for new forms – or a scavenger foraging through a skip.

“Trash can be very liberating,” he says, standing next to a row of plinths that display pieces of torn cardboard, a washing-up scourer and a pile of potato crisps, each adorned with a tiny model figure to suggest their transformation into something of an architectural scale. “It makes us more relaxed and open-minded, and helps us to forget what we know. Everything can be a possible architectural space.”

Fujimoto, now 46, shot to international prominence in 2013 following his beguiling Serpentine Gallery pavilion. It was one of the most ambitious creations in the 18-year programme, standing as an amorphous white structure of slender steel rods that formed a climbing frame of steps and seats, hovering like a pixelated apparition in the park. It did exactly what the annual commission does best: highlight a little-known foreign architect, give them a platform to distil the essence of their work and propel them to global recognition.

“It was like having a free pass to anyone,” says Fujimoto with a broad grin. “It gave me confidence. But more than that, it changed my approach to my work and gave me a new perception of how a building could be landscape, furniture and enclosure at once.”

The seeds of his pavilion design – formed over an intense month of self-reflection and experimentation, during which he says his proposals were rejected by the gallery directors as “too Fujimoto” or “not Fujimoto enough” – are revealed in the exhibition. You can see how loops of folded paper and carved polystyrene evolve into a pixelated mass, part-terraced landscape, part-cave. It is the solid form of what would become the hollow frame, where inside, outside, floor and roof would meld in a shape-shifting blur.

Five years on, these seeds have germinated into a global portfolio of projects run by an office of 35 people in Tokyo and 20 in Paris, working on everything from an apartment tower in Montpellier to a 1.2km-long shopping mall for an undisclosed country in the Middle East. The former will be an astonishing sight, erupting with enormous cantilevered balconies in all directions. The latter would have been a gargantuan stack of colonnades rising to pointed spires – the Serpentine frame on Islamic arch-infused steroids – but it was cancelled “when the king changed his mind”. A big boat-shaped block of flats with a forest on the roof is being planned for Paris, while the aforementioned silvery pancake will soon emerge above a music hall in a park in Budapest, where concerts will take place in a glass bubble surrounded by forest on all sides.

“I really like the feeling of being in a forest,” says Fujimoto, who grew up in rural Hokkaido on the edge of woodland. “It’s an open field but you feel protected, being surrounded by many small pieces. And it inspires curiosity: the fact you can’t see everything inspires you to walk to discover more.”

A forest of books was the idea behind his library for Musashino Art University in Tokyo, built in 2010, where one endless bookshelf spirals around in concentric circles, perforated by doorways and bridges. “Of course, the librarian wanted it to be organised and systematic,” he says, “but the other role of a library is to create space where students can meander and happen upon things they weren’t looking for.” His solution synthesises order and happenstance, with book categories arranged radially around a central counter, while the paths that cut across his spiral allow students to drift and discover.

Something of an outsider architect, Fujimoto has never worked for another practice, which perhaps explains his firmly original approach. “I was scared of being rejected,” he says. “And if I had gone to work for another architect, they might have overpowered me because I was so easily influenced.”

He arrived at the University of Tokyo intending to study physics, but was so flummoxed by what he found that he switched to architecture, which he studied for just two and half years before graduating in 1994, with no interest in continuing to do a master’s degree. “I then had a nice couple of years in Tokyo,” he recalls, “getting up around noon most days and thinking idly about architecture, sometimes going to look at buildings, but mostly just being on my own, thinking and making drawings.”

Like so many architects, he began his career with a helping parental hand, designing a ward for the psychiatric hospital that his father ran in Hokkaido. Rather than following the conventional rooms-off-corridors approach, he arranged the patients’ rooms opening into a shared living space and introduced privacy to a place that had always been configured around having no place to hide.

Fujimoto’s interest in balancing the needs of privacy and openness became an obsession. His first domestic projects are almost surrealist exercises in how inside can be separated from out with anything but a simple wall. Instead, he layers, nests and stacks spaces to blur the transition from public to private. House N, built in 2008 in the town of Oita, Japan, is “a box within a box within a box” like a Russian doll, each perforated enclosure adding another layer of privacy as you move from the street to the centre of the home. House NA, built in 2011 in Tokyo, is the closest thing to a glass and steel treehouse, where 20 little glass-walled rooms are suspended in a steel frame, “allowing you to hop between the levels like a monkey or a bird in a tree”. Perhaps tired of being performing monkeys for architectural tourists, the residents now keep their curtains firmly closed.

His love of toying with the limits of exposure and privacy reaches its peak in one of his smallest projects. Commissioned to design a public toilet in Ichihara, Fujimoto erected a solid wooden fence in an oval ring around the edges of the site, encircling a bucolic garden in which a loo stands brilliantly exposed in a glass pavilion. You can openly defecate among the birds and the bees, surrounded by plants in the middle of a public place, without ever being seen. “Even in such a small project,” he says, “you can find opportunities to reinvent architecture.”