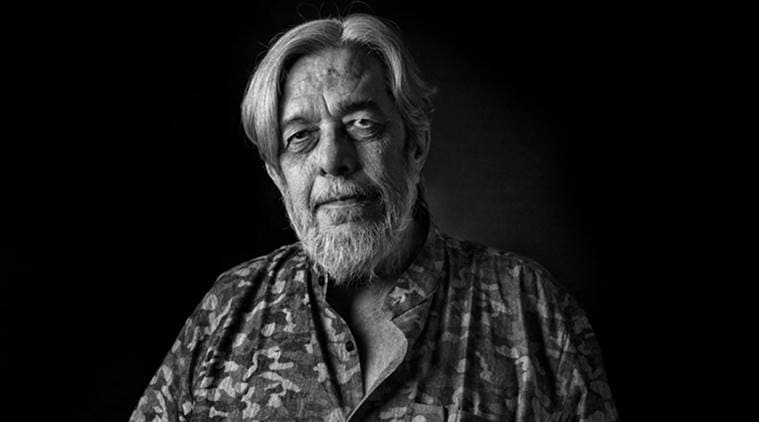

Filmmaker Saeed Mirza.

Filmmaker Saeed Mirza.

Saeed Mirza leans in a little, the glint in his eyes still steely at the age of 75, and says, “If only we threw more shoes.” In his recently released book, Memory in the Age of Amnesia (Context, Rs 499) Mirza writes of Muntadhar al-Zaidi, who had hurled his shoes at then US president George Bush at a press conference in Iraq in 2008. “This is a farewell kiss from the people of Iraq, you dog,” Zaidi had said to Bush.

“Why did he do that? Because he didn’t forget (the role of the US in Iraq war),” says Mirza. “And most of the world was on his side. Because they want to throw shoes, too, at a lot of people. That is why, I wish we (in India) threw more shoes.”

Few will disagree that Mirza has practised what he preaches. With his unapologetic style of filmmaking, he has certainly thrown more than just a shoe at the establishment. In his new book, a collection of essays that throws light on political events in the 20th and 21st centuries, he discusses the implications of societies which choose not to remember. “These are my memories and personal histories in a world order which seems to suffer from amnesia… how else did (Prime Minister) Narendra Modi come to power in 2014?” Those who voted for the BJP, argues Mirza, chose to forget Modi’s record in Gujarat.

It is important to remember, argues Mirza, when an avalanche of misinformation invades our lives every day. “Mass media controls truth and the narrative and unless we see it that way, we have had it. Whether it’s news about a tattoo on Virat Kohli’s chest or Kim Kardashian, there is a lumpenisation of aesthetics, knowledge and minds. And we’ll end up — as we already have — in a world with Yogi Adityanath or an Isis (Islamic State) mullah. That is why memory is important in this age of amnesia,” he says.

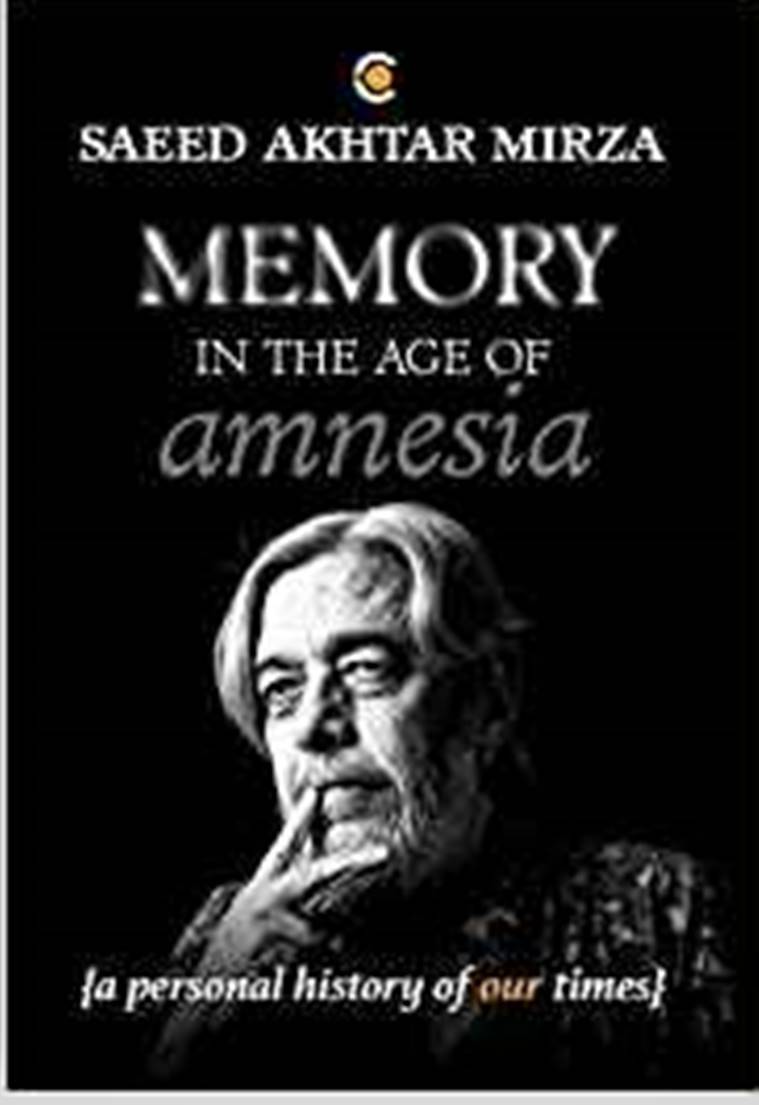

The book ‘Memory in the Age of Amnesia’ by filmmaker Saeed Mirza.

The book ‘Memory in the Age of Amnesia’ by filmmaker Saeed Mirza.

Appropriately, then, the book begins where he was born — at Fonseca Mansion, a 1938-era apartment complex in Mahim, Mumbai, filled with a diversity of people and stories. “I was a vessel, absorbing so many stories, of the people and their hopes, dreams and idiosyncrasies,” he says.

Life at Fonseca, Mirza says, made him perceptive to the rebellion of others. “I used to go to Bombay Scottish school, where kids would get all kinds of savouries and sandwiches for lunch,” says Mirza. One day, a Parsi boy asked him to exchange his paranthas for ham sandwiches. Mirza didn’t know then that pork and ham were the same thing. “I ate it. And when he teased me, I punched him,” says Mirza, who walked home in fear. At the dinner table, Mirza’s father shrugged it off and his mother explained that it was only a sin “when you sin against another human being”. “My mother was an incredibly tolerant woman. Sometimes, I thought she was more Marxist than most without even understanding what it meant. We could argue, have a go at Allah Miyan or Islam — it was all okay,” he says.

Much before Mirza was born, his parents, he says, were coming home after watching a film. “When the show ended, my mother was about to put on her burqa when my father asked: ‘Do you really want to?’ She said no, and that was it. She went home, wrapped it up and put it inside a trunk. I think it’s the quietest revolution in the history of revolutions,” says Mirza.

In a 2016 documentary by Kireet Khurana and P Narasimhamurthy, titled Saeed Mirza: The Leftist Sufi, Mirza talks about the time he didn’t want to offer the Eid namaz. “I must’ve been 10. I happened to see some homeless people outside the mosque and wanted to know why they were poor. It was as simple as that,” he says. Mirza’s father didn’t force him, but “I told him to not tell my mother because I was afraid I won’t get my Eid money.”

Mirza credits Akhtar Mirza, his father and the scriptwriter of iconic films such as Naya Daur (1957) and Waqt (1965), for encouraging him to question. “I liked his films. But I used to wonder why he didn’t push himself or his cinema further, not realising that is how the system is. As a reader, he was far ahead of the scriptwriter he became. From Graham Greene, (Honoré de) Balzac to John Steinbeck, he introduced me to so many ideas and books.”

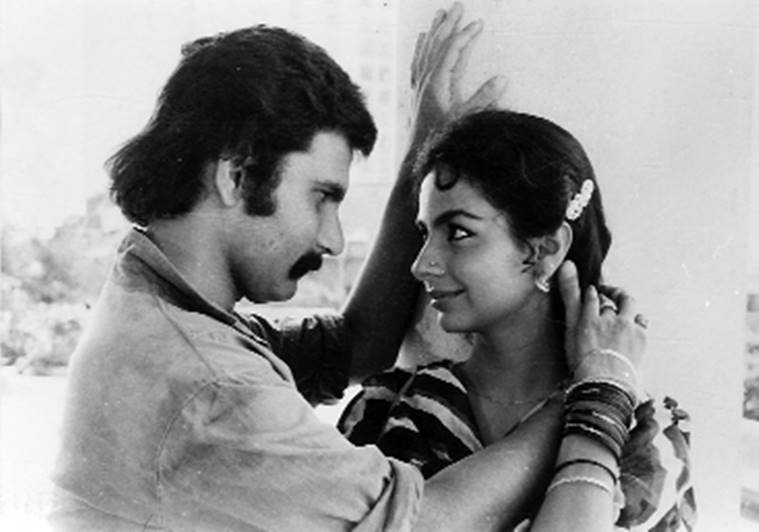

Wide lens: A still from ‘Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro’.

Wide lens: A still from ‘Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro’.

But it is not as if Mirza’s politics was solely a product of his upbringing. “Arvind Desai ki Ajeeb Dastaan (1978), my first film, talks exactly about this. You are born into a certain milieu, with access to books and ideas. But what are you going to do with it? Most of us become part of the system. The point is how do you not become a part of the system?”

He modelled the character of Arvind Desai — the son of a wealthy businessman disillusioned with the system — on himself. Over the years, his rage against the machine grew more strident. Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989) told the story of the minority community in a communally polarised Mumbai. Salim, a small-time local goon, tries to swim to the shores of a better life, but finds it repeatedly out of his reach — largely because he is a Muslim.

If Salim was an ominous cry of help for the nation’s minorities, Mirza says that Naseem (1995), starring Kaifi Azmi, was “an epitaph for my country”. Set in the days preceding the Babri Masjid demolition, Naseem reflected Mirza’s pessimism about the country. “I used to see a lot of poetry in things before. But after Babri happened, poetry was dead. Bulleh Shah had said, ‘Baazi le gaye kutte’ (the dogs have won the game). That is what I felt about the state of affairs at the time, and still do.” The film cast poet Azmi in the role of the protagonist’s ailing grandfather, who tells Naseem (Mayuri Kango) stories of Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb as riots rage in Mumbai. “Kaifi and I knew each other since the late ’70s. We used to drink rum together sometimes. I was glad I cast him. We talk about the end of an epoch. His face depicted that ending,” he says.

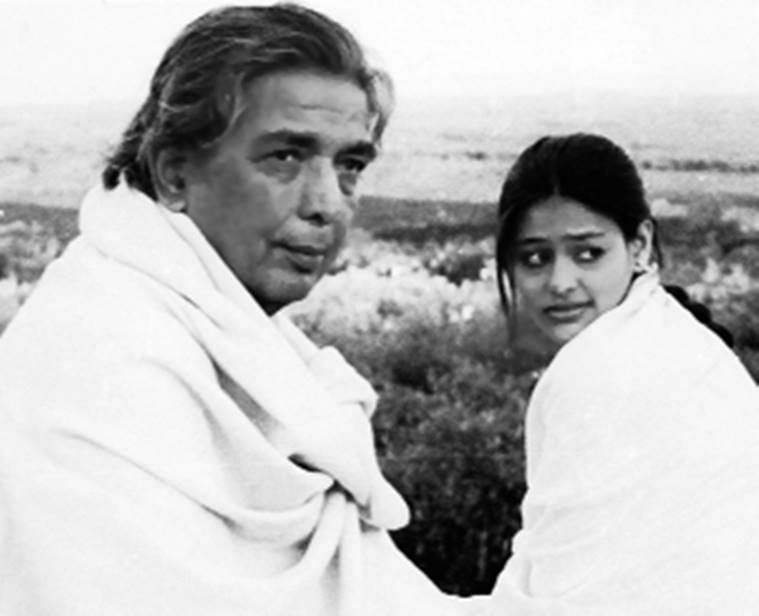

Kaifi Azmi with Mayuri Kango in ‘Naseem’.

Kaifi Azmi with Mayuri Kango in ‘Naseem’.

After Naseem, he “set off across the country with an 18-member crew” to shoot a documentary and find solace in travel. The result was Tryst With the People of India (1997), a 16-part travelogue series produced and directed for the Doordarshan as a part of celebrations of India’s 50 years of independence. Four other filmmakers — Shyam Benegal, Bhupen Hazarika, Buddhadeb Dasgupta and Girish Karnad — had also been commissioned by the government. “I went about asking people their views on India and independence. And I censored none of it,” he says.

Mirza was a bit too honest, perhaps. While the other films were screened during the day, his documentary was shown late at night, on August 14, says Mirza with a laugh.