https://www.timesunion.com/living/article/Waiter-Matthew-Kirshner-tells-his-opioid-tale-in-12997343.php

https://www.timesunion.com/living/article/Waiter-Matthew-Kirshner-tells-his-opioid-tale-in-12997343.php

Waiter Matthew Kirshner tells his opioid tale, in his own arrogant way

After admitting to heroin sale, longtime local waiter has own perspective on opioid epidemic

Updated 12:05 am, Sunday, June 17, 2018

This is not one of the stories from the opioid epidemic that by now are sadly familiar in their outlines.

In this story, nobody dies. Nobody overdoses. Its central character — whom no one, especially not himself, would consider a tragic figure — can seem like an arrogant jerk. Though I don't dislike the guy, I'd still call him that. He'd agree with the characterization, having heard it before.

But in its particulars, his story has its own abundance of addiction-related tawdriness, humiliation, despair and possible redemption.

Meet Matthew Kirshner, all 5-foot-3-inches of him.

"I'm Matthew, not Matt," he said. "Mats get stepped on, especially when they're my height."

He's like that — annoyingly glib. He conceded that his blithe brashness infuriates fellow group members in his court-ordered drug treatment: "They want to throat-punch me."

Articulate and loquacious, the 40-year-old Kirshner speaks in fully formed paragraphs. Many seem rehearsed, even if they're actually not.

He's been crafting those stories by talking a lot — to himself, to cops and lawyers and judges, in group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous meetings, to fellow jail inmates and now to residents at his halfway house — since his March arrest.

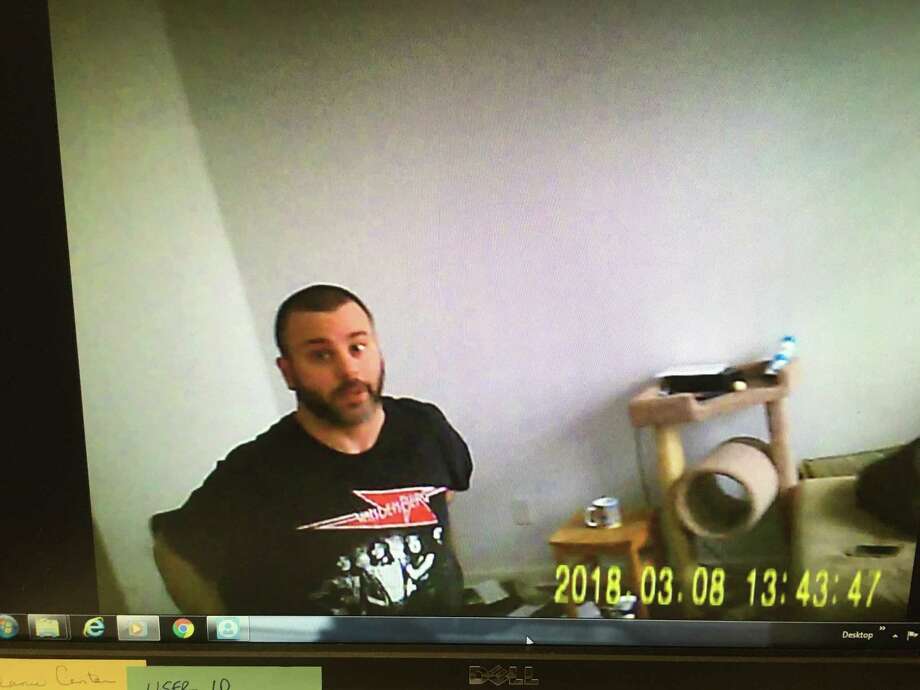

The news release about it, sent out by the Albany County Sheriff's Office, was salacious. It portrayed Kirshner using his Cohoes apartment as a den for heroin sales and prostitution. Police filed a single charge: criminal sale of a controlled substance, a Class B felony with a potential minimum sentence of one to three years in state prison. The charge was for a heroin sale made about five hours before Kirshner's apartment was raided the evening of March 8, his door smashed in by a heavily armed squad.

On this, police and Kirshner agree: He sold heroin. He told me all about it during a 75-minute interview earlier this month. We talked about how he went from Hebrew school in Mamaroneck, to NYU for film production and cinema studies, to a decade as a well-known waiter at the Capital Region's best restaurants, to this: lying handcuffed and facedown on his apartment's carpet while deputies searched the place and quizzed a woman and another man who were also in the apartment. The sheriff's office later would characterize them as a heroin-addicted sex worker and a customer there to meet her for sex and drugs.

Yes, Kirshner acknowledged, all of that happened.

Earlier on the day of his arrest, Kirshner was contacted by someone he knew from the drug scene. Unbeknown to Kirshner, the guy was a confidential informant for the sheriff's office, sent in because cops had heard complaints of the apartment being busy with drug-related visitors. The informant wanted two bundles of heroin, each containing 10 glassine bags of the drug, and each bag holding 0.03 to 0.05 grams.

Kirshner got in touch with a dealer he knew. The dealer agreed to front Kirshner the two bundles and Kirshner would bring back the agreed-upon fee, $180. For this facilitation service, the dealer tossed him a bit of crack, which Kirshner enjoyed. He also used cocaine regularly and, he said, maybe two or three bags a day of heroin. Serious addicts, who shoot up less to get high than to prevent themselves from getting sick with withdrawal symptoms, can go through a couple of bundles a day.

The informant showed up at Kirshner's Main Street apartment around 1:40 p.m. It's all there on high-def surveillance video. Kirshner and the informant gab. The informant seems impressed by a room containing Kirshner's vast media collection, which he pegs at 24,000 CDs, 3,000 DVDs and 2,000 books.

Kirshner can be heard on the video bragging that the heroin he's selling is laced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is up to 50 times more potent than heroin and has been blamed for many overdoses. Kirshner personally vouches for the presence of the synthetic booster, saying, "It's got a fentanyl cut in it. ... I'm feeling that right now."

When Kirshner disappears into his media room to retrieve the bundles, also called buns, the informant turns to a woman who is sitting on the couch and says, "Where's all the girls at?" She says, "You're lookin' at 'em."

After Kirshner passes over the bundles — which is not seen on screen but which all agree happened — he and the informant discuss a future sale, of a sleeve, or 10 bundles, called buns, of heroin and a ball, or 3.5 grams, of crack, for more than $1,000. The second sale never happened. Kirshner said his dealer was reluctant to front that much product, and the sheriff's office said it felt it had enough to get a warrant for the raid based on the single sale.

"That saved me from a much bigger charge, because I would have done that in a heartbeat," Kirshner said.

Five hours later Kirshner was in custody. He was arraigned and sent to Albany County jail. Since it was his first offense and he faced only the single charge, Kirshner was allowed to plead to a lesser count and be sentenced to drug court, which works with offenders to supervise treatment rather than incarcerate them. According to a spokeswoman for the Albany County district attorney's office, if Kirshner successfully completes his court-ordered sentence, his record will show only a misdemeanor conviction for criminal possession of a controlled substance.

In all, Kirshner said he spent 47 days in county jail. He has been in a halfway house since April 24 and expects to be there for three months total, then at least another three months in a supervised apartment. He thinks he will be under the court's jurisdiction — with mandatory treatment, meetings and urine tests for drugs and alcohol — for 17 to 24 months. Failing the program for any reason would send him to state prison for up to three years.

Now that he's out of jail, Kirshner has a few things to argue about, starting with the sheriff's office's characterization of his apartment as a hot spot for the sale of drugs and sex. The news release about his arrest resulted in multiple media stories describing how investigators, responding to complaints from neighbors and Kirshner's landlord, observed "people coming and going from the location throughout the day and night." The release highlighted the fentanyl angle, though, the district attorney's spokeswoman said, "There is no indication in our files that the drugs contained fentanyl."

Said Kirshner, "They play up fentanyl ... because it's become this zeitgeist word, like kale. ... I'm not pushing away my accountability; that's not it at all. But don't latch onto a word as a bogeyman. It's all bad sh-t. Fentanyl becomes this cultural fear, like pins and needles in Halloween candy in the early '80s."

He further disputed that his apartment was a drug bazaar. "In the scene, if you pick up a bun ... and somebody says, 'Hey, can you sell me two bags?' and I've got 10, I'm going to help him out. I was not selling, not the way they portrayed it. ... I've only sold like that once — the day I was arrested."

The sheriff's news release also mentioned the prostitution angle, which many media outlets included in their reporting; the Times Union omitted it, because there was no related charge.

William Rice, chief deputy of the sheriff's office, showed me the video of the buy. He defended the office's allegation of prostitution although no one was arrested for it, saying that both the woman and the second man at the apartment during the raid admitted that's what they were there for.

"They were very honest about it," Rice said. "The reason we mentioned it was because we'd been receiving complaints. It was information, for the community to know the true facts of what was going on, and we also thought having it out there might act as a deterrent."

Kirshner acknowledged he knew that the woman in the apartment during the buy and the raid, someone he said stayed with him occasionally, was a heroin addict who serviced clients to feed her habit. But, he said, "I don't moralize addiction, I don't moralize sex work, and in that scene you tend to rub shoulders with people who do that (work)."

In some ways, he said, he relished the jarring juxtaposition between his two lives. As a restaurant server, he solicitously helped financially comfortable people decide between a $65 bottle of St. Emilion and a $70 Chateauneuf du Pape. He felt equally comfortable in the demimonde in and around his home, where people shot $10, $20, even $40 worth of heroin up their arms at a pop. Kirshner prided himself on being able to navigate both worlds with what he believed was equal aplomb. He said he once sent a crack dealer a text that offered a sommelier's assessment of the drug he'd just bought, saying it showed "bright acidity, crisp minerality, somewhat reminiscent of a Sancerre or perhaps Loire Valley sauvignon blanc."

That comfort had begun to deteriorate in the last few months before his arrest.

"The whole thing had spiraled out of control as a lifestyle," he said. "There were so many situations ... foisted upon me, and I accepted, in exchange for drugs or in exchange for the experience of it. And then that's compounded with a certain fear on my part, not being willing or able to assert my boundaries, to say, 'Get the f--k out of my apartment.' "

How, I asked him, did he get to that point? How does the brainy boy from Hebrew school, the guy who got himself hired by and who charmed customers at restaurants like Yono's and Angelo's 677 Prime and The Brown Derby and so many more, the guy who contributed more than 300 articulate, often eloquent comments on the Table Hopping blog over nine years — how does he end up doing crack, coke and heroin, letting people use his apartment for drug and sex deals and getting arrested?

He said the descent started about four years ago. The following is a verbatim quote, delivered as a complete paragraph without any prompts or followup questions from me:

"After coming off of a very deep psychiatric implosion, if you will — I really came very close to suicide — (I) came out of that, actually, with a newfound sense of compassion, empathy, unloading a lot of the negative emotions that had hamstrung me for so long. Anger, resentment, self-loathing, things like that: Those I jettisoned; those I got rid of. But from that compassion for people around me, more and more people, I came to understand, were suffering from addiction, specifically to coke, crack and heroin, and I wanted to understand their pain. So, 'Go ahead and try it. What's so great about it?' And I went straight for the top. There was no gateway; there were no starters. It was, 'Let's do dope (heroin), let's do some hard (crack) and some coke.' "

I said, "I'm sorry, what? You claim you shot up heroin because you wanted to empathize with people who were suffering? Feeling compassion toward or sorry for them wasn't enough? Come on! That sounds delusional!"

He said, "(T)hat's how it happened for me. It really was. ... I tried it in September 2016, and as mid- to later 2017 progressed, it became more of who I was associating with. If not an addiction according to Hoyle — and I'm not blaming and sloughing off the term 'addiction' — it was certainly habituation and ritualization: the act of lighting up crack cocaine, the act of sniffing coke, the act of having somebody bang dope for me. I didn't do it myself; I have terrible aim. But those acts were in themselves satisfying and ritualistic."

No wonder his fellow addicts in their recovery group want to throat-punch him. I have known people close to me gripped in the fangs of hard-core addiction to heroin and crack. I have been to meetings with them and heard them and others present talk about the allure of the initial euphoria, the warm creep of the high along the spine, the benumbed nod as, for all too brief a period, nothing else matters and everything seems all right. Those parts of their stories match up with Kirshner's. However, I'd never heard anyone talk about sticking needle in a vein as a deliberate foray into an experiential empathetic escapade, though, to be fair, I've never heard anyone talk like Kirshner does — about anything.

But the introspection that produces such expansive justification and ridiculous rationalization also excavates more conventional signs of a road to recovery: "It's sometimes minutes at a time," Kirshner said. "You're a poor decision away from going back. I have to believe that, and I do, sometimes, especially because I have so many compulsions, so many compulsive behaviors. If I f--k up, I max out at three years."

He continued, "I'm accountable, but I'm not going to be penitent for this for the rest of my life. I have no internalized shame over this. I went through this, I'm out of it, and I'm grateful and lucky." Because he's who is he, Kirshner couldn't help adding, "Am I going to cry for penance from strangers? No. Let 'em make the insults; let 'em make the jabs. But I've been reading Dorothy Parker for a month, and I promise them that my wit is sharper right now."

Our interview was nearing its end. His literary sense mindful of the necessity of a satisfying conclusion, Kirshner said, "I don't know if there's contrition in me, and I'm going to leave it for other people to figure out, because I don't necessarily moralize this. I don't look at this from a moral angle as much as most people.

"Have I wronged people? Yes, absolutely. ... Am I a scourge to society because I sold a snitch — somebody with a rap sheet bigger than my ego — two buns? No."

sbarnes@timesunion.com • 518-454-5489