CM H D Kumaraswamy, whose swearing-in brought about the grand turnout, was quick to say that the leaders “wanted to send a message to the country that in 2019, there will be a major change in the political situation”.

CM H D Kumaraswamy, whose swearing-in brought about the grand turnout, was quick to say that the leaders “wanted to send a message to the country that in 2019, there will be a major change in the political situation”.

FIVE chief ministers from five different parties to greet one Chief Minister from a regional party, leaders from parties which otherwise wouldn’t be seen together in public sharing a stage, and a hug and a smile by a much-courted supremo not used to displays of affection in public. A creaky Opposition seeking to send a message to the BJP couldn’t have organised a better montage than that Bengaluru picture, May 23.

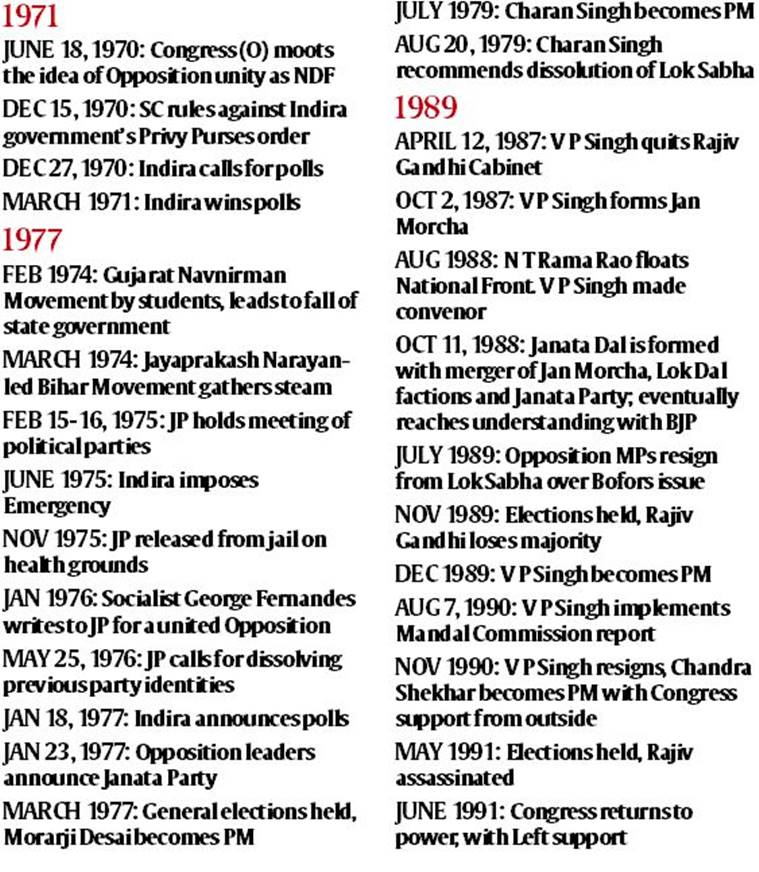

CM H D Kumaraswamy, whose swearing-in brought about the grand turnout, was quick to say that the leaders “wanted to send a message to the country that in 2019, there will be a major change in the political situation”. It won’t be the first time that the Opposition has sought strength in numbers to take on a mighty ruling party with a majority in the Lok Sabha, the three bids before this being in 1971, 1977 and 1989.

The BJP was not late in catching on, at this throwback to the ‘70s. On the Modi government’s fourth-year anniversary, on May 26, BJP president Amit Shah noted that while the Opposition’s agenda was ‘Modi hatao’, the BJP was focused on removing “poverty”. ‘Indira Hatao’ was the united Opposition slogan in 1971. Indira Gandhi had countered it with one that remains timeless: ‘Garibi Hatao’.

But as the two sides take up their positions for 2019, how alike will next year’s general elections be to 1971, 1977 or 1989?

Indira vs NDF

In the general election of 1967, the unthinkable had happened when the Congress, fighting its first election post Jawaharlal Nehru, was reduced to 283 seats — a little over half the seats in the then 520-member Lok Sabha; quite a tumble for a party still bearing the halo of the freedom movement.

While the opposition conservative parties Bharatiya Jan Sangh and Swatantra Party had won 35 and 44 seats, the Socialists had won 46. PM Indira Gandhi, struggling to fill Nehru’s shoes, was also facing battles within. Finally, the Congress split into Congress (O), comprising older-generation regional satraps, and the Congress (R). Indira’s weak government was propped up by Communists and the DMK, which had emerged as a regional force.

After Indira’s attempts to bolster her position through populist measures suffered setbacks in the Supreme Court, she announced early elections, for February 1971. The result was the first-ever experiment of national parties forming a grand alliance for the Lok Sabha polls, loosely called the National Democratic Front (NDF). The Bharatiya Jan Sangh, Swatantra Party and Socialists came together and joined Congress (O) leaders — such as Nijlingappa, Kamraj, Neelam Sanjiva Reddy, Morarji Desai, Ashoka Mehta, and Satyendra Narayan Sinha — to dislodge Indira.

An unnerved Indira too struck a limited pre-poll alliance, with the DMK and CPI.

The Opposition’s formula was ‘one constituency, one candidate’. But it wasn’t without its share of problems, especially in Gujarat. Eventually, the Congress (O) spared only four seats for the Swatantra Party in the state and none for the Jan Sangh and Socialists, with the latter two fielding a few candidates of own.

The Congress-R ended up not just making gains in Gujarat, but across. The NDF managed just 49 seats — the Jan Sangh 22, Congress (O) 16, Swatantra Party 8, and Socialists 3 — against 150 they held in the previous Lok Sabha. Indira roared back to power with 352 seats (out of 518). Allies DMK and CPI too won handsomely, with 23 seats each.

Writing about the election in his book Divided We Govern: Coalition Politics in Modern India, historian Sanjay Ruparelia suggests that Indira’s decisive image trumped the hotchpotch Opposition coalition. “The electorate, fearing that a hung Parliament would exacerbate the politics of opportunism and extremism that had marred the SVD (Samyukta Vidhayak Dal) governments, voted for ‘change and stability’,” he wrote.

The SVD was an informal coalition of parties, including the Socialists and Jan Sangh, formed after the 1967 Assembly elections. To a political watcher, what Ruparelia observed for 1971 holds as true for 2019, with the Opposition trying to rustle up a coalition of disparates. The BJP incidentally holds almost exactly the same number of seats the Congress had going into the 1971 polls.

Already, the seat-sharing cloud is hanging over the sunny picture of Bengaluru, with the Samajwadi Party hinting at trouble in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. But the NCP’s D P Tripathi dismisses a comparison with 1971. “That frail woman (Indira Gandhi) was fighting against her own government and entrenched interests then,” he says.

Adds RJD vice-president Raghuvansh Pratap Singh, “2019 will be very different from 1971. Now we have strong regional parties with committed support bases. The SP-BSP-RLD alliance with the Congress in UP, the JD(S) with the Congress in Karnataka, the JMM-JVM with the Congress in Jharkhand, the RJD with the Congress in Bihar provide a massive base against the ruling party.” The RJD leader also points to the Dalit factor. “Dalits stuck with Indira-Jagjivan Ram in 1971, but they are disillusioned with the BJP.”

Indira vs Janata Party

Two coalitions that were successful in defeating government of the day. (File Photo)

Two coalitions that were successful in defeating government of the day. (File Photo)

If politics is fickle business, this election exemplified it. The 1971 win had been the highest point in Indira’s political career, crowned by a victory in war that is usually enough to see a government through an election. On top of it, it was a victory against Pakistan, cementing Indira’s persona as a strong-willed leader.

But what followed was a series of blunders by the Congress supremo, leading to the Emergency and a crackdown on Opposition, which in turn got them talking of an alliance again.

Unlike 1971, the parties opposed to the Congress decided to subsume their identities into a single Janata Party this time. These parties included the Jan Sangh, Congress (O), Socialists and the Charan Singh-led Bharatiya Lok Dal (BLD). The Swatantra Party had by 1974 merged with the BLD. However, the parties couldn’t formalise the union till polls were announced on January 18, 1977.

The Janata Party was formally announced days later. A week later, veteran Congressman Jagjivan Ram, who had defected from the party to form the Congress for Democracy (CFD), also joined ranks with the Janata Party. The new party allied with the Akali Dal in Punjab and DMK in Tamil Nadu, while the CPI(M) decided not to field opponents.

Eventually, the talks dragged on till so late that the Janata Party contested elections on the symbol of the BLD.

Reflecting on the long negotiations, historian Rakesh Ankit talks about the letters exchanged between JP and other leaders. “An anxious JP appeared helpless in the face of personal predilections on the part of Charan Singh and Congress (O) and a rather mechanical approach by the Socialists and the BJS (Jan Sangh),” he summarises in his paper ‘Janata Party (1974-77): Creation of an All-India Opposition’, published in the journal History and Sociology of South Asia.

“Hindsight has distorted our understanding of the Janata groups by portraying their eventual coming together as something that had to be… their interactions revealed more fault lines within opposition parties than between them and Mrs Gandhi,” he writes.

Despite the hiccups though, the Janata Party and allies won 330 (of 542) seats — the Janata Party won 295 alone. The first ever non-Congress government came to power in Delhi. According to Ruparelia’s book, within the Janata Party, the Jan Sangh won the maximum seats (90), followed by the BLD (68), Congress (O) (55), Socialists (51) and CFD (25). The trouble started soon after, as while the elections had been fought with JP at the forefront, the power pie was carved along factional lines. The Jan Sangh backed Morarji Desai for PM, dealing a blow to the BLD’s Charan Singh, who was critical of the RSS, while the Socialists backed Jagjivan Ram. Finally, Desai won as the Congress (O) leaned too in his favour.

The feud never died down, and Charan Singh eventually brought down Desai to become PM. When his brief stint ended, Charan Singh recommended dissolution of the House rather than let Jagjivan Ram get a shot at power. By August 1979, the Janata Party government had fallen.

For 2019, even the most optimistic opposition leader can’t visualise anti-BJP parties coming together under a single symbol. The BJP hopes that in the absence of this, any seat-sharing talk would be too fractious to be settled. It also calculates that since the parties on the Opposition side are regional, apart from the Congress, they would not be a force multiplier beyond their areas of influence.

Shah said as much in a May 21 conference, remarking, “Will Deve Gowda (JD-S) contest in Bengal? What will Mamataji (Banerjee) do in Karnataka or Chandrababu Naidu do outside of Andhra?” He also claimed that for the BJP, taking on those parties wouldn’t be new. “Even in the last polls, they were all against us.”

However, even Shah won’t be as complacent about do-or-die UP, where an SP-BSP alliance has already proved a game changer. But this tie-up is already feeling the heat. A senior SP leader notes wryly, “Not many people noticed, but there was no BSP representative at the iftaar hosted by Akhilesh Yadav in Lucknow recently.”

Signs of discord are emerging in not just UP. Akhilesh also said last week that the SP had plans for Madhya Pradesh, and hinted that these didn’t include potential ally Congress. An Opposition MP from UP explains, “There is concern among regional parties about allying with the Congress beforehand. It amounts to becoming a part of the UPA and takes away their flexibility… One can always bargain hard with the Congress post polls.”

But such a disjointed front, scampering for spoils later, would just be what the BJP would want. In a recent interview to The Indian Express, Home Minister Rajnath Singh said, “Leader is always one… Once Atalji was popular, now Modiji is… At these times, opposition parties need each other… People will say how will so many people come together and run a government?” For now, leaders like the RLD’s Jayant Chaudhary, fresh from the Kairana bypoll win forged from this unity, say the Opposition is willing to put differences aside for defeating the BJP. He also plays down possibility of differences post polls, saying the leader of the largest party would naturally be the PM.

Rajiv vs National Front

Two coalitions that were successful in defeating government of the day. (File Photo)

Two coalitions that were successful in defeating government of the day. (File Photo)

It would take 10 years after the collapse of the Janata Party government for the Opposition, bearing the wounds of losing to Indira in 1980 and being trounced by Rajiv Gandhi in 1984, to try the experiment again.

While Rajiv had come to power with 404 seats (of 514) in the 1984 elections, held after Indira’s assassination — in the biggest majority till then, and since — several small blunders had chipped away at the goodwill. The biggest blow was dealt by V P Singh, who quit the Rajiv Cabinet riding the Bofors scandal, left the Congress and formed the Jan Morcha. In a year, it had morphed into the Janata Dal, along with the Janata Party, the Lok Dal (A) and Lok Dal (B) (splinter units of the BLD).

The Janata Dal then forged the National Front (NF), with the Telugu Desam Party, Asom Gana Parishad and DMK, with the Communists lending their support. While the BJP was initially kept out due to the CPI(M)’s reluctance, the Janata Dal reached out to it as well after the BJP’s stellar performance in UP local body polls in 1988-1989, and after it got the support of Haryana stalwart Devi Lal.

In a cleverly crafted seat adjustment, the BJP and Janata Dal eventually faced each other in only 44 constituencies in the 1989 elections in the Hindi heartland. The BJP, which had slumped to 2 Lok Sabha seats in 1984, got 85.

While the Congress still emerged as the single largest party, it won just 197 seats. The Janata Dal won 143 seats, and V P Singh became PM backed by the BJP and Left Front (52 seats) from outside.

However, the fate of the 1989 government was similar to the Janata Party’s. Devi Lal played a key role in getting V P Singh the chair, leaving Chandra Shekhar visibly disappointed. Finally, the personal ambitions and political turf wars of V P Singh, Devi Lal, Chandra Shekhar and the BJP, which had moved on to ‘Ram temple’, dragged the government down in 1990. Chandra Shekhar formed a government with the help of the Congress, only to be pulled down within months on frivolous grounds.

In the 1991 elections that followed, the Congress returned to power, but backed by the Left. The era of coalition governments at the Centre would eventually last till 2014, when the BJP won a clear majority.

Congress chief Rahul Gandhi has said that for 2019, parties traditionally opposed to each other have a bigger motivation to come together than ever. “It is the sentiment of the people, and not just parties to have a ‘mahagathbandhan’,” he said in Mumbai on June 11. Others in the Opposition again hark back to the Bengaluru stage, where arch-rivals at state level the SP and BSP (Uttar Pradesh), the TMC and CPI(M) (West Bengal), and the Congress and CPI(M) (Kerala), came together.

Modi vs who

With the BJP mopping up a series of electoral gains since 2014, no opposition party denies that unity is the need of the hour. But the shape and contours of it are far from clear. Having seen the 1971, 1977 and 1989 poll battles from inside the ring, Union minister Ram Vilas Paswan is clear which one 2019 resembles. “The Syndicate contested against Indira in 1971. They all got out cheaply. 2019 will be similar to 1971. The Opposition will get out cheaply,” he says.

About 1977, he adds, “It had a genesis in the student movement that started in 1974. A JP-like leader acted like a paper-weight on the ambitions of big leaders. There was also a pre-poll alliance in 1977. Now there is no such alliance and Rahul Gandhi is not acceptable to Mamata Banerjee, nor to Chandrababu Naidu.”

Counters Congress Rajya Sabha member Jairam Ramesh, “In 1977, Indira Gandhi was tarred by the Emergency. But Indira of 1971 was the Indira of bank nationalisation, of abolition of privy purses. In my view, Indira was at her magnificent best in 1971. Harking back to 1971 is misplaced in the current situation.”

He adds, “2019 is more likely to be 1977, as we have an undeclared Emergency now. The other model is 2004, where we had pre-poll alliances in certain states but there was no national alliance. The UPA came into being later.”

The RJD’s Raghuvansh Prasad Singh says that going forward, the Opposition “will have to let state rivalries be confined to states, while uniting at the national level.” Jairam Ramesh says that this is why, Karnataka, where the Congress offered chief ministership to the JD(S) despite having double the number of MLAs, counts. “It reflects a huge paradigm shift for the Congress,” he says.

“Looking at 2019, there has to be one strategy, and there has to be another strategy post-2019. But, if we miss 2019, our post-2019 strategy may be of no use… What’s our strategic objective? To get the BJP out of power is the most overpowering objective,” he adds.

And so, say other opposition leaders, it is wrong to look back for any hints. Says JD(U) rebel leader Sharad Yadav, who was a prominent face in the 1977 and 1989 elections, “Nai paristhiti hai, naya daur hai, nai golbandi hogi (This is a new situation, a new era, there will be new realignments).”