The most Talking-Heads-esque of Byrne’s solo albums, albeit with a Latin-American influence, Uh-Oh vanished unheralded at the height of grunge. It is far better than its commercial failure suggests – Hanging Upside Down should have been a hit – but also serves to make the listener miss Talking Heads, which presumably couldn’t have been further from Byrne’s aim.

The soundtrack to Byrne’s directorial debut was made as the band was falling apart and it is tempting to say you can tell. The weakest Talking Heads album, it feels simultaneously laboured and undercooked: the sound is leaden; Puzzlin’ Evidence and Papa Legba amount to padding. And yet it is still sprinkled sparingly with magic, not least the wistful Dream Operator.

A collaboration with Brian Eno that also enlisted Sampha and Oneohtrix Point Never, American Utopia attempts to salvage something positive from Trump’s first year in power, a risky undertaking that perhaps inevitably misses as often as it hits. As it lurches from great to grating – on I Dance Like This, this happens in the space of one song – you could never accuse Byrne of resting on his laurels.

There is no doubt a 90-minute concept album about Imelda Marcos featuring guest appearances from Florence Welch, Sia and Cyndi Lauper is a tough sell, but Here Lies Love is surprisingly great: the songs are sparky – as dance producers go, Fatboy Slim has always been big on pop hooks – the story is legible and Róisín Murphy’s turn on the disco-infused Don’t You Agree? is a delight.

Not everything on Look Into the Eyeball’s eclectic menu is fantastic, but it is substantially more fun than its predecessor, Feelings, on which Byrne dabbled awkwardly with drum’n’bass and trip-hop: indeed, on its two collaborations with legendary soul producer Thom Bell, it has a genuinely infectious euphoria about it, suggestive of an artist once more finding his groove.

The Oscar-winning soundtrack to Bertolucci’s film is divided down the middle: Ryuichi Sakamoto’s score melds romantic strings with Chinese instrumentation, but Byrne’s consists of a variant on what Can would have dubbed ethnological forgeries: his own interpretation of Chinese classical music, played largely on traditional instruments.

Talking Heads’ last big push returned to the sonic density of Remain in Light, with South America replacing west Africa as a rhythmic source. If it feels like much harder work than the album it is modelled after, perhaps that was the point: its mood is troubled, bleak, even apocalyptic.

Anyone expecting a retread of Byrne and Eno’s earlier collaborations was in for a shock: their reunion yielded pop, country, gospel, breakbeats and Byrne yodelling. The lyrics are haunted by the Iraq war and everything is given a shimmer of weirdness by Eno’s production. The result is low-key but endearing.

Talking Heads’ 2m-selling commercial peak dialled down the experimentation in favour of streamlined, literate, grownup pop. Something was undoubtedly lost along the way, but the results are charming nonetheless, from the breeziness of And She Was through to the darker, more angsty Give Me Back My Name and the deathless Road to Nowhere.

11 David Byrne – Lead Us Not Into Temptation (2003)

An intriguing return to Byrne’s homeland of Scotland, his soundtrack to Young Adam paired him with various members of Belle and Sebastian, Snow Patrol and Mogwai, among others: you can hear their influence on the sound, which tends to post-rock, beautifully evocative of the damp, chilly landscapes of the film’s setting.

Lavishly orchestrated and featuring Rufus Wainwright duetting with Byrne on a Bizet aria and Lazy, his X-Press 2 collaboration, reworked for high-drama strings, Grown Backwards should not work, but it really does: Byrne’s voice sounds fantastic and his knotty, funny meditations on ageing politics and corporate sponsorship hit home.

Byrne’s score for Twyla Tharp’s ballet was so akin to Talking Heads that the band performed two songs from it live: you can hear a similar blend of polyrhythmic funk and twitchy nervousness here as on Remain in Light. The songwriting is ironclad throughout, while the superb Red House dabbles in the same early sampling techniques as My Life in the Bush of Ghosts.

There is a sense in which Talking Heads’ debut album is their most influential: its trebly guitars, sparse sound, jerky rhythms and strained vocals made it a key post-punk/indie text. On 77, Talking Heads sound like a band that arrived fully formed, a unique sound and lyrical style all in place. As it turned out, nothing could have been further from the truth.

The late 80s were packed with pop stars dabbling in world music, but Byrne’s first post-Talking-Heads solo album is a cut above and an underrated joy: he clearly has a love and an innate understanding of Latin and South American music. The songs are uniformly strong and fit perfectly with their musical setting.

With Eno out of the producer’s seat, this album’s simplified sound lost some of its predecessor’s experimental edge. But it makes up for any shortfall with impeccable songwriting: Burning Down the House, Slippery People, the haunting This Must Be the Place.

Byrne’s collaboration with Annie Clark never felt like two artists trying to stitch their styles together: it was a creative union that sparked, spawning something completely coherent and significantly different from their respective back catalogues. Leaning heavily on brass arrangements that range from funky to whimsical to subtle, its dry ruminations on the weirdness of life are genuinely funny.

More expansive than Talking Heads’ debut. Eno’s production adds colour and sonic depth and Byrne’s writing moves on, too, as evinced by the astonishing closer, The Big Country: lambent slide guitar, lyrics that view middle America from an aircraft window and conclude: “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me.”

The opening rhythmic clatter of I Zimbra made clear that Talking Heads had shifted into an entirely different gear. Fear of Music is looser, stranger, funkier and darker – its second side is the most disturbing music they ever made. The sense of a band mapping out their own territory is impossible to miss.

A tapestry of found sounds from radio broadcasts over tape loops and funk rhythms, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts did not invent sampling, but no one had foregrounded the idea in the way Byrne and Eno did, ultimately changing the sound of pop in the process. Cutting-edge experimentation tends to date, but this still sounds fantastic 35 years on.

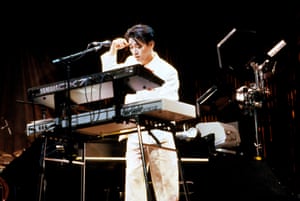

Apparently made by a band in a state of turmoil – who was arguing with whom and about what depends very much on whose version of events you believe – and a commercial flop on release, Remain in Light is Talking Heads’ vertiginous creative zenith: a thick, broiling stew of sound into which was stirred funk, Afrobeat, early hip-hop and Eno’s ambient experimentation. The end result is futuristic, visionary and required a 10-piece band, including two bass players, to reproduce live. Moreover, it is unique: for an album that has been claimed as an influence by countless artists, Remain in Light still does not really sound like anything else.