Leo Varadkar has been Taoiseach for a year.

Since taking power he’s lost a tánaiste, made a friend in Donald Trump, been listed by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world, and faced increased domestic challenges, including homelessness and growing waiting lists.

1. Political tightrope walking

Leo Varadkar walked into a controversy in his first days as Taoiseach following the appointment of the then attorney general Máire Whelan to the Court of Appeal.

It was criticised by the Social Democrats for being "nakedly political" and it damaged relations with Independents and Fianna Fáil.

Months later, another controversy threatened to bring down the Government.

It involved Tánaiste Frances Fitzgerald and what she knew or didn’t know about the legal strategy being deployed by the garda commissioner in relation to whistleblower Sgt Maurice McCabe at a State commission of inquiry in 2015.

For days, when many in his own party thought he would ask the Tánaiste to step down, Mr Varadkar walked a political tightrope, publically backing Frances Fitzgerald, while at the same time knowing her continued presence in Government would result in an unwanted general election.

The crisis was averted when Ms Fitzgerald stood down of her own volition. The Taoiseach said "a good woman" was leaving office without getting a "full and fair" hearing.

But while Leo Varadkar is usually decisive, for some of those who know him, his handling of this controversy raised questions about whether or not he has the killer instinct at the big moment. Did he allow things to drift and events to take over?

If true, this could be a crucial factor in determining the timing of the next election, as the Taoiseach will soon have to decide whether to engineer a new agreement with Fianna Fáil or go to the country.

There is an argument for going to the polls while support for his party is strong, but there are risks too. It’s a big call to make.

2. Big promises

Frank Underwood, the Machiavellian fictitious president in the Netflix series House of Cards once said "the nature of promises is that they remain immune to changing circumstances".

It’s a piece of wisdom Leo Varadkar may do well to take note of.

Promises of "bulletproof" and "cast iron" guarantees on Brexit were made at a time when the full script in the Brexit drama has yet to play out.

Promises of swift answers for women with cervical cancer look to be in doubt, following delays to the Scally scoping inquiry.

When he took office a year ago, Leo Varadkar pledged "to build a republic where every citizen gets a fair go" and a health service with greater levels of patient access.

But his critics have been quick to point out that promises differ from actions, and that he presides over a country in which almost 10,000 people are homeless, a third of them children.

Child poverty too, remains "stubbornly high" according to the charity Barnardos.

Add to that the other seemingly intractable problem of waiting lists, thousands of patients on trolleys, fuelled by a population that is growing older, and a health service that is in need of major reform.

The Government argues that plans are in place to address both the housing and health problems, and that its strategy, particularly on housing, is starting to work.

But by any measure, progress is interminably slow, and as the nature of both problems changes by the day, big promises are more difficult to keep.

3. Shamrocks and socks on the international stage

In his first 12 months in office the Taoiseach met a string of international leaders (May, Merkel, Macron, Trudeau, Trump, and Tusk to name a few) and clocked up a fair number of air miles to match.

He has used his bilateral meetings to promote important trade links and make useful diplomatic ties on whom Ireland may come to rely after Brexit.

But on more than one occasion, there have been raised eyebrows during Leo Varadkar’s international meetings.

His off-the-cuff remarks in London, when he referenced the movie Love Actually and said his visit to 10 Downing Street was "a thrill" or in Washington DC when he spoke about intervening in a planning application for US President Donald Trump’s Doonbeg golf course gave rise to criticism.

Then there were the novelty socks, and that run with Justin Trudeau in Phoenix Park showing the Taoiseach is not averse to enhancing his own image when he gets the chance.

But by and large, the Taoiseach has been positively received during his international visits, with Donald Trump telling him "we’ve become friends, fast friends, over a short period of time".

4. It’s the economy, stupid.

The juice that keeps politicians in power is the economy.

If the economy is strong, people tend to like the Government a little bit better, and Leo Varadkar knows this.

Asked in the Dáil this week about his anniversary, the Taoiseach said he was "not one for anniversaries or birthdays" and was "known to forget them, or decline to celebrate them".

That said, he just happened to have a handy list of eight achievements ready, just in case he was asked about his first anniversary in power.

Six out of the eight achievements related to the state of the economy.

"Record levels of employment, balanced the books, improved living standards, reduced income inequality, reduced poverty, and reduced deprivation."

While it is true that the country is close to full employment, and economic success takes careful management, this did not happen in just one year.

But we expect this to be a recurring theme. When an economy is thriving, governments would be foolish not to let the electorate know who is in power when the good times roll.

5. Communications and spin

The controversy over the Strategic Communications Unit, which was wound down following a blaze of publicity over the placing of advertorials in newspapers, caused his opponents to accuse Leo Varadkar of having a deep "obsession" with spin.

The Taoiseach says he views communications as a positive thing, and he has consistently utilised modern methods of reaching out, to enhance his personal brand.

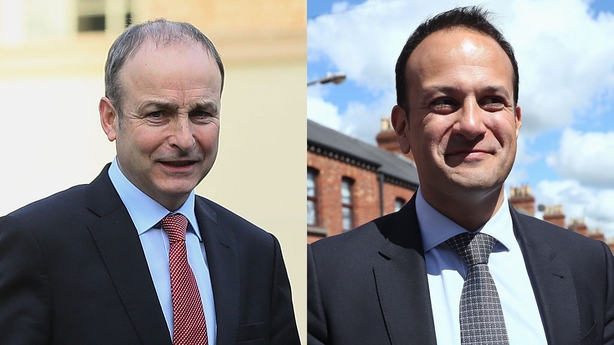

When the Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin criticised Leo Varadkar for recording a social media video on the government jet last year, the Taoiseach defended it, telling him "things are a bit different now".

Videos negated the need "to type up a printed statement which is what would have been done in the past", he said.

It was a new way of doing things. But Mr Varadkar’s attempts to improve communications have had mixed results.

His colleagues in Government will tell you that he is in regular direct contact with them on issues of importance.

He keeps a clear line of communications open with TDs, and responds to their queries.

He practices and rehearses important speeches, often seeking the input of colleagues on his performance, and he places a value of how a message is delivered.

But it has resulted in a consistent line of attack from the opposition – that ‘real’ politics involves delivery on critical issues, rather than viral videos, practiced statements and PR.

6. Robust approach

There was a moment few years ago when, as a young Fine Gael TD, Leo Varadkar took on the then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern.

It was during a motion of no confidence in Mr Ahern, who faced criticism over tribunal revelations that he accepted large sums of money in the early 1990s.

As the motion was being debated, the young Leo Varadkar said the affair would "darken the Taoiseach’s record in the same way as Tony Blair's involvement in Iraq or Bill Clinton's personal scandals darkened theirs".

The remark wounded Mr Ahern who took offence to being "castigated" by a "new deputy who wasn’t a wet day in the place". "I’d say he’ll get an early exit," said Mr Ahern.

He was, of course, wrong.

Today, 11 years after that intervention, Leo Varadkar’s Dáil performances have at times been equally cutting, and often combative.

He clashes regularly with Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald, who he once likened to the far right politician Marine Le Pen, in the way she "always goes back to her script".

He has lambasted Green Party leader Eamon Ryan over what he said were the double standards of the Green Party.

"They don’t just disagree with you, they’re also a better person than you."

And recently he attacked Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin over what he claimed were "dishonest" promises on spending, a remark that prompted the Sinn Féin leader to suggest there was "trouble in paradise".

But while his Fine Gael colleagues like the way he deals with the leaders’ questions, there is also a danger of running too close to the fire by repeatedly attacking the party that keeps him in power.

7. Building bridges

The resignation of Frances Fitzgerald provided Leo Varadkar with the space for a useful bit of political bridge building.

By installing Simon Coveney, his only rival for the leadership of the party, as his Tánaiste, he was able to unite the two factions that had opened up in Fine Gael during the leadership contest.

Leo Varadkar’s capacity to engage maturely with rivals has also allowed him to maintain a reasonably good working relationship with the Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin.

In recent times we’ve also seen a new dimension to the Taoiseach’s capacity to build bridges: a warming of relations between Fine Gael and Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin supported Government legislation on the appointment of judges, in return the Government pledged to support a Sinn Féin initiative on sentencing guidelines.

All of this, as Sinn Féin’s new leader Mary Lou McDonald signals a more open attitude towards entering coalition with either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael.

Whether this new blossoming relationship will ultimately result in a new partnership remains to be seen, but Leo Varadkar has demonstrated an ability to do the necessary deals to maintain power.

8. Reading the public mood

Arguably one of Leo Varadkar’s greatest strengths is his ability to read the mood of the electorate.

As a minister he caught public attention when he described the actions of garda whistleblowers as "distinguished" when one of their superiors branded their actions "disgusting".

More recently during the passing of the referendum on the Eighth Amendment he displayed political skill in the management of his views.

By reserving his opinions until after the Oireachtas Committee had finalised its report, and by displaying an understanding of people’s reservations about allowing abortion without specific indication, up to 12 weeks, he displayed an understanding of the nuanced position with which voters were grappling.

Now, as the clock ticks closer to the next election, this political sixth sense will be essential if Leo Varadkar wants to avoid being a one-term Taoiseach.