They were often innocuous landscapes, conservative portraits and colourful modernist abstract paintings of nothing in particular, but to the Nazis the artworks were “sick”, “twisted” and “filth”.

The story of German “degenerate art” and the British defence of it is to be told in a display opening to the public on Wednesday at the Wiener library in London, the world’s oldest archive of material on the Holocaust and the Nazi era.

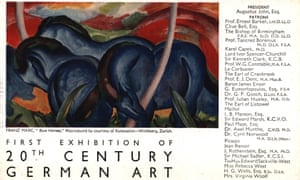

It will tell the story of a groundbreaking exhibition of German art held in July 1938 at the New Burlington galleries in London as a direct response to the famous “degenerate art” exhibition staged by the Nazis in Munich in 1937.

The latter displayed works by artists including Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, with labels such as “an insult to German womanhood” and “nature as seen by sick minds”. The former showed work by many of the same artists in a more celebratory mood. The flyer told potential visitors, with remarkable understatement: “Much of this art is now in official disfavour in the country of its origin”.

It was an important exhibition and showed more than 300 works, according to Barbara Warnock, a co-curator of the Wiener display. “It remains the largest exhibition of modern German art that there has ever been in Britain.”

The Wiener has borrowed two paintings that were in the original show: Max Slevogt’s The Panther, 1931, and Emil Nolde’s The Young Academic, 1918. Ironically, Nolde was a supporter of the Nazi party. He was neither Jewish nor communist, but he was an expressionist and so was condemned.

Warnock said the intention was to highlight the wider context and the human stories around the 1938 exhibition.

For example, the Nolde was loaned to the 1938 show by Ernst Nelkenstock, a Jewish German lawyer forced out by the Nazis who resettled with his family in London in 1936. Unable to practise law in Britain, he opened a butcher’s shop. In 1947 he and his family became naturalised Britons and changed their name to Norton.

The display includes reproductions of some of the 1938 works, including Max Pechstein’s Fishermen’s Horses, 1919, Kandinsky’s Untitled Improvisation II, 1914, and Max Liebermann’s 1925 portrait of Albert Einstein.

The portrait was probably sent to the exhibition by Liebermann’s widow, Martha, who was still in Berlin, in the hope it would be sold. It was bought by the Royal Society, but whether the funds reached Germany is unknown. Martha Liebermann killed herself in March 1943, aged 85.

The Wiener display also includes artefacts and documents from its archives telling the story of displaced Jews arriving in Britain before the war.

One pamphlet given out to all Jewish German and Austrian refugees reads: “The traditional tolerance and sympathy of Britain and the British Commonwealth towards the Jews is something which every British Jew appreciates profoundly.”

It goes on to advise refugees to be be patriotic and loyal and not to speak German in public if they can help it.

• London 1938: Defending ‘Degenerate’ German Art is a free display at the Wiener Library in London, 13 June – 14 September.