https://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Is-drug-versus-drug-an-answer-12981769.php

https://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Is-drug-versus-drug-an-answer-12981769.php

Is drug versus drug an answer?

Movement urges use of marijuana as a way to reduce the nation's reliance on opioids

Published 10:43 pm, Saturday, June 9, 2018

Julie was skeptical, but she was also in pain.

That's how one day, she found herself sitting in her suburban Capital Region home, taking a drug that she remembers the government demonizing when she was a teenager in the '60s. Her friend was there with her and shared some of her stash, which the friend was using to treat cancer pain. Julie remembers telling her it didn't seem to be working.

"Then little by little, as we were talking, my pain disappeared," she recalled. "It was gone — completely gone. On the opioids, it was never completely gone. I was always aware of it."

Julie was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis decades earlier. The disease affected her balance so that by the time she was in her 40s, she suffered chronic back pain from all the times she had fallen. It acted up whenever she sat too long or did chores around the house. Her doctor prescribed her slow-release oxycodone to manage the daily pain, and a fast-release version to take whenever she was on the verge of tears.

That was 20 years ago. Today, she doesn't need any of it. After two decades on opioids, she made the switch to a tincture form of medical marijuana in February.

"It's amazing that doctors will readily give you opioids, a drug that's harmed so many people, but just hearing the word marijuana causes some people to go crazy," said Julie, who requested not to use her full name for fear of alienating loved ones with different views on marijuana.

A new tool in the fight against opioids

Julie was lucky. She never became addicted to the opioids her doctor prescribed. More than 11 million Americans abused prescription opioids in 2016, and another 1 million used heroin, a cheaper, illicit opiate. More than 2 million were diagnosed with an opioid use disorder. Nationwide, two-thirds of all drug overdose deaths that year — the most ever recorded in the U.S. — involved an opioid.

Now, in 2018, public health officials and advocates are urging the medical field and policymakers to take a serious look at marijuana as a tool for reducing the nation's reliance on opioids.

Most people begin taking prescription opioids to treat chronic pain — a condition that, as of last year, New York allowed to be treated under its medical marijuana program. The program started in 2016, first targeting patients who experienced pain from cancer, multiple sclerosis and other conditions. Last year, after numerous pleas, it added chronic pain.

As of Friday, there were 58,451 patients certified to use medical marijuana in New York — 37,786 of whom have chronic pain as a qualifying condition, according to the state Health Department.

But experts say not enough health practitioners are taking advantage of marijuana as a treatment tool — whether due to the burden of getting certified, ignorance about its benefits or its stigma.

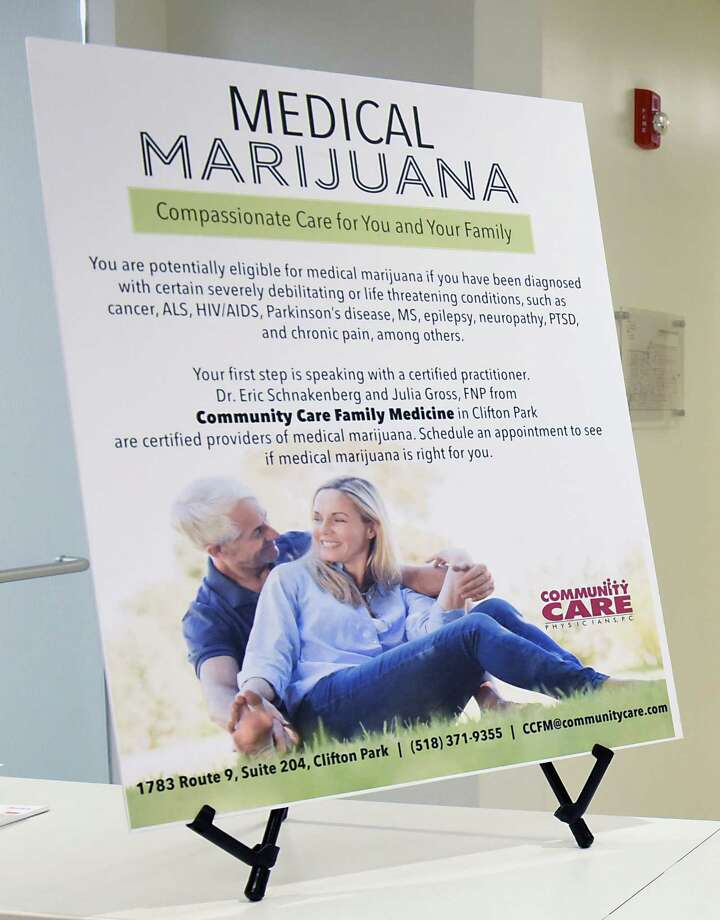

"We have very little experience in the physician community with medical cannabis," said Dr. Eric Schnakenberg, a physician with Community Care Family Medicine in Clifton Park. "It's the newness of it, the unknown of it. We're just awfully ignorant of the benefits. But ultimately our patients are how we learn. The more who use it and have a positive experience, the more I've come to embrace it."

Schnakenberg and his colleague, Julia Gross, a nurse practitioner at the same practice, began recommending medical marijuana to patients in October. Today almost all of the 90 patients they've certified for medical marijuana are using it for pain relief. (Marijuana is also effective at treating PTSD and mood disorders, according to research, though New York does not allow its use for the latter).

But how does it work?

Marijuana contains tetrahydrocannabinol, THC; and cannabidiol, CBD, chemical compounds that bind to endocannabinoid receptors in the brain and elsewhere and produce a variety of effects — they can reduce pain, anxiety and nausea, increase appetite and, yes, get the patient high.

But scientists have figured out a way to measure out and dose THC and CBD in precise ratios, reducing the former to get rid of the high associated with pot and increasing the latter to produce more anxiety relief.

"It's one of few substances that can treat pain in all three areas where we perceive pain — the central nervous system, the spinal cord and the periphery," said Dr. Stephen Dahmer, chief medical officer at Vireo Health of New York, a medical marijuana grow and production facility in Fulton County.

"And it's impossible to die of an overdose," he added.

Not so with opioids, which slow and stop breathing in high dosages.

Vireo is at work on a long-term study funded by the National Institutes of Health to investigate whether marijuana treatment can lead to a reduction in opioid use in adults with chronic pain — something it's already heard anecdotally but hopes to confirm with rigorous research.

Marijuana vs. opioids

It helps to remember that, for a long time, Americans went without treatment for chronic pain. It wasn't until the 1980s and '90s that doctors began treating pain as a "fifth vital sign" — and prescribing painkillers like Vicodin, oxycodone, hydrocodone and morphine.

As we've since learned, many of the makers of these drugs misled physicians and the public about their addictive properties. By the 2000s, hordes of Americans were hooked. Once state governments began cracking down on prescriptions, they turned to a cheaper drug — heroin. The arrival and recent expansion of fentanyl, a synthetic opiate 50 times stronger than heroin, on the black market has contributed to a rapid rise in overdose deaths that officials predict will continue into the next decade.

Marijuana could be an effective early intervention tool when it comes to curbing the epidemic, advocates say. Start chronic pain patients on medical marijuana in lieu of opioids, and they won't risk forming a potentially deadly addiction in the first place, they argue.

"What do we look for in a great medicine?" Dahmer said. "We look for safety, tolerability and efficacy. If it doesn't work, there's no sense in taking it. We have seen good evidence that medical cannabis is efficacious. Patients seem to tolerate it well across the board. As for safety, there is an addictive quality to cannabis, but it's far less than most medicines."

Julie, who took opioids for 20 years before turning to medical marijuana, said oxycodone came with undesirable side effects.

"It's embarrassing, but the worst side effect was the constipation," she said. "It was a living hell. I don't have that anymore."

So far, she hasn't experienced negative side effects from the marijuana. But some patients have reported feeling "loopy" or "out of it," which Dahmer believes can be corrected by altering the THC-CBD ratio in their dose.

James, a 59-year-old from Clifton Park, began taking medical marijuana in March at the recommendation of his doctor. He requested not to use his full name due to fear of stigma at his job.

James had been taking various medicines and painkillers for about five years — first the non-opioid pregabalin (known by its brand name Lyrica), then tramadol, then hydrocodone (both opioids) — in hopes of alleviating nerve pain in his feet caused by diabetes.

"It's so debilitating at times that I can't sleep," he said. "I'd wake up in the middle of the night and then be in no shape to go to work the next day. I was a mess."

This year, his doctor recommended medical marijuana. In March, he registered with the state Department of Health and received his medical marijuana card a few days later. He paid $150 for a monthly supply he picks up at a dispensary in Albany, and said he can sleep through the night.

"It's like a 98 percent improvement," he said. "I haven't touched any of the hydrocodone, any of the tramadol. I still do the Lyrica, but it's excellent. I'm not falling asleep in the middle of the day anymore."

Barriers to expansion

There are 1,684 physicians, nurse practitioners and other medical professionals registered to certify patients for the state's medical marijuana program.

That number should be higher, proponents say, but many in the field remain ignorant to the medical benefits or retain the view that the drug is a gateway to other, more dangerous drugs, said Dahmer and Schnakenberg.

It doesn't help that the FDA doesn't acknowledge the medical benefits of marijuana. Advocates point to studies disputing this claim, and have filed petitions urging the FDA to reconsider this view.

"If I'm a physician and I'm prescribing a new drug in my practice, one I haven't done before, it usually comes to me through a process," Dahmer said. "It's been FDA-approved, it has rigorous scientific research behind it and, typically, it's been brought to me by a pharmaceutical rep. Marijuana does not fall into any of these categories, so it's been a real leap for the field."

The process for practitioners to register with the state is also "a little onerous but doable," in Schnakenberg's view. He had to take a four-hour course and pay a certification fee — something his oncology colleagues said they don't have the time to do.

"It's just one more thing for them to add to their plate, and I think that's the case for a lot of physicians," he said.

State health department spokeswoman Jill Montag said practitioners may also be hesitant to recommend a course of treatment for patients who may not be able to complete it due to the cost. Because marijuana remains illegal under federal law, insurance won't cover it.

"Ultimately, federal reforms are necessary to enable the program, and other state medical marijuana programs, to reach their full potential to help patients," Montag said.

bbump@timesunion.com • 518-454-5387 • @bethanybump