-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-5',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 5',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-10',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 10',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-15',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 15',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-20',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 20',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-25',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 25',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-30',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 30',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-35',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 35',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-40',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 40',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-45',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 45',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

-

-

-

-

window._taboola = window._taboola || [];

_taboola.push({

mode: 'thumbnails-c',

container: 'taboola-interstitial-gallery-thumbnails-49',

placement: 'Interstitial Gallery Thumbnails 49',

target_type: 'mix'

});

_taboola.push({flush: true});

Dr. Alain E. Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, watches new construction across Washington Avenue Extension at the college on Tuesday Sept. 27, 2011 in Albany, NY. ( Philip Kamrass/Times Union)

lessDr. Alain E. Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, watches new construction across Washington Avenue Extension at the college on Tuesday

... more

Albany Nanocollege CEO Alain Kaloyeros calls to an associate during the announcement of a new $500 million power electronics manufacturing consortium in the Capital Region at GE Global Research Tuesday July 15, 2014, in Niskayuna, NY. (John Carl D'Annibale/Times Union archive)

lessAlbany Nanocollege CEO Alain Kaloyeros calls to an associate during the announcement of a new $500 million power electronics manufacturing consortium in the Capital Region at GE Global Research Tuesday July

... more

Alain E. Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, on Tuesday June 26, 2012 in Albany, NY.(Philip Kamrass/Times Union archive)

Alain E. Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, on Tuesday June 26, 2012 in Albany, NY.(Philip Kamrass/Times Union archive)

Photo: Philip Kamrass

Sign on the ZEN Building at the SUNY Polytechnic Institute campus on Friday, Sept. 23, 2016, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union archive)

Sign on the ZEN Building at the SUNY Polytechnic Institute campus on Friday, Sept. 23, 2016, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union archive)

Photo: Will Waldron

SUNY Polytechnic Institute Campus on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union archive)

SUNY Polytechnic Institute Campus on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union archive)

Photo: Will Waldron

SUNY Polytechnic Institute Founding President and CEO Alain Kaloyeros, right, walks to Albany City Courthouse for his arraignment on state charges on Friday morning, Sept. 23, 2016, in Albany, N.Y. (Will Waldron/Times Union archive)

lessSUNY Polytechnic Institute Founding President and CEO Alain Kaloyeros, right, walks to Albany City Courthouse for his arraignment on state charges on Friday morning, Sept. 23, 2016, in Albany, N.Y. (Will

... more

Click through the slideshow to see the people indicted in the Buffalo Billion scandal.

Dr. Alain E. Kaloyeros, senior vice president and chief executive officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, resigned after been charged in September 2016 with federal wire fraud related to the alleged rigging of bids in favor of two upstate development firms. Kaloyeros was also charged on the state level with bid-rigging related to the development of a SUNY Poly dormitory.

Kaloyeros stands across from new construction on the other side of Washington Avenue Extension at the college on Tuesday Sept. 27, 2011 in Albany, NY. ( Philip Kamrass / Times Union)

less

Click through the slideshow to see the people indicted in the Buffalo Billion scandal.

Dr. Alain E. Kaloyeros, senior vice president and chief executive officer, College of Nanoscale Science and

... more

Photo: Philip Kamrass

Joseph Percoco, a former aide to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, arrives at federal court as the jury continues to deliberate in his corruption trial, Monday, March 5, 2018, in New York. Prosecutors say Percoco solicited over $300,000 in bribes from the businessmen who needed help from the state. A defense lawyer says Percoco never took a bribe. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

less

Joseph Percoco, a former aide to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, arrives at federal court as the jury continues to deliberate in his corruption trial, Monday, March 5, 2018, in New York. Prosecutors say Percoco

... more

Photo: Mark Lennihan

Todd Howe was a long-time Cuomo friend who in September 2016 pleaded guilty to multiple felonies, including several related to his role of bagman in schemes involving the exchange of cash from developers in exchange for official favors from former top gubernatorial aide Joe Percoco.

who was supposed to be the government's star witness in the bribery trial of Joseph Percoco, a former top aide to Democratic New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. In the weeks before the Percoco trial, it came to light that Howe tried to improperly recover the cost of a fancy Manhattan hotel room from a credit card company after signing an agreement not to commit any more crimes. (Will Waldron/The Albany Times Union via AP, File)

lessTodd Howe was a long-time Cuomo friend who in September 2016 pleaded guilty to multiple felonies, including several related to his role of bagman in schemes involving the exchange of cash from developers in

... more

Steven Aiello, executive vice president of Syracuse-based COR Development, was charged with conspiracy to commit honest services fraud.

Aiello was a co-defendant with Joseph Percoco in a corruption trial. Here, he arrives at federal court, Thursday, March 8, 2018, in New York. Jurors had announced on Tuesday that they were deadlocked but the judge asked them to return to deliberate in the trial of four businessmen. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

lessSteven Aiello, executive vice president of Syracuse-based COR Development, was charged with conspiracy to commit honest services fraud.

Aiello was a co-defendant with Joseph Percoco in a corruption trial.

... more

Louis Ciminelli, CEO of Buffalo-based development company LPCiminelli, was charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud. The charges stem from an alleged bid-rigging scheme involving Buffalo Billion-funded development.

Times Union staff photo by Paul Buckowski --- Louis Ciminelli, chairman and CEO of LPCiminelli, takes part in a panel discussion following the rally held by the Unshackle Upstate Coalition, in Albany, N.Y. on Tuesday, March 6, 2007.

lessLouis Ciminelli, CEO of Buffalo-based development company LPCiminelli, was charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud. The charges stem from an alleged bid-rigging scheme involving Buffalo Billion-funded

... more

Michael Laipple, an executive at Buffalo-based development company LPCiminelli, was charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud, but the charges were dropped on June 1, 2018.

Laipple, right, and his attorney Herbert Greenman, leave U.S. District Court in Buffalo, N.Y., Thursday, Sept. 22, 2016, after posting bond following an appearance in a corruption probe. The LPCiminelli executive was among eight people charged in a bribery and fraud case connected to Gov. Andrew Cuomo's efforts to revitalize the upstate New York economy. (AP Photo/Carolyn Thompson)

less

Michael Laipple, an executive at Buffalo-based development company LPCiminelli, was charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud, but the charges were dropped on June 1, 2018. Laipple, right, and his

... more

Photo: Carolyn Thompson

Kevin Schuler, a former executive at the Buffalo development firm LPCiminelli, pleaded guilty on May 18, 2018, to wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Kevin Schuler, right, leaves U.S. District Court in Buffalo, N.Y., Thursday, Sept. 22, 2016, after posting bond following an appearance in a corruption probe. The LPCiminelli vice president was among eight people charged in a bribery and fraud case connected to Gov. Andrew Cuomo's efforts to revitalize the upstate New York economy. (AP Photo/Carolyn Thompson)

lessKevin Schuler, a former executive at the Buffalo development firm LPCiminelli, pleaded guilty on May 18, 2018, to wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Kevin Schuler, right, leaves U.S. District

... more

Peter Galbraith Kelly Jr., who is known as "Braith," a former executive with Competitive Power Ventures Holdings, a Connecticut company pleaded guilty on May 11, 2018, to conspiracy to commit wire fraud: He admitted to defrauding CPV by misrepresenting that Percoco had obtained state ethics approval for his wife to work at CPV.

Kelly enters federal court, Wednesday, Jan. 24, 2018, in New York. He is a defendant, along with Joseph Percoco, in a case of alleged bid-rigging and bribery that reached some of the highest levels of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo's administration. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

lessPeter Galbraith Kelly Jr., who is known as "Braith," a former executive with Competitive Power Ventures Holdings, a Connecticut company pleaded guilty on May 11, 2018, to conspiracy to commit wire fraud: He

... more

Joseph Gerardi, an executive at COR Development in Syracuse, was found not guilty on the charge of conspiracy to commit honest services fraud.

An aerial image showing the outline for COR Development's Syracuse Inner Harbor project. (COR Development)

lessJoseph Gerardi, an executive at COR Development in Syracuse, was found not guilty on the charge of conspiracy to commit honest services fraud.

An aerial image showing the outline for COR Development's

... more

The Kaloyeros trial has a long list of potential witnesses. Click through the slideshow to see some of them. Albany NanoTech officials, from left to right, Brenda Birken, CNSE Vice President for Policy and Regulatory Affairs, Paul Tolley, CNSE Vice President for Disruptive Technologies, Steve Janack, CNSE Vice President for Marketing and Communications, Alain Kaloyeros, CNSE Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, John Loonan, CNSE Vice President for Finance and Fiscal Management, Pradeep Haldar, CNSE Acting Vice President for Green Energy Programs, Richard Brilla, CNSE Vice President for Strategy, Alliances and Consortia, Michael Fancher, CNSE Vice President for Business Development and Economic Outreach, and Robert Geer, CNSE Vice President for Academic Affairs, pose at the Albany NanoTech campus in Albany, NY on Thursday, Sept. 23, 2010. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

lessThe Kaloyeros trial has a long list of potential witnesses. Click through the slideshow to see some of them. Albany NanoTech officials, from left to right, Brenda Birken, CNSE Vice President for Policy and

... more

RPI President Shirley Ann Jackson walks with IBM?s Dr. John Kelly lll through the supercomputing center at the Rensselaer Technology Park in North Greenbush. Grant money sought to help fund a $125 million supercomputer was not awarded. Times Union staff photo by Lori Van Buren Lori Van Buren/TIMES UNION

lessRPI President Shirley Ann Jackson walks with IBM?s Dr. John Kelly lll through the supercomputing center at the Rensselaer Technology Park in North Greenbush. Grant money sought to help fund a $125 million

... more

Times Union Photo by Skip Dickstein -- Alain Kaloyeros speaks of a grant between the State of New York and IBM of $150 million dollars to establish a Center For Excellence at the State University at Albany's Center for Nanoelectronics at a gathering at the CESTM building in Albany, New York April 23, 2001. In the background are from left to right; Governor George Pataki, John Kelly III from IBM; and SUNYA Pres. Karen Hitchcock.

lessTimes Union Photo by Skip Dickstein -- Alain Kaloyeros speaks of a grant between the State of New York and IBM of $150 million dollars to establish a Center For Excellence at the State University at Albany's

... more

John Kelly III, senior vice president and director of IBM Research, addresses those gathered during an event at RPI on Wednesday, Jan. 30, 2013 in Troy, NY. The event was held for IBM and RPI to announce that IBM will provide a modified version of the IBM Watson system to the college for use by students and faculty. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

lessJohn Kelly III, senior vice president and director of IBM Research, addresses those gathered during an event at RPI on Wednesday, Jan. 30, 2013 in Troy, NY. The event was held for IBM and RPI to announce that

... more

Were you Seen at The College of Saint Rose Community of Excellence Awards luncheon honoring Marcia White, Michael Castellana and J. David Brown at Wolferts Roost in Albany on Thursday, June 16, 2016?

Were you Seen at The College of Saint Rose Community of Excellence Awards luncheon honoring Marcia White, Michael Castellana and J. David Brown at Wolferts Roost in Albany on Thursday, June 16, 2016?

Doug Grose at a Fort Schuyler Management Corporation board meeting on Monday, May 14, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski/Times Union)

Doug Grose at a Fort Schuyler Management Corporation board meeting on Monday, May 14, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski/Times Union)

Photo: PAUL BUCKOWSKI

Doug Grose CEO of NY CREATES, at SUNY Poly on Tuesday, May 1, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski/Times Union)

Doug Grose CEO of NY CREATES, at SUNY Poly on Tuesday, May 1, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski/Times Union)

Photo: PAUL BUCKOWSKI

Walter "Jerry" Barber Source: SUNY Poly

Walter "Jerry" Barber Source: SUNY Poly

Bob Blackman laughs with a friend. (Joe Putrock / Special to the Times Union)

Bob Blackman laughs with a friend. (Joe Putrock / Special to the Times Union)

Photo: Joe Putrock

From left, Alain Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, Mike Fancher, Vice President for Business Development and Economic Outreach, give Professor Yigal Komem, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Israel, and Nili Shalev, Israel's economic minister to North America , a tour of Albany Nanotech, on June 12, 2012 in Albany, N.Y. (Lori Van Buren / Times Union)

lessFrom left, Alain Kaloyeros, Senior Vice President and Chief Executive Officer, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, Mike Fancher, Vice President for Business Development and Economic Outreach, give

... more

(Times Union archive)

Mohawk Valley Edge President Steve DiMeo with Mohawk Valley EDGE employees at the Marcy Nanocenter site back in 2007. Six years later, the SUNY College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering has agreed to build the site.

less(Times Union archive)

Mohawk Valley Edge President Steve DiMeo with Mohawk Valley EDGE employees at the Marcy Nanocenter site back in 2007. Six years later, the SUNY College of Nanoscale Science and

... more

David Doyle, right, works at the War Room prior to the swearing-in ceremony.

David Doyle, right, works at the War Room prior to the swearing-in ceremony.

Photo: Michael P. Farrell

Dean Fuleihan, CNSE executive vice president fir strategic partnerships, speaks during the NanoCollege's Be the Change for Kid innovation awards on Thursday Sept. 26, 2013 in Albany, N.Y. CNSE awards school districts in the state with innovative awards for teaching math and sciences. (Michael P. Farrell/Times Union)

lessDean Fuleihan, CNSE executive vice president fir strategic partnerships, speaks during the NanoCollege's Be the Change for Kid innovation awards on Thursday Sept. 26, 2013 in Albany, N.Y. CNSE awards school

... more

Florence Nelson, a PhD candidate at the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, right, talks with Chris Borst, Assistant Vice President for Module Engineering, center, and Dean Fuleihan, Executive Vice President for Strategic Partnerships, left, at a high resolution transmission electron microscope at the schoo lon Wednesday Aug. 10, 2011 in Albany, NY. Students will be hired as paid interns for a new Silicon Valley company starting operations at the Albany complex. (Philip Kamrass / Times Union)

lessFlorence Nelson, a PhD candidate at the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, right, talks with Chris Borst, Assistant Vice President for Module Engineering, center, and Dean Fuleihan, Executive Vice

... more

From left, Professor Yigal Komem, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Israel, and Nili Shalev, Israel's economic minister to North America , get a tour of Albany Nanotech from Mike Fancher, Vice President for Business Development and Economic Outreach, on June 12, 2012 in Albany, N.Y. (Lori Van Buren / Times Union)

lessFrom left, Professor Yigal Komem, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Israel, and Nili Shalev, Israel's economic minister to North America , get a tour of Albany Nanotech from Mike Fancher, Vice President

... more

Robert Geer, the who as chief operating officer of SUNY Polytechnic Institute led the school's Utica campus, is stepping down Dec. 1 and will return to SUNY Poly's faculty. Source: Times Union archive.

Robert Geer, the who as chief operating officer of SUNY Polytechnic Institute led the school's Utica campus, is stepping down Dec. 1 and will return to SUNY Poly's faculty. Source: Times Union archive.

Brian Hannafin, vice president of corporate development at Danforth, at the Buffalo company's office at SUNY Poly's ZEN building. Source: Larry Rulison

Brian Hannafin, vice president of corporate development at Danforth, at the Buffalo company's office at SUNY Poly's ZEN building. Source: Larry Rulison

Andrew Kennedy, president and CEO of Center for Economic Growth presents the findings of a first-of-its-kind survey of the Capital Regions video game development cluster at the Tech Valley Center of Gravity Wednesday March 7, 2018 in Troy, NY. (John Carl D'Annibale/Times Union)

lessAndrew Kennedy, president and CEO of Center for Economic Growth presents the findings of a first-of-its-kind survey of the Capital Regions video game development cluster at the Tech Valley Center of Gravity

... more

Tom Louis is a former State Police senior investigator who retired in 2007. He is heading a police force being established as the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering of the State University of New York. (John Carl D'Annibale / Times Union)

lessTom Louis is a former State Police senior investigator who retired in 2007. He is heading a police force being established as the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering of the State University of New

... more

Thomas O'Brien

Thomas O'Brien

Photo: SUNY Poly

Tom Birdsey, CEO and President of EYP speaks at the ribbon cutting at The College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering(CNSE) of the University at Albany and Einhorn Yaffee Prescott(EYP) Architecture and Engineering PC of Albany at the the opening of a $3.5 million initiative that includes the opening of an Alternative Energy Test Farm and the development of a joint educational and workforce training program to prepare the professional who will design and operat the high-tech buliding of the 21st century at a ceremony at CNSE in Albany, New York December 14, 2009.

lessTom Birdsey, CEO and President of EYP speaks at the ribbon cutting at The College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering(CNSE) of the University at Albany and Einhorn Yaffee Prescott(EYP) Architecture and

... more

Alicia Dicks worked for National Grid before she took a job as president of Fort Schuyler Management Corp. She is currently CEO of The Community Foundation of Herkimer & Oneida Counties.

Alicia Dicks worked for National Grid before she took a job as president of Fort Schuyler Management Corp. She is currently CEO of The Community Foundation of Herkimer & Oneida Counties.

Photo: Community Foundation

Times Union staff photo by Paul Buckowski

Brenda Lubrano-Birken, General Counsel and Director of Legal Services for University at Albany, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, poses outside one of the clean rooms at the college in Albany, N.Y. on Monday, June 19, 2006. Birken has been elected to the National Board of Directors, and is also Corporate Secretary for the Alliance of Technology and Women.

lessTimes Union staff photo by Paul Buckowski

Brenda Lubrano-Birken, General Counsel and Director of Legal Services for University at Albany, College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, poses outside

... more

Kaloyeros' legacy as SUNY Poly leader is on trial

Albany

When historians look back and try to explain what went wrong at SUNY Polytechnic Institute, they might try to point the finger at Alain Kaloyeros, the local visionary who founded the Albany school and is facing a bid-rigging trial later this month in a Manhattan courthouse.

After all, Kaloyeros will be the star defendant in the case, along with executives from two upstate construction and real estate development firms that built SUNY Poly projects in Buffalo and Syracuse.

In the court of public opinion, Kaloyeros' legacy will be framed by the outcome of the trial, scheduled to begin June 18 in New York City.

But in reality, Kaloyeros' legacy was cemented 20 years earlier when the first building at SUNY Poly — the odd-looking, $12 million, 75,000-square-foot CESTM building — was built atop a sandy plot on Fuller Road.

Today, SUNY Poly's Albany campus, home to the Colleges of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, has grown to 1.5 million square feet and is home to thousands of researchers and scientists with an estimated $24 billion in private and public sector investment over the decades. The school also has a Utica campus.

Photo: Jeff Boyer/Times Union

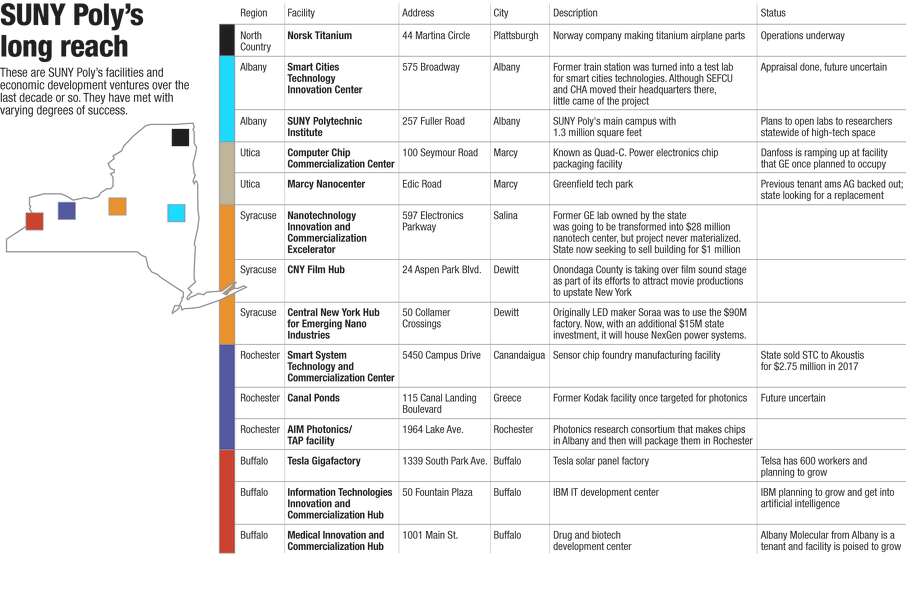

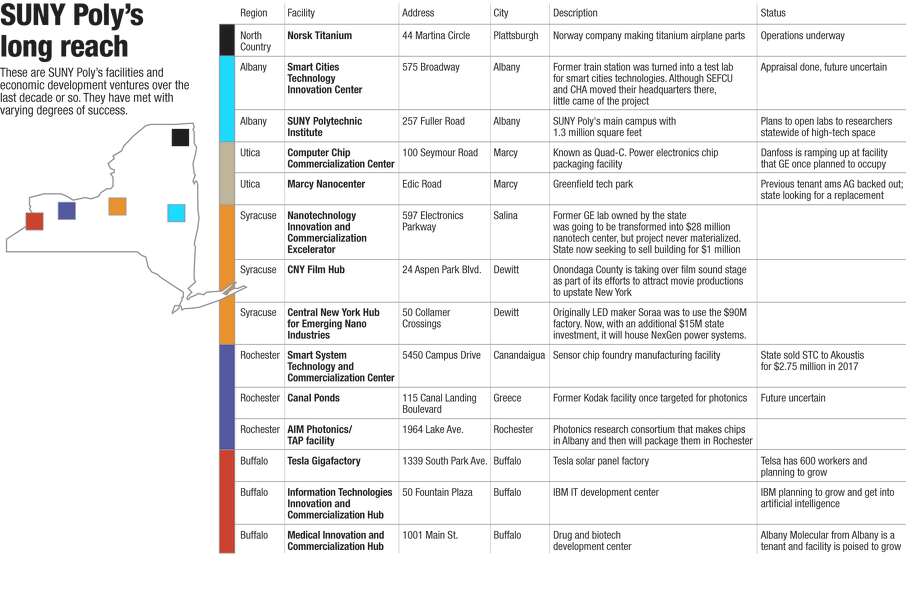

SUNY Poly's empire extends across the state.

SUNY Poly's empire extends across the state.

Both GlobalFoundries and IBM do their most important computer chip research in Albany, along with their top suppliers and research partners like Samsung.

Even if things don't go well for Dr. K,, as Kaloyeros is known, SUNY Poly or Albany Nanotech, as it is also referred to across the globe, will still stand.

"I'm not sure the region understands what an outstanding, international facility it is," said Georgetown University professor Charles Wessner, who recently published a book on the Capital Region's semiconductor economy. "You have a unique facility up there, and it's also important on a national level."

Wessner's book, which he co-authored with semiconductor trade expert Thomas Howell, was published in April.

What has muddied the waters has been SUNY Poly's ventures in other parts of the state, some of which became the focus of the criminal trial against Kaloyeros, who is accused of tailoring SUNY Poly's procurement process to favor two contractors, LPCiminelli of Buffalo and COR Development of Syracuse. Executives at the two firms were also big campaign donors to Gov. Andrew Cuomo, although Cuomo has never been accused of any wrongdoing.

Kaloyeros has maintained his innocence. He declined to speak for this story.

In their book, Wessner and Howell believe that for the past several years SUNY Poly's efforts have been overshadowed by the Kaloyeros case, leading some of SUNY Poly's projects to stall and others to fall apart.

"Regardless of what may be failures of judgment on the part of some individuals, the fact remains that (the Colleges of Nanoscale Science and Engineering) — and to a greater degree, SUNY Poly — have proven to be important institutions in the development and ongoing support for the advanced manufacturing and semiconductor development ecosystem in the state and nation," the book states in a section about Kaloyeros' legal troubles.

Wessner, who spoke to the Times Union last week by phone, said it was important that SUNY Poly recently hired Doug Grose to lead the institution's economic development and commercial research partnerships in Albany and across the state. A permanent president who will oversee SUNY Poly's academic operations will also be hired.

Grose is a former CEO of GlobalFoundries who worked for a long time at IBM, which was the first company to take space at SUNY Poly. Wessner and others who follow the semiconductor industry have argued that Kaloyeros must be replaced by someone with computer chip industry experience and not be merely an academic. Kaloyeros spanned both industries. In addition to working at IBM and GlobalFoundries, Grose also worked briefly at Albany Nanotech when it was still part of the University at Albany.

"I can't think of a better person," Wessner said of Grose. "He has the industry experience that you need. Now they've restored leadership."

When Kaloyeros left SUNY Poly following his September 2016 arrest, Cuomo put Howard Zemsky, the state's top economic development official, in charge of SUNY Poly's economic development projects and research partnerships. Zemsky hired Bob Megna, the former state budget director, to temporarily do the job that Grose will soon undertake. Zemsky says when his state agency, Empire State Development, took over at SUNY Poly, it was able to bring a lot of expertise in real estate, finance, contracts negotiation and accounting that SUNY Poly as a school may not have had at its disposal.

Plus Zemsky and his staff examined every SUNY Poly project and renegotiated those that needed changes and sold off properties that weren't a good fit. Zemsky and ESD also got Cuomo and the Legislature to approve a $207 million fund to stabilize SUNY Poly's finances.

The result, he said, has been that many of SUNY Poly's various projects across the state may be better off than they were before ESD took control.

"I'm proud of the work that ESD has done," Zemsky said. "We went from being involved on a Tuesday to being in charge on a Wednesday, and we applied all of our skills across the board at ESD."

Although some could argue that it was SUNY Poly's expansion from Albany to across upstate following Cuomo's 2010 election that led to its downfall, Zemsky says the idea of exporting the SUNY Poly model to other cities is valid.

"It was the governor's intention to seed the upstate economy with 21st-century industries to help offset the decline of manufacturing across large portions of upstate New York," Zemsky said. "I think we are continuing to build a robust ecoystem of high tech industry."

F. Michael Tucker, the former CEO of the Center for Economic Growth in Albany, says high-tech economic development is the hardest to get done because the industry is so volatile.

"There are a multitude of risks associated with any development project," Tucker said. "With larger projects, especially those in the technology arena that involve multiple public and private partners, the obstacles to success are even greater."

But Tucker says even though some projects fail, SUNY Poly's research labs are always working on the next generation technologies that will create breakthrough industries.

"While projects don't always work out as well as planned, state economic development initiatives and private partnerships have contributed to strengthening the Capital Region's position as an emerging technology center and have helped to create a nimble environment where a project can successfully be reoriented and refocused," Tucker said.

lrulison@timesunion.com • 518-454-5504 • @larryrulison

https://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Kaloyeros-legacy-as-SUNY-Poly-leader-is-on-trial-12979088.php

https://www.timesunion.com/local/article/Kaloyeros-legacy-as-SUNY-Poly-leader-is-on-trial-12979088.php