Punjabi Lane in Shillong on Tuesday. (Photo: Abhishek Saha)

Punjabi Lane in Shillong on Tuesday. (Photo: Abhishek Saha)

“FOR ALL of us living in Punjabi Lane, our Punjabi identity is the foremost thing, rather than a religious identity. Ever since trouble started in this area, we are together with our Sikh brothers,” says Sonu Chadha, a Christian Punjabi, as his friend ties a turban on him and they rush to the gurdwara to listen to a visiting Sikh leader from Punjab.

The gurdwara is located on the second floor of a school building, a church stands next to it, while a few metres away is a temple where space is also kept aside for followers of a sub-sect of Sikhism called Udasi.

However, it is this strong regional identity uniting residents of Punjabi Lane, overarching other differences, that makes its divide with the city’s majority Khasi population sharper.

Since clashes erupted following an altercation between a Khasi bus driver and a woman from the Punjabi Lane on May 30, the locality next to Shillong’s commercial hub and its largest traditional market place of Iewduh, or Bara Bazaar, has been under almost continuous curfew, except for seven hours on June 3. Security personnel chase away anyone trying to enter Punjabi Lane, or those trying to get out despite curfew.

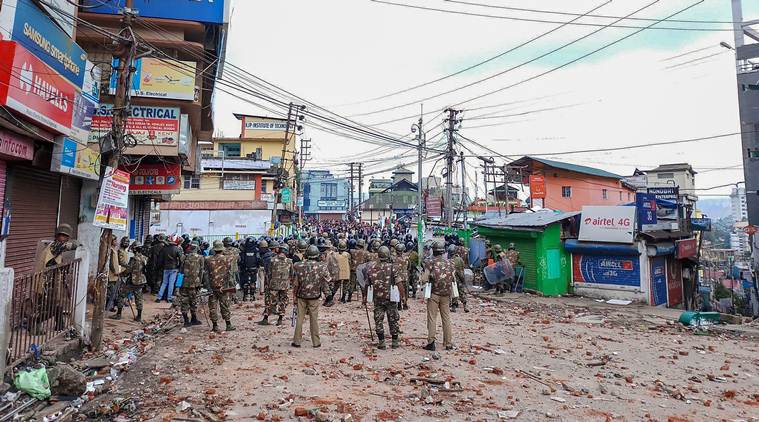

Security forces on duty in Shillong. (PTI/File)

Security forces on duty in Shillong. (PTI/File)

On Monday morning, a group of anxious men sat outside their homes discussing the stone-pelting and teargas shelling that had been on all night till 5 am. In the midst of her household chores, Nisha Kaur, in her mid-20s and a mother of two, says, “Life in Punjabi Lane is fine but there have been worries since the violence began.”

The original settlers in Punjabi Lane were Sikh Dalits brought here by the British to work as scavengers and sweepers. Himadri Banerjee, former professor of Indian history at West Bengal’s Jadavpur University, who has done extensive work on the history of Sikhs in the Northeast, says, “There is no fixed date as to when the Dalit Sikhs came. They possibly arrived with a British Army contingent that moved from Punjab to Shillong in the last quarter of the 19th century.”

The original settlers in Punjabi Lane were Sikh Dalits brought here by the British to work as scavengers and sweepers. (Express Photo/Abhishek Saha)

The original settlers in Punjabi Lane were Sikh Dalits brought here by the British to work as scavengers and sweepers. (Express Photo/Abhishek Saha)

Now there are 350 Sikh families here, apart from 20-odd families that have converted to Christianity, a couple of Hindu families, and the Udasi sect followers.

However, Punjabi Lane itself appears frozen in time — no more than a congested cluster of wooden houses with tin roofs, with a road running through it. It was a bus blocking a water tap on this road that sparked off the clash, leading to the violence.

The colony is also struggling to rid itself of the tag of ‘Sweepers’ Lane’, that remains attached to it. Community members say they have moved on, and that youngsters no longer want to do the jobs their forefathers did.

Gurjeet Singh, the general secretary of the Gurdwara Committee of Punjabi Lane since 1995, says, “Our children are educated. We want to progress.”

Around 350 families live in ‘Punjabi Lane’. (Express photo by Abhishek Saha/File)

Around 350 families live in ‘Punjabi Lane’. (Express photo by Abhishek Saha/File)

But the violence with the Khasis could cloud that. Hari Singh, 55, holds up a picture of a group of Sikh men from the 1950s posing in Punjabi Lane, and says, “I was born and brought up here. I have seen minor skirmishes, but this time, the violence seemed more aggressive. They are bent on evicting us from this locality immediately.”

For at least three decades, sections of society and political organisations have been demanding that residents of Punjabi Lane be settled in some other area — the primary argument being that a prime commercial area shouldn’t hold a residential locality. There have been brawls earlier too between residents and Khasis passing through the area.

Gurjeet Singh says the “market area” logic does not stand as there are many commercial areas where Khasis live too. He also cites two orders by the ‘Syiem’ or “chief” of Mylliem to counter claims that the residents of Punjabi Lane are “illegal” settlers. Mylliem is one of the 54 traditional administrative territories under the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council.

Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma. (PTI Photo/ File)

Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma. (PTI Photo/ File)

“The syiem of Mylliem, who is popularly referred to as ‘king’, has power over our land. The syiem gave us this land and we have two documents to prove this, a 1954 agreement and another in 2008. The 2008 document says this land was given to us prior to 1863. The agreements ‘recognise’ and ‘respect’ our settlement. How are we illegal?”

But Donald Thabah, general secretary of the powerful Khasi Students’ Union, warns protesters won’t stand down. Describing the current violence as “a public revolution”, he says, “The protests will not stop unless the illegal setters are removed from the area. People’s anger and frustration are coming out.”

While support has poured in for Punjabi Lane residents from Sikh organisations in India and abroad, as well as the Akali Dal and Punjab government, they fear that this time they may lose their homes.

On Monday, Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma announced that a high-level committee would examine all the relevant records on relocating them and suggest “practically feasible solutions”.

Others fear their ties with Khasi friends and acquaintances may have been strained. Sunny Singh, around 30 and a bank employee, says, “Most of my colleagues are Khasis and we work well together. They have been asking about my well-being… But I wonder if this will affect our relations.”

Shopkeeper Ajay Singh is apprehensive about the raised eyebrows he might meet now when he introduces himself as “a resident of Punjabi Lane, Bara Bazaar”.

Lamenting their “status”, Gurjeet Singh says, “Our Sikh community has made great sacrifices in India’s freedom struggle. Even today, at the border, Sikh soldiers stand at the front. But here we are third-class citizens.”