The cartoonist Nick Drnaso has produced an extraordinary – and extraordinarily upsetting – novel. His first book, Beverly, a collection of interrelated short fiction published in 2016, announced him as a writer of keen attentive-ness to the present moment, offering a fresh, kaleidoscopic view on contemporary life that called to mind the films of Todd Solondz or the writing of George Saunders; Beverly won an LA Times book prize.

His second book, which Zadie Smith has called “a masterpiece”, is, appropriately, twice as good. And given that Drnaso is only 29 this year, it offers a rather formidable calculus by which to anticipate the trajectory of his artistic development.

Drnaso was born in the Chicago area, the setting for his first book. He opens this story there as well, with a homey scene of a homely young woman cat-sitting for her parents. Her sister, Sandra, arrives for a brief visit, reminiscing about their parents, asking about her boyfriend, and soliciting some help with a crossword puzzle. Sandra mentions an urban bus trip she took by herself when she was 19 that opened her eyes to the dangers of the world and asks her sister if she’d like to take a bicycle vacation along Lake Michigan later that summer. The two make a half-promise to do so – “That sounds great. Get out of the city. Get away from the internet,” her sister jokes – and Sandra leaves. It will be the last time Sandra sees her sister.

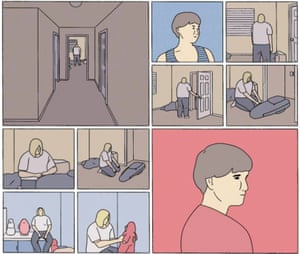

From there, we are catapulted to a town in Colorado, where Calvin, an Air Force soldier (although he is addressed by his fellow soldiers as “airman”, he never sets foot on a plane), meets his childhood friend Teddy in the airport. He’s offering to put Teddy up for a while because, as we learn, Teddy’s girlfriend went missing a month before. Teddy, a quiet man-child who peers through shoulder-length blond hair, is shell-shocked and has little to say; Calvin’s overtures at rehydrating some flow of camaraderie between them via fragmentary memories of school and a mixtape Teddy made for him years before go nowhere. Calvin drives Teddy to his bland strip-mall encircled condominium townhouse, a home of dispiriting banality that suits the earnest vapidity of his conversation. Granting Teddy use of the room that Calvin’s daughter occupied until his recent separation from his wife, he clears stuffed toys away for Teddy to lie down on a single mattress, then excuses himself to go to work.

These two scenes and locales set up the story for the next year and roughly 200 pages that follow, which I won’t spoil, other than to say a video of an apparent atrocity plays a central role. Teddy is, of course, the boyfriend of the cat-sitting girl, whose name, Sabrina, echoes through the remainder of the book with an ever-increasing resonance and horror. With Sabrina vanished, Drnaso allows himself to think the unthinkable; one’s worst fears about the disappearance of a loved one are directly addressed and, in most cases, grimly and grittily realised. He at no point lapses into cliche or sensationalism; the book is dispassionately presented – I was reminded of Flaubert’s advice to write “scientifically” – and feels as dislocatingly real as one imagines real life might be under similarly dreadful circumstances.

What’s most curious and, ultimately, valuable about this book is that it is not a crime story; it’s a perspicacious and chilling analysis of the nature of trust and truth and the erosion of both in the age of the internet – and especially, in the age of Trump.

Sabrina’s story develops from the uncertain, unpredictable emotions of lived experience to the micro-paranoias of clickbait with a speed and, worst of all, a familiarity that is blood-curdling.

The malleability of recorded evidence, the chatroom dissection of apparent contradictions in video and news footgage and the airless metastasis of radio and online conspiracy theories all dismantle the reality of the characters with a grotesquerie and a speed that’s become unsettlingly customary in our age of mass shootings and terror attacks. Drnaso sets out his arguments expertly, even invisibly, weaving a history lesson on conspiracy theories from 9/11 to deniers of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting directly into the story itself.

Again, though it is very carefully constructed – rhymes and echoes of action are spaced throughout the story like landmines. No line of dialogue is wasted – Drnaso’s story doesn’t feel “plotted”, but as though it is happening just as one feels life does, even those moments of great emotion, such as a character’s unimaginable anguish and helplessness in the face of uncertainty, or the clinical interest one can take in the prurient details of a reported crime as a distraction from the painful realities of one’s own existence.

Ultimately, certain contradictions in the narrative subtly invite the reader to theorise about Sabrina’s fate, incriminating the reader and in the very process driving the story itself. The effect is all too nauseatingly routine. And the fact that the very idea of “believing one’s eyes” is under attack by digital technology that can produce confected videos of such verisimilitude that it’s undetectable, should terrify us all. “Get away from the internet,” indeed.

But at least believe what you see in Drnaso’s book, because it’s a story told entirely in pictures. And you will find yourself looking carefully, trying to piece it all together. I found the experience deeply unnerving. Most especially because Sabrina is a book that looks right back at you.

Chris Ware’s Monograph is published by Rizzoli.

• Sabrina is published by Granta. To order a copy for £14.44 (RRP £16.99) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.