A clutch of bedraggled fancy dress characters lie in wait for visitors to Times Square on a late weekday morning, hustling for tourist dollars in return for a souvenir picture.

Superheroes and Muppets compete with a collective of Disney mice, a topless woman wearing a red, white and blue feathered headdress, and her slightly more modestly-dressed friend, who has added a patriotic bra and the letters N and Y in white greasepaint on her butt.

A bronze statue of George M Cohan, the impresario-songwriter who wrote ‘Give my regards to Broadway’ stares past them down the long stretch of possibly the most famous street in the world, beyond an eight-story neon altar to advertising, toward the improbably slender Flatiron building, 23 blocks south.

Here is modern Broadway at the most grimly commercial point of its 13-mile journey, slicing along the length of Manhattan. Where, a century earlier, the deluxe Rector’s restaurant once prepared lobster ‘sixteen different ways at a dollar apiece”, Bubba Gump Shrimp Co now serves its seafood to New York’s visitors with a “boat size bucket of fries” on the side.

The Great White Way – nicknamed in the early 1900s for its dazzling electric lights – feels dispiriting here at its epicentre in the raw light of day. Fran Leadon, the author of a new history of the street that tells the story of modern America, almost visibly recoils from a fancy dress Batman as we pick through the aimless herd.

Broadway is still global shorthand for bright lights, big city – and even though modern Times Square is underwhelming by day, it is a garish explosion at night. Right now, global stars including Bruce Springsteen, Denzel Washington and Glenda Jackson compete with musical revivals of My Fair Lady, Carousel and Hello Dolly! as well as a newly-arrived Harry Potter extravaganza.

The spectacle is gaudy, but sits well in the tradition of the theatre district, which Leadon writes in Broadway; A History of New York City in Thirteen Miles always provided a “delirious exaggeration of American culture”. This is the street that drove America forward – the Path of Progress as it expanded north, powered by showmanship and illusion.

“There is a mythology about Broadway that we take for granted,” Leadon says. “The Great White Way, the crossroads of the world, the theatres, ticker tape parades, all these public displays. I had always thought that mythology came from the street, from all the things that were there and the things that had happened there.

“I think what I have concluded is that it was the opposite – which is much more interesting – this community, especially of business types, kind of invested in this mythology. They wanted the street in New York, in the country, to be powerful, to be magical, to be creative, and everything that followed was fulfilling that desire to have it be this mythical place.”

Starting at the southern tip of Manhattan, like the island’s spine, Broadway has held the city together and sometimes been its fault line. It has witnessed riots, police beating crowds of protestors, the symbolic downfall of a colonial monarch and the rise of the first US president.

Wild, brawling men and outrageous, over-inflated showmen have been venerated there, office workers have greeted presidents, war heroes, sports stars and astronauts with signature ticker tape parades.

“From the beginning, it was the economic engine of the city, it was the thing that was pointing the way towards the city’s development,” Leadon said. “Broadway was always the place where things happened first: the first theatre; the first really big hotel; all the main churches. It was originally where all the big mansions were, downtown. It was always the big incubator for the city.”

The 80-feet wide muddy, early 17th century route to drive livestock through the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam was named Brede Wegh – Broad Way – and when the British took over, it was Anglicised and conjoined to become Broadway.

It remained a filthy mess, hogs foraging in the street, Caribbean pirates in the taverns. Less than a mile long, and, from an early stage, a physical expression of inequality – the east side developed by artisans and tradesmen was known as the shilling side, and the west, owned by Trinity Church, was the wealthy dollar side.

“Since it was the main gathering place in the city, it was where everything came together, so the wealthiest people in the country, but also the poorest and the native born, old Dutch families, but also the newer immigrants, slave-owner and slave,” Leadon said. “It’s always been representative of this gap between wealth and destitution and as the city developed, it just got wider and wider and wider, but it was there from the very beginning.”

The panic of 1837, a financial crisis which triggered recession, led to crowds of destitute men and women lining up for bread and firewood. Today, the midtown stretch is still a haven for homeless people, slumped on sidewalks and public squares.

Broadway charts the American story. When General George Washington sailed into New York in 1776, he took over an almost abandoned city after British forces fled. After the first copies of the Declaration of Independence reached New York, on the night of 9 July, Washington read it aloud to his troops, who rushed down Broadway to Bowling Green. “Ropes were thrown around the gilded statue of George III and, following a series of hopeful cracking noises, king and horse hit the ground.” The statue was hacked up and its lead melted down to make bullets to use against the British redcoats.

In 1790, as the first president of the United States, Washington briefly moved into 39-41 Broadway, but by the time Government House was finished, in 1791, New York had lost the capital to Philadelphia.

Fears of inferiority drove progress and sent Broadway extending north, in spite of the hard-to-tame marshlands, eventually diverted underneath modern day Canal Street. Leadon said the idea was: “ ‘If we spruce up the city a little bit, maybe we can look like Philadelphia … we need better architecture to start to compete with Philly and Boston and become the main American metropolis’.”

Money and grand homes shifted north, fashionable stores followed, offices and hotels came in behind and pushed the theatres north, too.

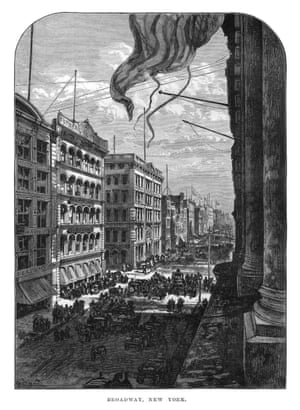

By the time AT Stewart & Co opened a “marble palace” of a dry goods store in the 1840s, Broadway had seized commercial dominance as the place to get the first pick of Paris fashions arriving by ship from Europe. Shopping and promenading became a cultural phenomenon.

The visiting Charles Dickens arrived on Broadway and was dazzled, writing: “We have seen more colours in ten minutes, than we should have elsewhere is as many days. What various parasols! What rainbow silks and satins!”

The 1850s brought a hotel boom – the St Nicholas was celebrated as the largest and most elegant in the world – but the fashionable advance was also accompanied by prostitution, and violent gangs who fought epic battles. William Poole, immortalised as Bill the Butcher – champion boxer, butcher, rightwing anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant politician – died a lingering death after he was shot in a hotel bar brawl. Broadway drew crowds of 100,000 to see an open hearse drawn by four white horses, cloaked in black, with white plumes on their heads lead a procession of 4,000 people to his Brooklyn burial ground.

By the 1870s Central Park was nearing completion – built as a haven from noise and overcrowding, an answer to the great green spaces of European cities, such as London’s Hyde Park. And Broadway took off north again – the sixth and seventh miles up to 106th Street becoming more like a wide European boulevard. “By then,” Leadon said of the expanding metropolis, “they are thinking, ‘we need to look like Paris, we need to compete with the European cities’... Philadelphia was long ago vanquished and they were trying to compete with London and Paris.”

Electric light arrived in 1880, and the first electric billboard in 1892, at the site where the Flatiron would spring up a decade later. Probably the most audacious early ad was at 38th Street in 1910 – 72ft high and 90ft wide and “inspired by the long-running Broadway hit Ben-Hur, featured a moving chariot race complete with galloping horses and cracking whips, animated by an ingenious sequencing of 20,000 incandescent bulbs that flashed on and off 2,500 times a minute.”

The most enduring, unique landmark to Broadway’s heyday, built in 1902, still stands today, like an ocean-going liner at the narrow point where Broadway meets Fifth Avenue at 23rd Street. The ‘freak building’ as it was described, better known as the Flatiron, was a futuristic skyscraper, built from steel, clad in limestone, brick and terracotta tiles. It was modelled after the giant American Imperialism structures of the Chicago World’s Fair, but madly compromised by its sharply triangular plot. It became known as hurricane corner as winds played havoc with hats and women’s hemlines. Cops arrested men who gathered to gawp, and a magistrate ruled in the case of a French tourist, that “two minutes is a reasonable time ... and you can use your eyes but at the end of that time you must move on”.

By miles 12 and 13, Leadon says, “the past is a little closer to the surface”. Farmland was not really developed until the subway got there in the early 20th century; Inwood Hill Park at the top of Manhattan still has overgrown foundations of old ‘Gilded Age” mansions in the woods. John F Seaman’s 19th century marble house had 25 rooms, an observatory and a swimming pool. The entry gatehouse was a scaled down Arc de Triomphe. “Today almost nothing is left,” he writes, but “tucked behind an auto body shop on the west side of the street between 215th and 218th streets, Seaman’s Arc de Triomphe still peers out at the street, covered with graffiti and gradually succumbing to the weight of time”.

Today, the pattern of flatten and replace goes on. As he walked north from Flatiron, Leadon gasped as he reached 28th Street and saw another building being razed. “That’s the last vestige of the old Broadway of the 70s and 80s, marginal discount stores full of trinkets, wig stores buying and selling human hair. Weird, weird stuff.”

He sounds regretful, almost as if a tiny part of his book is already out of date. But as he records, on Broadway it was always this way; money drives everything forward. As journalist Junius Henri Brown put it in 1868: “Broadway is always being built, but it is never finished.”