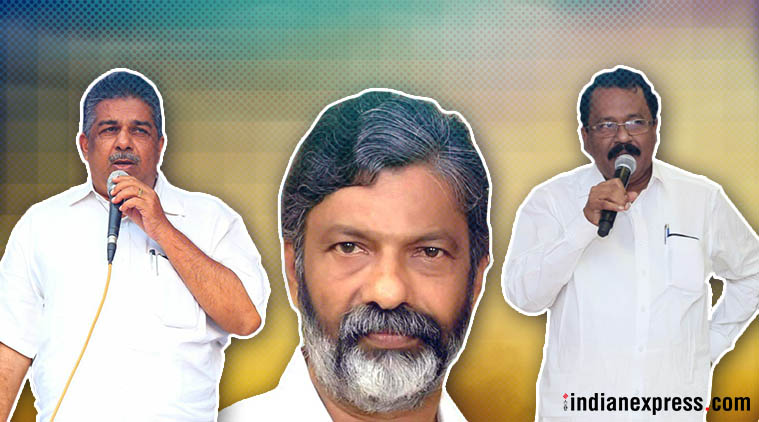

(Left to right) CPM candidate Saji Cherian, Congress’s D Vijayakumar and PS Sreedharan Pillai from the BJP were in the contest in Kerala’s Chengannur bye-election.

(Left to right) CPM candidate Saji Cherian, Congress’s D Vijayakumar and PS Sreedharan Pillai from the BJP were in the contest in Kerala’s Chengannur bye-election.

Rarely in an election, people start celebrating the victory of a candidate even before the votes are counted; but it happened at the Chengannur bye-election in Kerala, where not only the ruling CPM-led Left Democratic Front (LDF) thought its win was a done deal, but the Congress-led opposition willy-nilly conceded it too.

the LDF and the CPM were proved right, but were surprised by the massive margin of victory – more than 20,000 votes. The opposition candidate, a local functionary of the Congress, appeared to be a bad loser and hinted at the lack of enthusiasm in his party and weaknesses in its electioneering. His party leaders said that the CPM victory was because they communalised the campaign, a charge that was far from true.

The despondency of the Congress candidate and the unreasonable excuse that the party cited for its shameful defeat betrayed a dangerous vulnerability that may push it into further trouble. Plagued by several allegations of nepotism, misuse of power, corruption and failing law and order, the incumbent LDF government, particularly Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, hadn’t had a great ride so far and hence the Congress had the best opportunity to win.

But it not just failed, but failed miserably.

An occasional bypoll doesn’t foretell anything, but this one should seriously worry Congress because it’s the continuation of a trend that it has landed itself in 2016: the party’s fortunes being eaten away by a rising BJP.

In the 2016 Assembly elections, except in constituencies with sizeable representation of minorities (Christians and Muslims), the party lost very badly. In fact, in the Hindu-majority areas it lost 26 seats. In all these places, BJP’s vote-share rose sharply. In districts such as Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Thrissur and Palakkad, where it had a reasonably good vote-bank, the party looked like a shadow of its former self, and obviously were routed.

In the southern districts of Thiruvananthapuram, which incidentally has about 67 per cent Hindus as against the state average of 55, and Kollam, the LDF won 20 out of the 25 seats. The only districts that protected its Congress-led rival United Democratic Front (UDF) from a complete washout were Malappuram, Ernakulam and Kottayam where Muslims and Christians form the majority.

Obviously, in the non-minority areas, the Congress and the UDF lost a big chunk of its traditional vote bank and probably, even the fence sitters who ensure that the LDF and the UDF get only alternating chances to be in power. And this erosion has happened because of the BJP. BJP’s rise is commensurate with the UDF’s, or rather the Congress’s, fall.

In 2011, the UDF came to power with 45.89 per cent of the vote-share as against the LDF’s 44.99. The BJP-front’s (NDA) vote-share then was a modest 6 per cent, a little higher, not substantially more, than what it got in five years ago. But in 2016, its vote-share rose to 14.65 while the LDF remained more or less where it was in 2011 with a share of 43.42 per cent. However, the UDF nosedived to 38.8 per cent.

Clearly, while the BJP rose, nothing much happened to the LDF while the UDF lost its limbs and power.

While from 2006 to 2011, a marginal rise of the BJP’s vote-share didn’t affect the UDF as much as it did the LDF, from 2011 to 2016, the UDF and the Congress had been devastated – most probably because of the post-Modi phenomenon. Clearly, by 2016, a number of the erstwhile UDF voters in the Hindu-majority districts saw the BJP as a more attractive alternative and the former either didn’t know the earth moving under their feet or didn’t know how to check the erosion. The result in Chengannur, where the BJP candidate was a close third, has reinforced this trend – a big chunk of the UDF votes have migrated to the BJP and have decided to stay over there.

For the Congress and the UDF, this should be a nerve-racking proposition because unless the BJP suffers a major national collapse both in terms of image and power, it’s hard to wrest these votes back. Backed by numbers, the CPM all along knew that an electorally stronger BJP can destroy the Congress and the UDF, but will not be strong enough to dent its chances. Probably for the same reasons, the CPM has been actively encouraging the BJP as its rival for the last few years, even when it was only a third player, while the Congress neglected it and took on the CPM.

CPM’s strategy of inflating the BJP’s political space seems to have worked. If the BJP is able to retain its vote-share, it will be hard for the Congress and the UDF to come back in the next elections and Kerala may see a back-to-back left rule in 2021.

The debacle of the Congress is its own making because it failed to realise that the BJP was feeding on its soft tissue. It either failed to analyse the numbers and acknowledge that the upper caste and upper class Hindu votes were highly unreliable, or devised a wrong strategy to address it.

Many critics feel that it’s the latter that has done them in because according to them, the Congress tried to adopt a “soft Hindutva” strategy to woo back the unreliable Hindu votes while the CPM took the BJP head on. Simultaneously, they also tried to woo the minority votes that have eluded them for long. Even in Chengannur, critics of the Congress allege that the choice of the candidate was driven by this “soft Hindutva” strategy. In hindsight, the detractors seemed to be right – the Congress hasn’t taken on the BJP as vehemently as the LDF did, and hence a lot of its supporters didn’t have any qualms in shifting their allegiance.

There’s one more worrying factor that is likely to destabilise the UDF – the increasing affinity of the minority votes towards the CPM and the LDF. In fact, the LDF has already won four out of the five seats in the Christian dominated Pathanamthitta district in 2016, and in Chengannur, the CPM candidate couldn’t have managed such a margin without the support of the minority votes (Christian).

Clearly, the Congress and the UDF are in deep trouble – not only in terms of losing out to the BJP, but also because of the lack of a potent strategy and charismatic leadership. The party is faction-ridden with at least four of the leaders wanting to be in control. The leaders that the High Command in Delhi patronise have no electoral following and are at best disruptive in the party affairs. The only leader with a mass following – former Chief Minister Oommen Chandy – has now been made a national leader and the state unit is saddled with Ramesh Chennithala, the present opposition leader, who neither has the popularity or capacity to reverse the party’s fortunes.

Unless the party comes up with a super charismatic leader – a person who can inspire the voters at least in the erstwhile Travancore areas – and decides to take on the LDF and the BJP with equal vigour, the Congress will be in acute crisis.

And if the crisis continues for long, the damage will be irreversible. A selfish CPM will be happy about such a prospect because it will protect them from extinction in India, but in the process they would have irreversibly damaged the democratic secular fabric of the state for which the Congress had a inalienable role.