As a fantasy lover, I can barely remember a time when I wasn’t aware of JRR Tolkien. I read The Hobbit until it fell apart as a child, and have always strived, in my own contributions to the genre, to take even a shred of the care in my world-building that Tolkien did in his. “It is written in my life-blood,” he said of The Lord of the Rings, “such as that is, thick or thin; and I can no other.” A rallying cry for anyone who has known what it is to inhabit a world of one’s own.

“Tolkien was a genius with a unique approach to literature,” says Richard Ovenden, Bodley’s Librarian at the University of Oxford. “His imagined world was created through a combination of his deep scholarship, his rich imagination and powerful creative talent, and informed by his own lived experiences. We are incredibly proud to hold the Tolkien archive and to be able to share so many previously unseen items in this once-in-a-generation exhibition.”

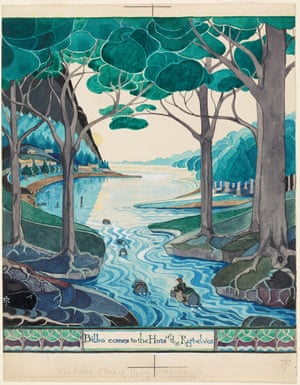

An exhibition, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth, is at the Weston Library in Oxford until October. Visiting before it opens, with preparations still ongoing, I must rely a little on my imagination to colour between the lines. We pass the skeleton of what will be the main entrance to the exhibition; I am told by its curator, Catherine McIlwaine, that the Doors of Durin will be projected into this dark passageway to welcome visitors.

At the heart of the gallery is a model that will chart the routes taken by Tolkien’s characters through the landscape of Middle-earth. As McIlwaine talks me through the items, I find that seeing the exhibition in this liminal state lends an unexpected resonance to the experience. After all, never is a story more alive than when it is in progress.

Though many authors have since found great success in his genre, Tolkien, born in 1892, is unrivalled in his reputation as a meticulous creator who knew his world down to the last blade of grass. Today, Tolkien might have come to represent the old guard of fantasy – the “locker room” that the late Ursula K LeGuin once derided. Yet fierce passion for his work endures, and even his harshest critics will concede that few creators have succeeded in building a paracosm that touches the depth of Middle-earth. Every so often, a new offering will stoke the coals of Tolkienmania – Beren and Lúthien was published in 2017, and this August The Fall of Gondolin will expand on another story from The Silmarillion. Meanwhile Amazon has signed a deal for an ambitious TV adaptation of The Lord of the Rings.

Throughout my career as a writer, I have found Tolkien to be a source of both self-doubt and inspiration. On the one hand, it can be tempting to give up in the face of his brilliance. He began to invent his first Elvish language when he was a student at Oxford, and eventually built a “Tree of Tongues” – one of the items on display in the exhibition – that charted his constructed languages from source. McIlwaine tells me about a painting Tolkien did when he should have been studying for his finals, of the realm of Valinor. “In 1915, it was all there, already in his head,” she explains. Dwelling on this too deeply could induce an existential crisis. More often, however, the knowledge of how fully Tolkien inhabited his work is a catalyst and a beacon. It fuels me to build larger, to dream weirder and to push harder at the bounds of my imagination.

Exhibitions of the Bodleian’s extensive Tolkien collection are rare. Kept in a strongroom with four papyrus scrolls from Herculaneum, the material is tested before and after display and shown in the same womb-like darkness that wraps the Book of Kells in Dublin. Given the importance of preserving the collection, there has been no major exhibition for 26 years. After finishing its run in October, it will travel to New York, then to the Bibliothèque nationale de France. This is the first time the latter will host an exhibition about a foreign author.

It is all too easy to believe in the myth of the professor as the one true god of a world he knew in its entirety. The truth, however, is more complex. Tolkien was not always sure of himself. A notebook page reveals that Gandalf once had the Elvish name Bladorthin, meaning grey wanderer. Gandalf, it turns out, was the original name of Thorin Oakenshield. Tolkien flickers between names in the text, as if torn. “He spoke about sub-creation,” McIlwaine says, “and I think this tied into his religious beliefs that all talents and gifts come from God. God is the one creator, and what we do is in imitation of that. Tolkien was a very humble man.”

There is abundant evidence of his humility. He was uncertain of his skill as an artist, responsive to criticism, and went out of his way to seek feedback from his friends and children. He could also make the most absent-minded of mistakes – for instance, when he forgot to write his own name on the manuscript title page of The Hobbit.

More than 200 items will be on show at the Weston Library, many for the first time – including personal objects donated by the Tolkien family, such as a pipe and a briefcase. Among my favourites is a letter from a fan who has attempted to write a poem in Elvish, which Tolkien has translated and annotated. He was confident enough in his grasp of his world to know when its rules were broken. Rules, after all, are vital in the creation of what he called “secondary belief” in an invented setting – yet he would have been the first to admit that there were uncharted places in Middle-earth.

“I don’t desire to go and have afternoons talking Elvish to chaps,” he once said. “Elvish is too complicated. I’ve never finished making it.”

Although Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth will be free to attend, this is the first exhibition at the Bodleian to be ticketed. “I think people are going to be surprised,” McIlwaine tells me. “We don’t know what they will bring with them, but I’d like them to leave with the impression of the whole man and his work – not just Tolkien as the maker of Middle-earth, but as a scholar, a young professor, a father of four children.”

In this, I believe McIlwaine has succeeded. I am comforted to have glimpsed the man behind the myth, and I am more inspired than ever by the scope of his creation.

The final item I admire is a gathering of patterns in black ink, on the back of a meeting agenda. Its title, written in Quenya, is Parma Mittarion, or “book of enterings”. It was probably intended to be a book cover, but what the book was to contain remains a mystery. Long after I leave the exhibition, my imagination runs wild. I ask myself what Tolkien intended for this book, whether he ever wrote it – either in his mind or on lost pages – and what he could have meant by the phrase “light in the eye”, which he tucked among the decoration. I realise I am beginning to write a story between the lines, and that anyone who looks at the page will perhaps do the same. In this way, Middle-earth will live for ever.

• Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is at the Weston Library, Oxford, until 28 October. tolkien.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is published by the Bodleian Library. To order a copy for £34 (RRP (£40), go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.