Last updated 13:33, May 28 2018

Mycoplasma bovis is the most severe economic biosecurity issue to hit New Zealand, predicted to cost $1 billion over 10 years.

Mycoplasma bovis is the most severe economic biosecurity issue to hit New Zealand, predicted to cost $1 billion over 10 years.

Speculation has been rife over Mycoplasma bovis as the disease has increasingly taken hold on farms.

Q: Is it the worst biosecurity incursion in New Zealand history?

A: Setting aside the disastrous ecological impact suffered by native species since human arrival, Mycoplasma is the worst economic pest or disease to land in New Zealand. The cost of either eradication or management is estimated the same, about $1 billion over 10 years.

The Psa bacteria which hit the kiwifruit industry in 2010 is the next most serious incursion. For that the Government handed out an aid package of $50 million, and a group of 212 growers and post-harvest operators are claiming losses of $376.4m in a case awaiting a decision in the High Court.

Agriculture and Biosecurity Minister Damien O'Connor speaks with Southland Rural Support Trust chairman John Kennedy. O'Connor has described M bovis as worse for farmers to manage than foot and mouth disease.

In 2015 the Ministry for Primary Industries spent $15.7m on an eradication programme after 14 Queensland fruit flies were discovered in Auckland, while in 1997 the aerial spraying operation over Auckland to get rid of white spotted tussock moth cost $12m. The clover root weevil control programme cost $8.2m, while the southern saltmarsh mosquito was successfully wiped out in Hawke's Bay in 1999, at a cost of $6.4m.

Q: How did Mycoplasma arrive in the country?

A: As yet no-one knows, or is telling. MPI is looking at seven pathways: imported live cattle, frozen semen, embryos, veterinary medicines and biological products, feed, used farm equipment, and other imported live animals.

Q: What steps has MPI taken to uncover where it came from?

A: In March MPI staff carried out raids on three locations: Waiheke Island, Tauranga and the Zeestraten farm in Southland. No charges have yet been laid.

The disease has now been traced to the Southland farm of Alfons Zeestraten, at least back to December 2015. MPI says it could have arrived elsewhere even earlier.

Q: Why have the police become involved?

A: The Biosecurity Act requires that MPI staff are accompanied by a police officer when search warrants are executed. The police officer takes no part in the search itself, and police are not involved in the investigation which is being run by MPI.

Q: Has MPI dithered in its response?

A: Agriculture Minister Damien O'Connor has acknowledged MPI is "stretched". On July 21 last year MPI was informed Mycoplasma had been detected on a farm owned by South Canterbury's Aad and Wilma van Leeuwen. Staff arrived the next day to start work on the response. About 250 staff have been involved, more than 60 meetings have been held with 15,000 farmers attending.

Q: Has MPI been fair over compensation claims?

A: Untangling genuine claims from dishonest ones has tested MPI. One farmer included the cost of his family holiday to Australia's Gold Coast in his claim Officials predicted early this year the likely payout could be $60m, but the numbers of infected farms has risen.

Farmers listen intently to an MPI presentation.

Q: Were the Van Leeuwens threatened with jail by MPI?

A: No. When they were informed MPI would like to carry out further testing, the van Leeuwens refused. They were informed if they didn't abide by regulations, they would be open to prosecution. The van Leeuwens asked their lawyers what that meant, and they were told it could mean a fine or they could go to jail.

Q: Will my milk cost more because all these cows being culled will mean lower milk production?

A: No. So far 22,300 cows are being or have been killed. Massey University animal health associate professor Richard Laven estimates that perhaps a total of 240 dairy farms will turn out to be infected. That might mean between 60-100,000 further cows being sent to the freezing works.

There are about 4.5 million milking cows. Even at the top end of a 100,000 cull, that is just over 2 per cent. Last season because of climatic conditions, New Zealand experienced a 2 per cent loss in milk production. Every year more than 1 million cows are culled as farmers replace them.

Q: Did Damien O'Connor describe M bovis as worse than foot and mouth?

A: He said it was more difficult for farmers to manage M bovis because it takes multiple tests spread over months to detect. However the meat and milk from affected animals is safe for humans.

Foot and mouth would be more serious for the economy because countries would stop buying our products. Several years ago Treasury estimated export losses of $14.4 billion, spending of $1.17b on eradication and livestock compensation for infected properties of $30.8m.

In 2001 foot and mouth hit Britain. More than 10 million sheep and cattle were killed and the crisis is estimated to have cost $15.8bn.

Q: Will Mycoplasma mean the end of sharemilking?

A. Talk of the demise of sharemilking - a traditional avenue for farmers to buy their own farms - is alarmist. There's been a steady decline in sharemilker numbers over the past 20 years, from 5016 to 3879. That's because during high payout years farm owners prefer to take a greater share of profits; more corporate farms want to own their own herds; and owners simply can't afford to employ sharemilkers when debt levels are high.

Q: Is the disease a problem only for dairy farmers?

A: Sheep and beef farmers have done well out of the dairy industry, running dairy grazers and using them to improve pasture quality for their sheep. Beef bulls have been mated with dairy cows to produce animals primarily destined for the burgeoning US burger industry. With less animal movement between farms, sheep and beef farmers stand to lose these extra income streams.

Q: How many countries have tried to eradicate M bovis?

A: None. Among major OECD dairying countries, only Norway does not have it. In the United Kingdom, it is now being identified in more dairy herds. A farmer who has had to slaughter all his cows recently said it was a major threat, "but its insidious nature is masking how many herds have it and its rate of spread".

Q: What have farmers done wrong?

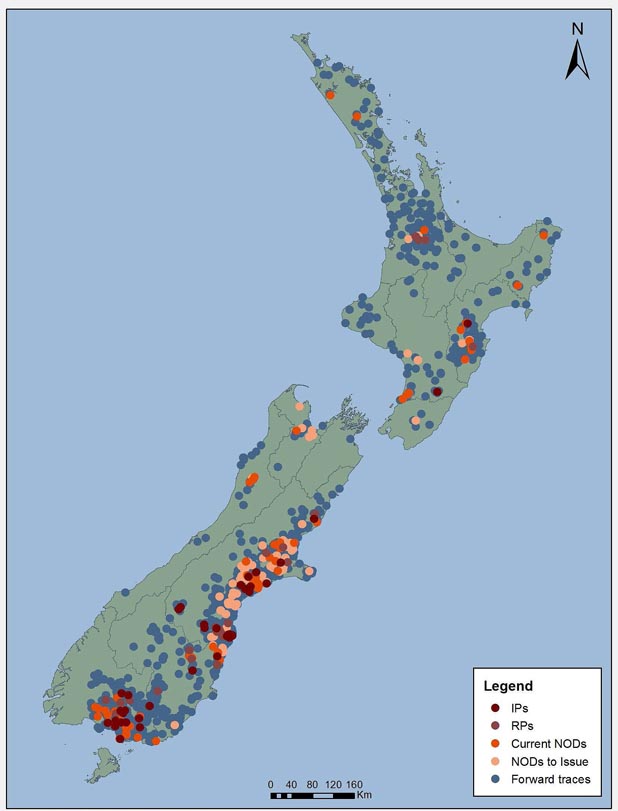

A: Many have not complied with a system introduced in 2012 called National Animal Identification Tracing (Nait). When cattle or deer are born, they are meant to be tagged and registered and their movements around the country have to be recorded. That is what has made it so tough for MPI to track stock.

But MPI has also been guilty of being too soft on non-compliant farmers. In the six years since Nait was introduced, only one infringement fine of $150 has been handed out. The maximum fine is $10,000.

Q: How about the "cash for calves" business?

A: Some farmers have not registered calves and then sold them off for cash. This has not only made it more difficult for MPI to track the calves; it's also attracted the attention of the taxman.

Q: Has anyone been infected with M bovis?

A: The NZ Ministry of Health, which has carried out a review of the subject, says worldwide there have been two reports of M bovis reported in humans. In the first, a woman developed bronchopneumonia after heavy exposure to cow manure, and M bovis was isolated in her throat. The Ministry says details for the second case are "extremely scant." Both patients responded positively to the antibiotic tetracycline.