A cut above the rest: 50 years of Rolf’s Pork Store

A cut above the rest: 50 years of Rolf’s Pork Store

Albany

Clad in a white apron and thick-soled shoes, Edgar Eggelhoefer hunches over a cutting board deftly chopping hunks of meat into manageable pieces for hot dogs and sausages, the same way he has done it at Rolf's Pork Store for the past 50 years.

He cuts off the fat before tossing the meat into a grinder and a cutting machine, a circular metal trench that will turn the chunks into a smooth mixture resembling a thick batter. Spices and seasoning are sprinkled in. The machine has been at it longer than Eggelhoefer, and there are no plans to replace it.

"They make the newer stuff to break," he said.

Rolf’s Pork Store in Albany is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. (Madison Iszler/Times Union)

Media: Times UnionThe soupy concoction is then plopped into a large metal bowl and transferred to another machine, which spits out a steady stream that another employee twists into six-inch links. Then the wieners are off to sweat it out in the smoker for hours before being moved to the cooker and submerged in 160-degree Fahrenheit water. They cool off in a container of cold water before leaving to be packaged and sold for Memorial Day picnics and parties.

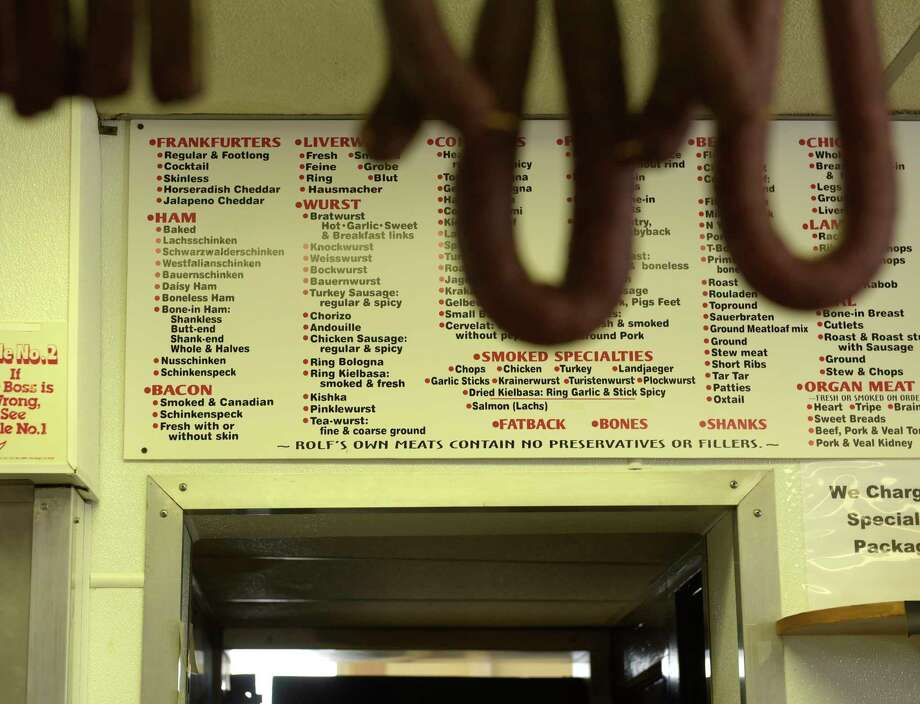

This process will be repeated over and over again throughout the day, using different smoking measures and ingredients depending on the variety of wurst, sausage or hot dog. There are machines to wash down, hundreds of pounds of bacon and ham in different stages of curing to tend to and cold cuts to set out — the store makes more than 60 products in-house.

By the time they hang up their aprons, Eggelhoefer and his team will have made between 2,000 and 3,000 hot dogs. During the week leading up to Memorial Day, they'll sell 700 pounds of hot dogs, 400 pounds of sausages and 800 hamburger patties.

"We're some of the last ones left doing this," Eggelhoefer said.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Rolf's Pork Store, a meat market on Lexington Avenue that Edgar and his brother Glen's father Rolf bought in 1968. But the shop has a far longer history: two other families owned and operated it on the same block under different names for a combined 100 years. At 150, it's the oldest existing meat market in upstate New York, the brothers aver.

For many customers, Rolf's offers a taste of home and a glimpse of a bygone era — a place they can find tangy German potato salad, wurst of every variety and a type of ham, native to the Black Forest region, called Schwarzwälder Schinken. The shelves are lined with spaetzle and German chocolate and the magazines and newspapers are German. Red, yellow and black T-shirts and flags hang from the ceiling, and customers can talk to the butcher face-to-face about the cut they want.

"There's nothing we can't do when it comes to the meat world," said Glen. "We're in the 1 percentile."

The brothers learned everything they know from watching and working alongside their father, who sold them the store in 1987. Rolf was trained as a professional meat-cutting meister in Germany and he and his wife, Waltraud, moved to the United States in 1958. They landed first in New York City, where Rolf worked at Forest Pork Store in Queens for a decade, and then moved to Albany where he bought the market that would become Rolf's.

When they arrived in the Capital Region, Lexington Avenue was a busy thoroughfare lined with restaurants, bars, hair salons, a bakery, a barber shop, groceries and other businesses. There were two other meat markets around the corner from Rolf's. The surrounding neighborhoods were predominantly German and Polish and foot traffic dominated Rolf's business. Many worked at the railyards and others fixing cars and machines or working in various blue-collar trades.

"The men were machinist(s), mechanics, brakemen, firemen, switchmen and engineers, carpenter, electricians and plumbers," the Rev. Joyce Hartwell wrote in a history of Albany's West Hill and West End. It's unclear when the history was written.

But the rise of automobiles and refrigerated railroad cars hit the industries hard, Hartwell explained, and the railroad and livestock areas were auctioned off. People then launched their own small businesses, "often operating out of the surrounding homes" in the area.

The neighborhoods "suffer from a lack of employment, aging housing stock, and aging population," Hartwell added. Many buildings have fallen into disrepair, and investment from landlords and business owners has been limited. The area also suffers from some of the worst crime rates in the city. A 2017 report by the Times Union called West Hill the "epicenter" of gun violence, noting that 46 percent of reported shootings in 2016 occurred in the neighborhood though only 10 percent of Albany's population lives there.

Many buildings have fallen into disrepair. City planners outlined seven focus areas in a 2015 report on the neighborhoods, including housing, business and workforce development and transportation, and organizations like Habitat for Humanity Capital District are trying to revitalize the area with plans to build new residential and commercial buildings.

Rolf's customer base has changed along with the neighborhood. Their typical client drives an average of 20 miles to get there, Glen Eggelhoefer said. He used to get as many as 250 customers on a Saturday; now he's lucky if 130 come in.

The food industry and people's habits have also shifted. In the past people did their shopping at small neighborhood stores where they often knew the owners and employees and bought items from specialty shops, like getting their bread from a baker. Now many buy their groceries at large supermarkets like Price Chopper and Hannaford because it's quicker, more convenient and sometimes cheaper.

Years ago it was more common for women to stay home and do the bulk of the shopping and cooking, while nowadays more couples share the responsibilities and there are more women in the workforce, Glen Eggelhoefer said. Even the times people buy their food have changed: people used to be waiting outside Rolf's door early in the morning, while now they do most of their shopping in the afternoon or evening.

"Everyone is in a hurry," he said.

People don't buy the same variety of cuts they used to, and butchers and meat cutters don't cut the same way. They used to string up an entire animal and break it down piece by piece, Glen said.

There are also fewer independent butchers and meat markets, especially those that sell prime beef, and people source their meat differently. Troy Pork Store closed in 2008 after 90 years in business, and Falvo's Meat Shoppe on Route 85A in Slingerlands was put up for sale in April. The future of the Latham Meat Market is unclear after owner Peter Kounoupis died earlier this month. Glen says the survival or closure of such markets can depend on whether knowledgeable relatives are able or willing to take over the business.

"You have to know what you're doing in this business to make it work," he said.

Others have expanded the items and products they carry or added features catering to convenience. The local chain of Primal butcher shops recently partnered with Mindful Meals To Go to stock prepared meals in-store.

After his butcher shut down in 2008, Greg Stratton learned how to cut his own meat and opened Stratton's Custom Meats & Smokehouse in Hoosick Falls. He butchers meat on-site for customers in Vermont, Massachusetts and upstate New York and doesn't do any retail sales.

"A lot of people appreciate and love that we go to them," Stratton told the Times Union in 2016. "Mainly because they don't have a way to transport their animals to another shop and because the animals aren't under stress because they aren't in a strange place."

Consumers' growing interest in eating organic, minimally processed foods and knowing how their food is made has boosted stores and businesses that emphasize direct-to-consumer sales. People can buy their meat directly from farmers through farm share programs, farmers' markets or retail stores at farms.

It's helped draw new customers to places like Rolf's, Glen Eggelhoefer said. Their products don't contain any artificial flavors, preservatives, tenderizers or cereal — they recommend customers eat their meats within five days of buying. Some of their customers are people with food allergies and other health issues who can't eat foods made with gluten or other substances.

"People are starting to be more aware of what they eat," he said.

He credits customers' loyalty to the store's emphasis on all-natural.

"You take a store that's in a not-so-good neighborhood, yet I have a lot of customers," Glen Eggelhoefer said. "People that come here go out of their way, they have to drive a bit, and it's because they care about what they eat and we are one of a kind."

The brothers have considered moving the store many times. But they are proud of the store's history in the community, and it's cheaper and easier to to stay put. Edgar may retire in the next few years, but Glen's not there yet.

"They're going to have to roll me out," he said.

miszler@timesunion.com • 518-454-5018 • @madisoniszler