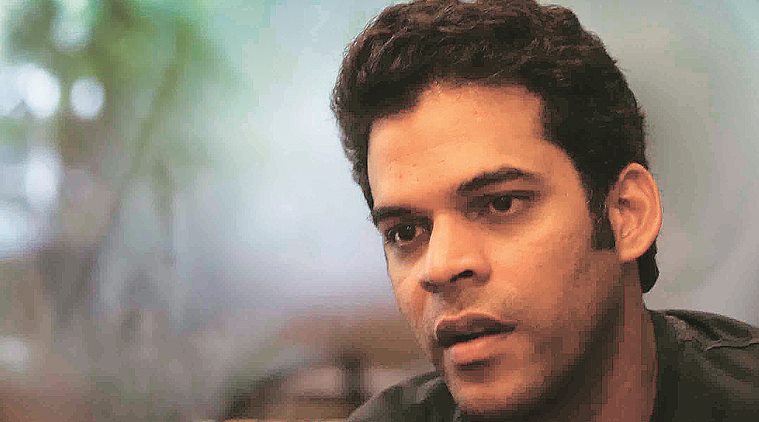

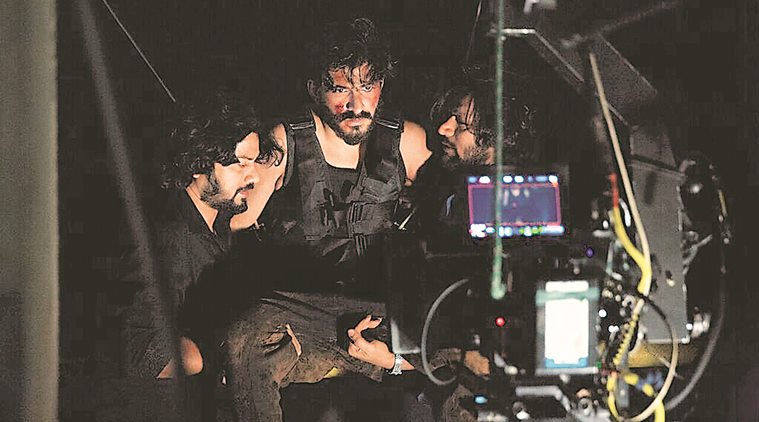

Vikramaditya Motwane; a still from Bhavesh Joshi Superhero

Vikramaditya Motwane; a still from Bhavesh Joshi Superhero

How long have you been interested in graphic novels and comic books?

My whole life, really. It started with Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha. Growing up, Tinkle was a part of my life, of an entire generation, actually. The way we waited for a new issue every fortnight. And I think the only version of Ramayana I’ve ever read is the Amar Chitra Katha version (laughs). They were also quite graphic, you know, with Krishna lopping off heads with his Sudarshan chakra.

You have a lot of Batman comics and posters in your office. Have you always been interested in vigilante characters and their idea of justice?

If we go back to the birth of Superman and Batman in America in the ’30s, they were created because of events like the Great Depression, crime and Al Capone, among others. Everybody was corrupt back then, and if you can’t have a hero in real life, it helps to have one in your fantasies. Then you can look at the ’70s in India with the Salim-Javed films and their Angry Young Man — because somebody needed to go out there and do something. I think vigilantism is a pipe dream, because the larger need is for a justice system that works. Now, Batman cannot be Batman without police commissioner Jim Gordon, because every time he catches a villain, he tries to send them to Gordon. So, the idea is to help the justice system to work. I don’t think it can work in real life, though.

But, in your film, Bhavesh Joshi Superhero, you’re getting a chance to look at justice, personal agency, the idea of being a citizen. So that must mean something to you.

Of course. The birth of this film can be traced back to some years ago when I was driving around Mumbai and looking at what this city has become. I began writing this in 2011, when Anna Hazare was leading a movement against corruption.

Bhavesh Joshi Superhero also tackles corruption. But the script saw some changes in the subject matter, didn’t it?

Yes, the initial story was about land grabbing and developers. It was about a guy who has a neighbour who cared about a playground that was going to be taken over by a bunch of politicians and contractors.

“The birth of this film can be traced back to when I was driving around Mumbai and looking at what this city has become. I began writing this in 2011, when Anna Hazare was leading a movement against corruption,” says Vikramaditya Motwane

“The birth of this film can be traced back to when I was driving around Mumbai and looking at what this city has become. I began writing this in 2011, when Anna Hazare was leading a movement against corruption,” says Vikramaditya Motwane

Something like Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru?

Yes, but what happened was that the idea, which seemed so important in 2011-12, had lost its relevance as the years progressed. I felt like nobody was talking about this anymore. When I rewrote the film, I felt that water really is what we need to worry about now. It started off as a futuristic problem but look at how things stand — Cape Town’s run out of water, Bangalore is running short, and in Mumbai, if we have one bad monsoon and our lakes go dry, we’re screwed. The borewells are illegally tapped into, and it’s already a political agenda. I remember seeing a local MLA’s poster saying that he is promising 24 hours water supply. We pay taxes for that, how dare he think this is not our right. At one level, I want to talk about rights and corruption but a large part of it is also connected to a childhood fantasy of making a really cool action film with bike chases and masks (laughs).

In a previous interview, you mentioned Mr. India (1987) as one of the influences. Bhavesh Joshi, played by Harshvardhan Kapoor, also has red eyewear, just like his father did as Mr India. Was that deliberate?

Not at all. Harshvardhan came to the project much later, the costume details had already been decided. There’s a story behind the red LED lights, he’s got no money, he makes his own gear — he’s a cottage-industry superhero.

The film fell through twice. Why?

The first time I’d cast Imran Khan and I couldn’t get funding for the film. Then things with Sidharth Malhotra didn’t work out. It had been six months since a new government came to power in the centre in May 2014, and the idea had begun to feel dated. My entire approach to the script changed

after that. Harshvardhan wanted to work with me for some time. He auditioned for the role in 2012 and I rejected him then because I

felt he was too raw. Once I changed the script, he auditioned again. This time, it worked because I’d changed the character: somebody sincere, less cynical, trying to find his own feet.

Is this going to be a sequel or standalone film?

So far, standalone. If it does phenomenally well, and it makes some money, I’ll go for a sequel.

Udaan was set in Jamshedpur, Lootera in Bengal. But all your recent projects — Trapped, Bhavesh Joshi Superhero and Sacred Games for Netflix — are located in Mumbai. Why is this impossible city your muse?

I’ve never lived anywhere else in my life, I have a massive love-hate relationship with this city. I grew up in the western suburbs in the ’80s and for everything we had to go to south Bombay — so you lived the whole city, in a sense. But when the name change happened, Bombay turning to Mumbai, I felt like this city doesn’t belong to us anymore, it belongs to political parties. There’s still so much to love, it’s such a diverse and democratic city.