H D Deve Gowda (left) and H D Kumaraswamy.

H D Deve Gowda (left) and H D Kumaraswamy.

When he was chief minister of Karnataka in 1994, a statistic provided by the then police chief had caught H D Devegowda’s attention: less than 0.1 per cent of constables in the state’s police force were Muslims. “Are they not people of this country, I wondered,” Devegowda, 85, said recently on television while talking about how he was the first in the country to accord four per cent reservation in government jobs to Muslims.

The quota saw a large number of Muslims entering government services — their representation in the police department, for instance, stood at 7 per cent till a couple of years ago — and ensured that the community, which makes up nearly 10 per cent of the state’s population, considered the JD(S) as an alternative to the Congress.

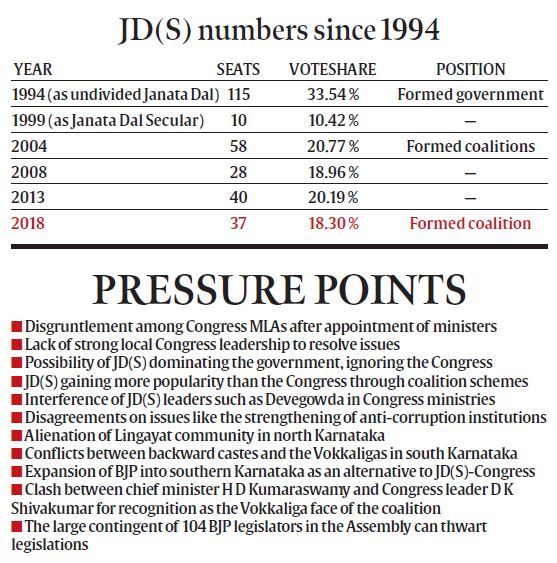

Often criticised and laughed away for practising a family-centric brand of politics, it’s this old-school socialism that has been the JD(S)’s strength even as it wallowed in near-obscurity after the high of 1994, when the party won 115 seats and Devegowda became chief minister. The best performance since then has been the 58 seats the party won in 2004 and Kumaraswamy became chief minister for the first time. But now, a hung verdict in the May 12 Assembly elections in Karnataka has given the JD(S) an unexpected chance to arrest a gradual spiral into irrelevance and an opportunity to rebuild for itself a pan-Karnataka base instead of being restricted largely to southern Karnataka and the Vokkaliga community, which has considered Devegowda its patriarch for several decades now.

In a quirk of fate, despite winning only 38 seats in the 224-member Karnataka Assembly, Kumaraswamy, 58, Gowda’s third son, became chief minister of Karnataka after the Congress offered its 78 MLAs in an act of unconditional support to keep the BJP, the single largest party with 104 seats, out of power.

“One of our main aims in tying up with the Congress is to build the image of the JD(S) again in the state. We have been out of power for 12 years and we want to increase our base again by providing a stable, secure government. The Muslims have all drifted away from us and we need to re-emerge as an alternative to the Congress,” says a JD(S) leader.

It’s an admission of the failed alliance between the BJP and JD(S) in 2006, after Kumaraswamy walked out of the Congress-JD(S) coalition government, much against the wishes of his more secular-minded father. That alliance with the BJP also meant that one of the JD(S)’s strongest votebanks, the minorities, grew suspicious of it and stuck with the Congress.

In the 2008 election, its voteshare fell to 19 per cent from the 21 per cent of 2004, when the party won its all-time high of 58 seats since emerging as a separate party from the kernel of the Janata Dal that ruled the state in 1994. While the party has retained a base of around 19 per cent votes in the Vokkaliga-populated south Karnataka districts of Mandya, Hassan, Ramanagaram, Kolar and rural Bengaluru, it has lost ground in the north. In 2013, its voteshare increased to 20 per cent but dipped again to 18 per cent this year as Muslim voters rallied behind the Congress. Another key reason why the JD(S) favoured an alliance with the Congress over a tie-up with the BJP was the greater flexibility it would have. “The BJP is a more rigid party. It also has a larger number of MLAs than the Congress and poses the danger of engulfing our MLAs at some point in time,” says the JD(S) leader.

***

Devegowda (extreme right) with Lalu Prasad (centre) and Jayalalithaa in an undated photo.

Devegowda (extreme right) with Lalu Prasad (centre) and Jayalalithaa in an undated photo.

Through all its years of near obscurity in state and national politics, the JD(S) has remained a formidable force in the South Karnataka region. To the largely agricultural Vokkaliga or Gowda community, who make up nearly 15 per cent of the population in southern Karnataka, both Devegowda and Kumaraswamy are virtual folk heroes.

For instance, last week, as it became clear that Kumaraswamy was going to be the chief minister, among those who lined up to meet the father-son duo was a frail, 66-year-old, barefoot farmer from Devegowda’s hometown, Holenarasipura. The farmer, Gopal Gowda, had taken a vow before the elections that he wouldn’t wear any footwear until Kumaraswamy became CM and waived off farm loans.

Last week, he arrived barefoot at Devegowda’s home and prostrated at the feet of the former prime minister to tell him that his penance for Kumaraswamy had paid off.

“My father-in-law was a friend of Devegowda’s. When he died in a hospital in Bengaluru in the 1990s, Kumaraswamy, who had not entered politics then, took my father-in-law’s body from hospital and brought it to our village. I am indebted to him for that gesture,” says the 66-year-old.

During the May 12 elections, the charm and popularity of the Gowdas were most evident in two constituencies — Magadi and Nagamangala — in southern Karnataka. With the Congress poaching its two stalwarts MLAs H C Balakrishna and N Cheluvarayaswamy, from these two seats, the JD(S) fielded relative novices — A Manju and Suresh Gowda — both of whom won their seats with margins in excess of 40,000 votes.

“The image of my leaders helped me win. I would say that the high regard for Devegowda and Kumaraswamy in Magadi contributed 100 per cent to my win,” says Manju.

While the politics of father and son is largely known to be pro-farmer and pro-rural, many say their contributions to urban growth and employment is often ignored.

It was Devegowda’s brief 18-month tenure as chief minister, between 1994-95, before he became prime minister, which opened the doors for the advent of the IT industry in Bengaluru through changes in land-usage rules. The JD(S) leader also paved the way for the opening of the first major IT park in Bengaluru — the Singapore International Technology Park Limited — in the late 1990s.

In his first tenure as chief minister in 2007, Kumaraswamy created the greater Bangalore region by expanding the spread of the city from 226 sq km to 800 sq km, bringing over two million people living on the periphery of the city within the city’s limits.

“My aim then was to make use of the nearly Rs 25,000 crore funds available to cities under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission of the UPA to fuel the growth of Bengaluru. This did not happen after we lost power,” Kumaraswamy said recently.

Bureaucrats who worked with them also speak fondly of the Gowdas. “They care for figures and data. They look at resources and tailor programmes accordingly,” says former IAS officer S Subramanya about the father-son’s approach to governance. Subramanya had worked with the duo for over a decade, crafting policies and an economic agenda for the JD(S)’s politics in Karnataka.

S Y Hadimani, former head of the Organised Crime Wing of the Central Crime Branch of the Bengaluru Police, says Kumaraswamy never patronised anti-social elements. “Many politicians support anti-social elements and allow them to thrive. This is not the case with Kumaraswamy. He allows officers to do their jobs without interference,” he says.

Kumaraswamy, who has his own TV channel, Kasthuri, is known to have an easy relationship with the media. His alliance partner, the Congress, is said to have advised him to foster the media to combat the “negativity towards the coalition” on social media.

“I will consider those who criticise me as my friends. Only when you listen to those who criticise you more than those who praise you, can you hope to stay on the right track,” Kumaraswamy said after he became chief minister of Karnataka.

In the past, however, coalitions forged with the JD(S) — by the Congress in 2004 and the BJP in 2006 — have been plagued by allegations of constant interference from Devegowda. “Devegowda would constantly send missives on government issues and this used to cause a lot of tension,” former BJP chief minister B S Yeddyurappa told the state legislative Assembly on May 25 during the floor test that the JD(S)-Congress government won.

A Congress leader who had a ringside view of the Congress-JD(S) coalition headed by Dharam Singh between 2005-2006 says, “Dharam Singh had to constantly answer questions from Devegowda who was like a super CM. The situation now is very different since Devegowda’s son Kumaraswamy is the Chief Minister and we do not expect similar interference. Kumaraswamy will also be able to tolerate interference better.’’

After a meeting with his father the morning after taking oath, Kumaraswamy said, “We discussed the political situation in the state and he advised me about the policies to be adopted for securing the government.” Devegowda too has stated since the formation of the coalition that he will guide the new government using his “experience and knowledge of governance”.

***

One of the factors weighing on the minds of most people in Karnataka as the JD(S)-Congress coalition takes office in the state under Kumaraswamy is whether the arrangement is a stop-gap measure that will last only until the 2019 parliament polls.

Kumaraswamy and other JD(S) leaders have, however, been at pains to dismiss such scepticism. “The only person who is focussed on national politics in the JD(S) at present is Mr Devegowda. Everybody else is interested in local affairs and want the alliance to last for five years,” says an advocate associated with the JD(S), referring to the Sr Gowda’s larger role in the event of the Opposition parties rallying together against the BJP ahead of the 2019 elections.

“From the responsibility given to me in the present political situation, I tend to think I am a child of circumstances. There is a strange situation that has arisen in Karnataka at present. There are doubts about this coalition among a lot of people and I want to tell them that we will try to change their impression with our work in the coming days,” Kumaraswamy told reporters after taking oath as CM. Kumaraswamy has also claimed to have greater resolve and patience to run a coalition now than he did in 2007, when he walked out of an alliance with the BJP.

“We are determined to make this coalition with the Congress work. If we do not make it work, then people will lose all faith in coalition governments in the state. I am not trying to praise him but Kumaraswamy is a person who takes mature decisions. He is very judicious and this will help us run the government,” says JD(S) leader and former minister Basavaraj Horatti.

The Opposition BJP in Karnataka has, however, warned the Congress that it should be prepared to cede all administrative control in the state to the JD(S). “Kumaraswamy says he is a child of circumstances. What he means is that he is a political opportunist who will change his colours as the situation demands,” said Leader of the Opposition and former BJP chief minister B S Yeddyurappa during the trust vote on May 25. “They will slowly finish the Congress and only the JD(S) will remain,” he warned.

On the ground, especially south Karnataka, where the JD(S) cadre battled the Congress bitterly in the elections, it’s unlikely to be smooth sailing for the coalition.

In these Vokkaliga-dominated districts, one of the biggest reasons for anger against the Congress is the systematic sidelining of the community from important positions in government departments and the promotion of backward castes during the tenure of the Congress government headed by the backward caste leader Siddaramaiah. Now with the JD(S) joining hands with the party, it will have to find a way to assuage the apprehensions of voters here.

“The coalition will have some tension only in south Karnataka. The onus of protecting the interests of backward castes like the Kurubas, the Dalits and even bigger communities like the Lingayats spread across the state still vests with the Congress,’’ says a senior Delhi-based leader of the Congress.

For the JD(S), there are challenges on the personal front too. Kumaraswamy’s decision to contest from two constituencies — Ramanagaram and Channapatna in the Vokkaliga heartland — is widely reported to be the consequence of a feud for more political prominence among members of his own family. Kumaraswamy, who won from both seats, has decided to retain Channapatna.

Kumaraswamy originally intended to field his wife Anitha from Ramanagaram but was forced to drop the plan after his sister-in-law Bhavani Revanna asked that her son Prajwal Revanna be given a ticket as well if Anitha was being fielded.

The family rancour came to the fore when some television channels aired footage of Bhavani canvassing against the JD(S). In the end, Devegowda had to settle the dispute by declaring that only two persons from the family — Kumaraswamy and his older brother Revanna — could contest the polls. “Prajwal will build the party and attract youths to the party,” Prajwal himself announced after the polls.

***

Kumaraswamy (extreme right) with Rahul Gandhi and other opposition leaders after the swearing-in ceremony in Bengaluru on May 23

Kumaraswamy (extreme right) with Rahul Gandhi and other opposition leaders after the swearing-in ceremony in Bengaluru on May 23

For now, nothing illustrates the overnight transformation of the JD(S) — from a party on the precipice of political oblivion to one that is now holding the reins of power in Karnataka — better than the scene outside two south Bengaluru neighbourhoods, Padmanabhanagar and JP Nagar, where the homes of Gowda Sr and Jr are located.

These neighbourhoods, around three kilometres apart, where children played badmintion on the streets and joggers gently trundled around in the morning hours, have transformed into hubs of political activity since the May 15 results of the Karnataka Assembly polls. Senior bureaucrats, policemen, politicians and businessmen have all been lining up alongside JD(S) party workers and the media outside the homes to gain access to Devegowda and Kumaraswamy.

Says a reporter from a local Kannada television channel who has covered the JD(S) for several years, “On the morning of the results, there was not a soul around Devegowda’s house. The cleaning woman swept the front yard leisurely. By the afternoon, the media crews began arriving. By the evening, the party workers arrived. Soon the gates and doors which were always open had to be locked up.”