The name of a new exhibition at the New York Historical Society examining Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, and the political context in which they were conceived, is Enduring Ideals. The ideals in question – freedom of speech and worship; freedom from want and fear – were elucidated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, first in an ad-libbed conversation with reporters at his residence in Hyde Park, and later in his 1941 State of the Union address.

Though it’s been gestating for about four years, there is a power, and an obvious irony, to the exhibition being staged in 2018, exactly 75 years after Rockwell’s paintings were reproduced as posters for the Saturday Evening Post. Power, owing to the urgency of Roosevelt’s words and Rockwell’s virtuous interpretation of them; and irony, since on the day the exhibition was previewed to the press, the current president resoundingly approved of a rule curbing the free expression of NFL players while parroting conspiracy theories about the FBI and a supposedly “criminal Deep State”.

That’s not to say Roosevelt’s speech, or Rockwell’s visual response to it, made manifest the four freedoms articulated in January of 1941. Both men, at heart, were sentimentalists who often better reflected how America saw itself than how it actually was. Nevertheless, when perusing the exhibition – on view in New York through the summer before it travels overseas – one gains an appreciation for Roosevelt and Rockwell’s bygone vision of national unity, one that proved galvanizing during wartime if not exactly impregnable.

At the center of the exhibit, the Four Freedoms face one another in an octagon. The first, Freedom of Speech, and the only one based on a true event, depicts a man making his voice heard at a town hall meeting. Freedom of Worship, which ran in the Post a week later, shows several heads bowed in prayer. Freedom from Want, the most familiar of the four, depicts a festive Thanksgiving dinner. And Freedom from Fear features two children being tucked into bed by their parents as the father holds a newspaper with the words “bombings” and “horror” on the front page.

Together the paintings emphasize how Rockwell, in defiance of what his biographer Deborah Solomon described as a “repressed” and “obsessive-compulsive” character, captured the American ethos and its fabled spirit of harmony perhaps better than Roosevelt himself.

“The Four Freedoms actually failed to gain traction among Americans,” said James Kimble, co-curator of the exhibit and a professor at Seton Hall University, at the press preview. “It was such an abstract ideal to them. Now, a number of rhetoricians have named it one of the top 50 speeches of the 20th century, but at the time it was, in a sense, a dud.”

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, deputy director and chief curator of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, adds: “Rockwell, unlike some of the American public, was quite struck by these ideals that Roosevelt articulated … He called them ‘lofty’ ideals, and he wanted to find a way to bring them home to the American public.”

After the paintings appeared in four 1943 issues of the Saturday Evening Post alongside essays by contemporaneous writers and intellectuals such as Carlos Bulosan and Will Durant, the US treasury department did just that, putting Rockwell’s Four Freedoms to use as a form of wartime agitprop on its 16-city war bonds drive, which raised $133m.

The exhibit lends context, too, surrounding Rockwell’s work with several of JC Leyendecker’s illustrated covers for the Post: one, from 1943, shows a baby in a hard hat brandishing a gun. Others, like those distributed by the Office of War Information, are similarly frank. In This is the Enemy, a man with a swastika insignia sticks a knife through a Bible. Another shows Uncle Sam, dressed in red, white and blue, rolling up his sleeves as the words “Jap … You’re Next!” appear above him. In Rockwell’s oil painting Rosie the Riveter, which appears beside J Howard Miller’s famous depiction of Rosie flexing, she eats a sandwich while bludgeoning a copy of Mein Kampf under the sole of her penny loafers.

If Enduring Ideals is primarily a homage to the principles expressed by Roosevelt and Rockwell, it is by proxy a celebration of print media, which limps along more than it endures. “One of the things we have a hard time getting our heads around now is that print was the center of the universe in the mid-20th century,” says Haboush Plunkett. “Magazines were really central in shaping the way people felt about things. So the fact that Rockwell was a popular Post illustrator, and the Post having 4 million subscribers at the time, really galvanized American opinion.”

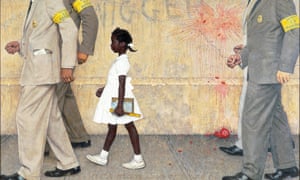

The exhibition, which will travel to Normandy next year on the anniversary of D-Day, is split into sections. One room is dedicated to the war generation and features the photographs of Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein. Another, called Freedom’s Legacy, shows Rockwell’s well-known painting of Ruby Bridges, a black girl attending a white school, as well as Murder in Mississippi, an illustration of the killing of three civil rights activists at the hands of the KKK.

Beyond the gallery, the spirit of Roosevelt and Rockwell persists. Outside the building are freedom-themed sticky notes spread across the New York Historical Society’s glass walls, where visiting students are encouraged to document their own hopes by filling in the blanks: freedom of “access”, reads one, alongside freedom of “expression”, freedom from “environmental degradation”, and freedom from “Trump”.

While the exhibition itself transports viewers to mid-century America, evoking a moment of both crisis and confederacy, it’s the sticky notes outside that remind us ideals are only enduring if we make them so.

- Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms will be on display at the New York Historical Society until 2 September