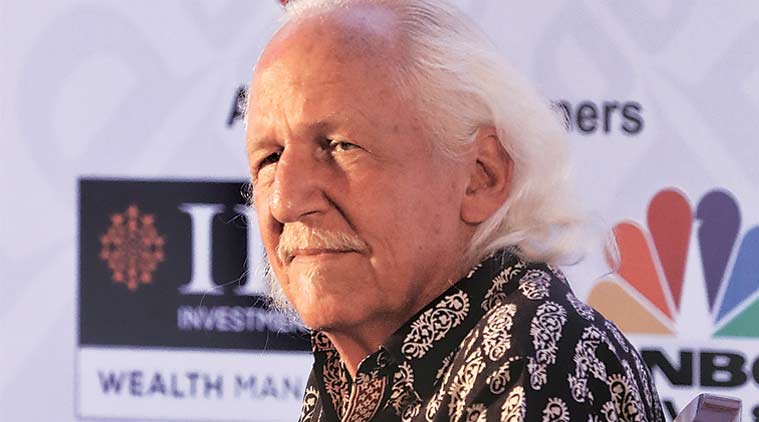

Romulus Whitaker at the Express Adda Thursday. (Photo: Abhinav Saha)

Romulus Whitaker at the Express Adda Thursday. (Photo: Abhinav Saha)

“FIFTY THOUSAND people die of snake bites every year, and many more thousands end up being permanently injured because of them. We are looking at a rather big, a rather drastic problem here. There are several reasons for this, all solvable reasons, since snake bites are accidents, they are avoidable.”

It’s this message that India’s ‘snake man’, wildlife conservationist and self-taught herpetologist Romulus Whitaker wants to “get out there to the people in rural India”. “It’s not an easy job,” he said at the Express Adda Thursday.

It was while studying incidents of snakebites in India that Whitaker discovered that numerous lives were lost due to inadequate production and distribution of anti-venom serum. Over the years, he has been working closely with the Irulas of Tamil Nadu, a tribe of snake-catchers to set up a cooperative, that under licences from the Wildlife Department, supplies snakes, extracts and freeze-dries venom and sells it to anti-venom laboratories.

“The Irulas are the best snake hunters in the world. They see a small track on the ground and they will tell you which species it was. They were hunting them for their skin. When the Wildlife Act came into being in 1974-1975, they ran out of jobs. We hatched this idea together, of a venom cooperative, which we registered in 1978. They now catch about 8,000-10,000 snakes a year, bring them to the Irula cooperative, extract their venom and then release them back into the wild. This is used to make the anti-venom — the only cure for snake bites. They play a very crucial role in saving lives,” said Whitaker, who was awarded the Padma Shri this year.

At the Adda, Whitaker spoke at length about the prejudice and misbeliefs that surround snakes. “We are a country steeped in a lot of misbelief about snakes, things that are almost religious in belief and stuff. It’s a little bit awkward to say that whatever your grandfather told you is a lie. Snakes are not after us, they are actually frightened of us… If we didn’t have snakes we would be overwhelmed by rats for sure — rats, rodents, are in general, the snake’s favourite food,” he said.

Awarded a Padma Shri this year for his outstanding work in nature conservation, Whitaker will be the guest at the Express Adda in Delhi Thursday.

Awarded a Padma Shri this year for his outstanding work in nature conservation, Whitaker will be the guest at the Express Adda in Delhi Thursday.

A naturalised Indian citizen, Whitaker was born in New York and moved with his family to Mumbai in 1951. He grew up with a python as a pet, which was often used as a ruse to discourage uninvited guests by his grandmother, Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay. “We stayed in an apartment in Marine Drive, Mumbai. And one fine day, the snake had disappeared from the box it was kept in. I went about the whole apartment building knocking on doors and asking for my missing pet — a python named Samson, about 8 feet long. We finally found him under a trunk in our store room,” he said.

This is not Whitaker’s only story about missing snakes. On a train ride from Kodaikanal to Mumbai, he was shaken awake by his sister to see his sand boa poking his head out from the bag he was being carried in. “He had crawled through the knots. I sealed the bag shut and then put it another bag. But imagine the consternation. There are many more such stories,” he said.

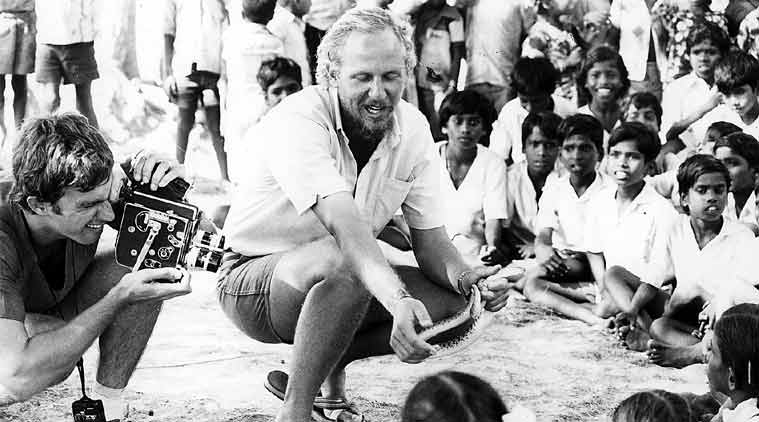

Whitaker, who authored ‘Snakes of India’, has also produced the much acclaimed documentary for National Geographic called ‘The King and I’, which focuses on the King Cobra, the largest venomous snake in the world, and went on to win an Emmy in 1998.

While global warming and shrinking habitat is hitting many species, snakes in India, says Whitaker, are in a good place. “Ever since the snake skin industry was stopped, it was a great fillip for snakes. Since then, a lot of development is anti-snakes and anti-wildlife in general. But I think snakes are doing well. There is an awareness about reptiles and snakes. For me, it’s a very positive trend. There are some species in parts of the Western Ghats, where because of the dam projects coming up and pieces of forests being destroyed, we might have extinction happening. But snakes, by and large, are doing pretty well in India,” said Whitaker.

In response to a question on the state of zoos in India, Whitaker said, “It will be awkward to discuss zoos, as we have one of the larger ones in the country — the Madras Crocodile Bank which we operate — with 2,500 animals. Some zoos are better than the others. What is sad is how we don’t allow children to touch a snake anymore. I understand why this ruling came out in the first place as many people would mishandle snakes and so on. But, it’s used worldwide — when a child is allowed to touch a snake with the supervision of an expert, it opens a whole world of excitement for the kid. I wish that could somehow change. A zoo of course performs a wonderful function for city people, particularly, as they never have an opportunity to see animals up close. If it’s done well, a zoo is a wonderful thing to have.”

Whitaker is credited with having set up the Madras Snake Park in 1972, followed by Madras Crocodile Bank in 1976. The bank, which is based in the outskirts of Chennai, acts as a one-of-its-kind gene bank for crocodilians apart from being a premier space for herpetological research.

At the Express Adda, Whitaker was in conversation with The Indian Express Deputy Editor Seema Chishti and Assistant Editor Sowmiya Ashok.

Past guests at the event include the Dalai Lama, J&K Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, economist and Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, veteran journalist Mark Tully, Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian, writer Amitav Ghosh and cricketer Virat Kohli.