Defeat hit hard and so did the coach, apportioning blame and pointing the finger; they had let everyone down, he said. It was 2001, Spain had been knocked out of the U17 World Cup, and during the flight home Fernando Torres and Andrés Iniesta, close friends since they had met at 14, decided to put their feelings into words. As they sat on the plane, they wrote a letter outlining everything that had gone wrong. They never posted it but the writing helped and when they touched down back at Barajas airport they swapped shirts, dedicating them to each other. On the shirt Fernando handed to Andrés, it read: “One day you and me will win the World Cup together.”

Nine years later, they did. Eight years after that, they bade farewell together. Six hundred kilometres apart but on the same day – the kids, fathers now, who scored the two most important goals in Spain’s history, in Vienna in 2008 and Johannesburg in 2010, played their last games at their clubs. Their paths have not been the same, but their departures shared more than just a date and because there are two of them, friends, team-mates and popular idols, because they leave the country, the loss feels more significant still.

Iniesta’s official send-off was on Friday. Samuel Eto’o and Xavi Hernández were among those there; Real Madrid were represented by Emilio Butragueño, video messages were played, Pep Guardiola and Sergio Ramos appearing; and Iniesta’s shirts sold with the number on its side, infinity instead of eight. On the same night, Torres had begun his goodbye from the statue of Neptune in central Madrid, thousands of fans before him, celebrating their Europa League success against Marseille; 55,000 had gathered there where Torres said he had stood himself 22 years before, back when he was 11.

But while their departures had been announced some time ago, even though they’d had moments that felt like farewells already, Iniesta dancing his last waltz in the Copa del Rey final, Torres lifting the trophy in Lyon, and although they’d been commemorated three days earlier, this time really was the end.

At the Camp Nou, where Xabi Prieto was also bowing out, a huge mosaic read: “Thanks for so much.” Iniesta collected the league trophy at the end of the match. It was the 32nd he has won with Barcelona, the 35th overall. In his farewell letter Torres had said: “Thanks for so much and sorry for [giving] so little.” He won the World Cup with Iniesta, two European Championships as well, but as Atlético celebrated the Europa League success, Torres insisted: “This is the best thing I’ve won, without doubt.” There was a reason for that: he has won only four major club competitions and just one with Atlético – that one.

Torres lifted the trophy, captain Gabi inviting him to join him, just as Antoine Griezmann had invited him to. With a couple of minutes to go, Torres was still on the bench; that was when Griezmann ran across and told Atlético’s assistant manager, Germán Burgos, to send him on. In his penultimate game for the club, he won his first title. As he stood before fans the following night he insisted: “For all those kids who have dreams: nothing is impossible, and still less if you’re Atlético.” For years, though, winning anything seemed impossible, which is why they never blamed him for going. In fact, they encouraged him to; they loved him, so they set him free. His only other title was the Second Division, 16 years ago – and that too helps to explain his impact, why Sunday mattered so much.

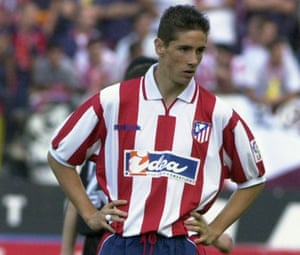

When Torres returned, Diego Simeone insisted he had signed the footballer not the icon, but that is what he is. Just in footballing terms, his departure is not so traumatic. Torres, though, is not just a footballer. He is The Kid from Fuenlabrada, the youth product and fan, who appeared when they were relegated to the second division, the embodiment of hope, their only hope. One little year in hell, Jesús Gil called it, only it turned out to be two but Torres led them back, became the youngest ever captain, and leaving took longer than anyone imagined. He turned down Real Madrid. He embraced and embodied Atlético’s identity, understanding and expressing it better than anyone, the pitch, tone and sentiment invariably perfect.

He suffered but waited; when he walked, it wasn’t just with their blessing but their gratitude. He was too good for this team, they knew; they convinced themselves that it was as if he hurt more than they did and didn’t stop supporting him. Liverpool shirts appeared at the Calderón. When he returned with them, both sets of fans chanted his name. When he returned properly, they were delighted. At his presentation over 35,000 were at the Calderón. He was always acutely conscious that he hadn’t actually done very much, almost a little embarrassed at how well they treated him. “You made me the happiest person in the world,” he said on Sunday. “I remember that he asked what he had done to deserve that when he came back,” Gabi said this week. “Well, I ask what we have done to deserve having you as the greatest exponent of Atlético around the world.”

A lot had changed since he had been away, since Simeone had arrived. When he scored his first goal Jean-Francois Hernández was among his team-mates; when he scored his 100th, Jean-Francois’s son Lucas was. He’d been away and come back and in the meantime Atlético started to win. He surpassed 100 goals, but from his return until Thursday they didn’t win again. Mostly, he embraced a secondary role, although the sense he could offer more ultimately hastened his departure. He lifted the trophy, delighted, but had only been on the pitch a couple of minutes.

Torres talked about the Champions League final in Milan as the game of his life; they were playing Real Madrid, the club where, he once insisted, “they don’t feel their football”, and lost on penalties. But at least they had played in a Champions League final, and that was unthinkable before. Which didn’t hurt any less but shouldn’t be forgotten and he was a reminder, so important precisely because he had been there in the bad times as well as the good. As well? Instead.

“Now that we win,” Iñako Díaz Guerra wrote, “we have to remember who we are. And that’s what Fernando’s there for. It’s not that he’s the veteran who came on to waste time and treated it like a gift; it’s not that he’s the star who won the World Cup and the Euros but never felt so fulfilled as when he won the Europa League as a bit-part with Atleti, his Atleti; it’s not a star saying goodbye, it’s our historic memory.”

Raised on Germany Street, the country against whom he scored the winning goal at Euro 2008, first taken to the Calderón by his grandfather in January 1995 to see Atlético draw 1-1 with Compostela, Torres recalled going to school in Fuenlabrada, “almost always pissed off because we had lost”, feeling like a lone Atlético in a place dominated by them, wearing his tracksuit in defiance. On Sunday, he walked out for his last ever game, knowing Atlético were going to finish ahead of Real for only the second time this century.

Atlético end the season having let in just 22 goals in 38 games. He left after they let in more than a quarter of that in one game. Things had changed, alright. “I never needed a trophy to feel like the most loved player in the world,” he said on Sunday. By then, at last, he had one, 17 years after his debut.

Outside the Wanda Metropolitano, a giant shirt was there for fans to sign. Photographs were lined along the concourse outside, an open-air Torres museum. He walked on for the last time as captain, carrying Nora, Leo and Elsa with him, his shirt, like those of all his team-mates, embroidered with the slogan: from Kid to Legend. A huge mosaic delivered the same message. They chanted his name. They lifted from their seats when he raced into the area, only to shoot wide, and again when he put an effort into the side netting. Then it happened: they roared when Ángel Correa laid it on a plate for him to score. There was another when he got the second, racing through to finish. Running into the crowd, he disappeared under the bodies.

On his last night at the Calderón, he had scored twice. On his last night as an atlético, here he was again: two goals, ahead of Real Madrid, a winner at last. But going now, just like Iniesta who was in tears in Barcelona. Even the DJ and his abysmal music couldn’t entirely ruin it. There was a guard of honour and a joint ceremony with Prieto at the start. At the end, after he departed with 10 minutes to go, almost ceremoniously handing over the captain’s armband to Leo Messi and sitting in tears on the bench, he was lifted by team-mates and thrown into the air. He took to the microphone to offer one last: “Visca Barca! Visca Catalunya! Visca Fuentealbilla!” “I’ll always tell the story of the day I was at Iniesta’s farewell,” Ernesto Valverde said.

In Madrid, they’ll talk of the day the Kid left. Torres went down the tunnel, and returned, team-mates giving him a guard of honour. Opponents Eibar applauded him too. No one had left, the place packed, but there was silence as the video played, a freckled kid with a blond mop appearing on the screen. “I’d like to start with those in the ‘third tier’,” he said, looking up beyond the stand in front, to the heavens, “especially Luis Aragonés, who showed us what Atletico Madrid is, and to my granddad …”

His voice broke, tears appeared in his eyes. Gripping tighter, he pressed on: “… who gave his grandson the greatest gift you can give, which is to an atlético …”

With every line – his parents, his wife and children, staff, team-mates – Torres seemed to swallow harder and the pauses grew longer, filled with song from the stands. “Today is the last day. It’s been over 400 games and it’s very hard knowing that this is the end,” he said. Then he started crying. As he circled the pitch one last time, they sang Atletico’s theme, a capella. And then, like Iniesta, he was gone.

Talking points

• All that and it comes down to this … nothing, really. For the first time, La Liga went into the final day with everything sorted. There was nothing to play for, unless you count the battle to be best of the Basques – Eibar for the first time. No relegation, no European places, no Champions League, and definitely not the title, which had been wrapped up early enough that they even managed to present Barcelona with their trophy in the season they actually won it.

• Speaking of the Basque country, this is the second worst season in Athletic’s history.

• It wasn’t just Iniesta, Prieto and Torres saying goodbye – already quite a hit in a single day. Among others, there was also Joaquín Caparrós, Asier Garitano and, although no one said so, Gareth Bale, scoring on what is probably his last game in Spain – at the stadium at which he scored his first.

Quick guide La Liga results and final standings

Celta 4–2 Levante, Leganés 3–2 Betis, Las Palmas 1–2 Girona, Málaga 0–1 Getafe, Sevilla 1–0 Alavés, Villarreal 2–2 Real Madrid, Valencia 2–1 Deportivo, Athletic 0–1 Espanyol, Atlético 2–2 Eibar, Barcelona 1–0 Real Sociedad.

Champions: Barcelona

Other Champions League places: Atlético, Madrid, Valencia

Europa League: Villarreal, Betis, Sevilla.

Relegated: Deportivo, Las Palmas, Málaga.

Top scorer: Messi, 34.

Top scoring Spaniard: Iago Aspas, 22.

Zamora: Jan Oblak.

| Pos | Team | P | GD | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barcelona | 38 | 70 | 93 |

| 2 | Atletico Madrid | 38 | 36 | 79 |

| 3 | Real Madrid | 38 | 50 | 76 |

| 4 | Valencia | 38 | 27 | 73 |

| 5 | Villarreal | 38 | 7 | 61 |

| 6 | Real Betis | 38 | -1 | 60 |

| 7 | Sevilla | 38 | -9 | 58 |

| 8 | Getafe | 38 | 9 | 55 |

| 9 | Eibar | 38 | -6 | 51 |

| 10 | Girona | 38 | -9 | 51 |

| 11 | Espanyol | 38 | -6 | 49 |

| 12 | Real Sociedad | 38 | 7 | 49 |

| 13 | Celta Vigo | 38 | -1 | 49 |

| 14 | Alaves | 38 | -10 | 47 |

| 15 | Levante | 38 | -14 | 46 |

| 16 | Athletic Bilbao | 38 | -8 | 43 |

| 17 | Leganes | 38 | -17 | 43 |

| 18 | Deportivo La Coruna | 38 | -38 | 29 |

| 19 | Las Palmas | 38 | -50 | 22 |

| 20 | Malaga | 38 | -37 | 20 |