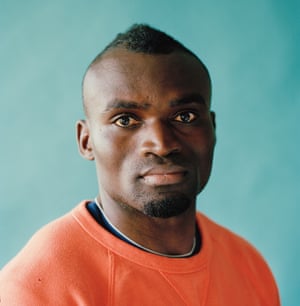

I first met Jimmy Thoronka in a London park in March 2015. He had been homeless for around five months, and a stranger who knew my work as a reporter had suggested we meet. Jimmy’s case was highly unusual: a gifted athlete, he had vanished after competing at the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow the previous summer, when he ran in the 4x100m relay for Sierra Leone. West Africa was then in the grips of the deadly Ebola crisis and, fearing for his life, Jimmy had overstayed his visa, travelling south from Glasgow to London. For a few months, he had a place to stay; but when that came to an end, he had found himself on the streets.

Over the years, I have interviewed many asylum seekers and people seeking protection in the UK, as well as many homeless people. But there was something different about Jimmy: a heightened vulnerability. While he may have got by on the streets, the 20-year-old seemed to lack survival skills and a sense of initiative. He was also very thin: when he removed his trousers to reveal the tracksuit he wore underneath, it was a shock to see how far his hip bones protruded. But, despite his hunger, Jimmy had been running on the park’s paths whenever he had the energy, or working out in the free outdoor gym. “I need to keep training,” he explained as he walked me around Burgess Park, his roofless home.

For months, Jimmy had survived by begging, or carrying people’s heavy shopping in exchange for money to buy the cheapest bread or a bag of chips. He washed himself and his few clothes, pilled from over-scrubbing, in the public toilets, then spread them out to dry on the icy grass.

Sometimes, a man he had met allowed him to sleep on a chair in his flat; Jimmy would wait patiently outside in the cold until he got home, often very late. On the days the man didn’t return, Jimmy travelled from night bus to night bus, dozing fitfully and trying to stay warm. When he hadn’t scraped together the money for the bus, he slept in the park. In his small black rucksack, he carried his clothes, a badly chewed toothbrush and a half-empty packet of paracetamol he had purchased in a pound shop. “I took an overdose because I wanted to end my life,” he told me, apparently unaware it would take more than that. “I was just moving around – I had no future.”

Shortly before he became homeless, watching TV in a friend’s flat, Jimmy learned that his mother had died of the Ebola virus: an African news channel reported that Jelikatu Kargbo, a senior nurse at a police-run hospital in Freetown, had been among a number of people infected while treating patients. It was a devastating shock: Jimmy had planned to return home once the Ebola crisis had abated; now he had no one to go back to.

At our first meeting, I had no idea if Jimmy was who he said he was. I began to make checks by phone with athletes and officials in Sierra Leone. Several confirmed that Jimmy had not returned home after the Commonwealth Games; no one knew where he was. I watched YouTube footage from Glasgow, which showed Jimmy looking fit and happy alongside his fellow athletes, all dressed in navy-and-white striped robes with green hats. He looked confident and carefree as he grinned into the camera.

I called the president of Sierra Leone’s athletics association, Abdul Karim Sesay, who told me Jimmy was a very gifted athlete “and an all-round nice guy. Everybody likes him. He’s not just a sprinter – he’s Sierra Leone’s number one 100m sprinter. He has the potential to be one of the best in the world.”

Jimmy had omitted to tell me his top ranking. I asked Sesay if Jimmy’s mother had died from Ebola.

“Yes, it’s very sad,” he said. “They’re all gone.”

“What do you mean, all?”

“His whole family has been wiped out by Ebola,” he replied. Jimmy had mentioned only his mother, who adopted him when he was five; he seemed unaware that he had also lost three sisters and a brother.

In a cafe near Burgess Park, I called Sesay and he and Jimmy spoke. It was clear from their conversation that the person sitting next to me was Jimmy Thoronka. He remained still and expressionless, but when Sesay explained that Jimmy’s family had died from Ebola, rapid tears fell into the polystyrene box of chicken and rice I had bought him. Kargbo had unwittingly passed the infection to four of her children, along with other members of the extended family; only one of her daughters, Musu Senesie, had survived. She and Jimmy were almost the same age; they used to do their homework together.

Soon after that, the Guardian ran my article and a short film about Jimmy’s case. The response was overwhelming. Theresa May’s “hostile environment” policy – a deliberate Home Office strategy of making life as difficult as possible for people without leave to remain –was entrenched since 2010, but readers were overwhelmingly positive and supportive. Jimmy had overstayed his visa, yes; but nobody could accuse him of living off the state or working illegally.

Practical offers of help flooded in. People offered spare rooms or running gear; a New York professor thought a sports scholarship might be available at his university. An entrepreneur called Emma Sinclair wrote: “ANYTHING he needs. I bet if you can’t get it, I can try. Supplements, if he feels in pain or wants protein powder or sports stuff. Anything. Desperate 4 the man to have anything he wants!” She was as good as her word and continues to support Jimmy. Another Guardian reader, Richard Dent, set up a GoFundMe page which went on to raise more than £30,000; in all, nearly 2,000 people donated money. Dent set up a trust, giving Jimmy access to £100 a week for basic living expenses. The University of East London offered a sports scholarship.

At the time, Jimmy was completely unaware of this wave of kindness. He had no email address or internet access on his battered Nokia phone. Hoping the news might lift his spirits, I arranged to meet him under the clock at Waterloo station later that day.

I waited and waited, but he didn’t show up. I kept calling his phone: no response. We knew there was a risk that the publicity would bring him to the Home Office’s attention, but Jimmy had accepted that, saying, “What other options do I have?”

Eventually someone answered his phone – a police officer.

“That didn’t take long,” I remember saying, assuming he had been arrested because of the article. But it emerged that Jimmy had been arrested purely as a result of that phenomenon, “running while black”. Plainclothed police were investigating drug dealing and burglary in the area, and had stopped and searched Jimmy, without explanation, when they saw him running. He was sprinting because, on his way to meet me, he had left his bag in the park and was running back to get it. When Jimmy gave officers his name, he came up as an overstayer. He was arrested, held in a cell at Wandsworth police station and told he would be put on a plane back to Sierra Leone imminently.

Later, Jimmy was allowed one phone call. When he rang me, I realised that I was both his first and last resort. I hardly knew him, but he had no one else. He was agitated and badly shaken. “I’m not OK,” he repeated.

While being held, Jimmy was offered the opportunity to claim asylum, meaning the Home Office would consider whether he could stay in the country. He lodged a claim based on the risk of contracting Ebola if he returned to Sierra Leone, and was moved to temporary Home Office accommodation near Heathrow airport. By then, the epidemic had been declared the worst ever outbreak of the virus, leading to more than 11,000 deaths in six countries. It was highly likely that, had Jimmy gone home to his mother, he would have died with his family.

After his release, Jimmy seemed calmer but desperately quiet and sad. His voice was so soft, you strained to hear him. He knew his future in the UK was far from certain.

Oliver Oldman, a solicitor at the London firm Bindmans, agreed to represent him, and advised Jimmy to apply for leave to remain rather than asylum. This seemed more likely to succeed, though it meant Jimmy had to move out of his Home Office accommodation and was homeless once more. For three months he took up an offer of a place to stay that came via entrepreneur Sinclair; after that, his only option was to go back on the streets. The thought of him moving back to Burgess Park was unbearable. My sister agreed he could stay with her family, and after a while he moved in with us – my partner (and Guardian writer) Simon Hattenstone and our adult daughters Alix, then 24, and Maya, then 22. I stopped writing about Jimmy: he was now part of our lives, much more than another news story. I wanted him to be safe, to smile again.

***

It was the start of a long and often cruel journey, covering more than two years of legal argument and court hearings, compounded by unexplained delays, reversals and refusals from the Home Office. We were witnessing at close range how May’s hostile environment policy played out, and the psychological toll it took.

Jimmy was already in a traumatised state. His mother’s death, and that of his siblings, was the second family he had lost: his birth parents had died in the country’s protracted civil war before he was adopted from a War Child camp at the age of five. Jimmy remembers little of that time, beyond playing football and being given a kind of porridge to eat.

Kargbo was a strict but loving mother, Jimmy says, a single parent who was fiercely protective of her five children. “She would tell us off if we did something wrong, but she also did everything for me. One time, at school, some of the children teased me and called me an orphan. She went straight in and told the children that if she caught them using that word about me again, she would beat them with a stick.”

Now, in the UK, a consultant psychiatrist assessed Jimmy as in a “chronic traumatised state”, suffering from night terrors and PTSD as a result of these multiple bereavements. “His current immigration status and the uncertainty and stress of proceedings acts as a major ongoing factor causing deterioration and preventing recovery,” concluded his report.

Oldman raised this with the Home Office, as well as telling them about the offer of a sports scholarship and Jimmy’s athletics talent, which he argued would be an asset to the UK. He added that Jimmy’s unique circumstances were “deserving of compassion and the exercise of discretion by the Home Office”.

But the Home Office disagreed. An eight-page decision issued on 29 September 2015, on the department’s distinctive beige paper, was headed, in large, bold type: “Your application for leave to remain has been refused. You must now leave the United Kingdom.” The letter went on to warn of dire consequences – fines, detention, imprisonment – if Jimmy didn’t go. Every argument put forward on his behalf was dismissed.

At our house, Jimmy lay in bed with a sheet pulled over his head like a shroud. He refused to eat, becoming so thin it was hard to know if he was in his bed or not when I passed his door. He wept and whispered, “I want to join my mother.”

Extremely concerned, Oldman asked the psychiatrist who had assessed Jimmy to summon the local mental health crisis team to his bedside. They recommended admission to a psychiatric hospital, where he was placed on suicide watch. During our visits, Jimmy was quieter and thinner than ever. He began to look translucent, like a spectre who might glide through walls at will.

After 19 days, Jimmy’s condition improved slightly and he was released back into our care. He was prescribed antidepressants and referred to a complex trauma unit. But the psychiatrist there said it wouldn’t be possible to start a prolonged course of therapy – not until his immigration status was clear; he would be too anxious for the treatment to work.

Back at home, there were fleeting moments when Jimmy’s mood lifted. He was wary and extremely diffident, but slowly he was becoming part of the family. He developed a liking for certain English foods, apple crumble and baked potato with baked beans, although he would also fry plantain sliced into perfect diamond shapes; occasionally he made foufou with ground cassava. He eschewed alcohol, smoking and drugs; his running coach had told him never to touch them, and he had long followed his advice. He overhauled our tiny garden and rescued a broken sewing machine he found in a cupboard, carefully repairing it. He began patching up and sometimes redesigning the family’s clothes. While the rest of us paid little attention to our shoes, Jimmy scrubbed his with a little pink brush and a square block of white soap. His footwear was always pristine. He began to attend a local African church.

Jimmy was also invited to join a group of sprinters trained by the leading UK Athletics coaches Lloyd Cowan and Clarence Callender, running at the eight-lane Mile End track in east London several times a week. And, despite his low mood, he somehow propelled himself to most sessions. It was the one thing that always made him happy.

Once, I asked him when he first realised he had talent. Running errands, he said. “If Mum needed salt or something from the shop, she always asked me to go because I could run the fastest.” His mother used to buy him a pair of trainers at the beginning of each school year and warn him not to get them dirty. “So I wore the trainers for school but I never ran in them. I ran barefoot.” Sometimes Jimmy crept out early in the morning to train before it got too hot.

He began winning school competitions in his early teens, but when he told his mother about his dream of becoming a top sprinter, she was far from impressed. “She tried her best to put me off. She really wanted me to study to become a doctor or a lawyer, but in the end she had to accept it.”

After Jimmy’s release from hospital, his solicitor made further submissions to the Home Office based on his poor mental health. Once again, officials refused his case; but this time he was granted an in-country right of appeal which would be heard in front of an independent judge in the immigration tribunal – only not for more than a year.

While he waited, Jimmy hoped he might be able to take up his sports scholarship; it was one way of ensuring he was no burden on the taxpayer. The University of East London made inquiries with the Home Office: could Jimmy begin his studies? The answer was a curt no, not until his immigration status was regularised – a punitive decision that left Jimmy deflated.

At the beginning of 2017, Simon and I accompanied Jimmy to court for his hearing. It was a moment he had both dreaded and waited for, but the Home Office presenting officer immediately asked for it to be adjourned: she had not read the papers relating to the case. The seven witnesses who had come to court were told they would have to come back in March.

Two months later we reconvened. Again, the Home Office representative, this time a barrister, had not read the papers; again an adjournment was requested. This time it was denied, and Jimmy’s case was heard. He spoke softly, and some of the witnesses cried as they described what he had been through. Two months later, in May last year, the judge ruled decisively and comprehensively in his favour.

Jimmy did not smile when he got the news. He knew it was possible the Home Office would appeal, and sure enough they did – arguing that the judge had made an error in law, by not giving due weight to certain legal points. For the Home Office, this was just another case. For Jimmy, it was a protracted chokehold that was squeezing the life out of him.

Permission for the Home Office to appeal was granted last November, and in February a second court hearing took place. Again Jimmy wore his carefully ironed white shirt from Tesco; again he was rigid with fear. A more senior judge heard the Home Office’s request to appeal. Initially, he reserved judgment, meaning more weeks of worry. But eventually he rejected the Home Office’s arguments, just as the first judge had done.

Three years after Jimmy’s first application to the Home Office from that Wandsworth police cell, on 20 April 2018, he was granted leave to remain. Some of that delay had been due to logjams in the immigration tribunal process, which meant it took more than a year for his initial appeal to be heard. But the Home Office determination to prosecute the case as hard as it could, despite knowing of Jimmy’s traumatised state, significantly prolonged the agony. The fact that the government’s initial refusal of his case triggered hospitalisation and a suicide watch was no deterrent. What appeared to matter far more was sending tough messages about migration to swing voters: that this government is not so much robust as positively steel-capped. In response to the Windrush debacle, Amber Rudd last month admitted that sometimes the Home Office “loses sight of the individual”. It was a profound understatement.

Jimmy’s leave to remain is the start of a new chapter rather than a happy ending. He still badly needs medical help, but has to go back to the start of the referral process. A call to the NHS complex trauma unit to inform them that he was now able to start treatment was greeted with the news that the case had been closed. Jimmy has had to get a new referral and a second assessment before any treatment can begin.

Meanwhile, Jimmy is still hoping to embark on a degree – in computer studies – at the University of East London in September. In Freetown, his experience of computers was limited to watching YouTube footage of sprinters in internet cafes; since coming to the UK, he has developed a passion for coding and an interest in network security. He volunteers at the university already, assisting a staff member who supports students with their computer studies. “My dream has always been to be the best sprinter,” he says. “But an even bigger dream is to go to university and pursue my education.” Meanwhile, he has received another setback: as a person with discretionary leave to remain, he is not entitled to a student loan.

He continues to train with elite runners, and at last will be able to travel with them to international competitions. His coach Clarence Callender speaks of him in glowing terms, as a generous, “open-minded” young man. “Jimmy has progressed enormously in a short time period,” he says.

And while there has been much bleakness on Jimmy’s journey, he has also encountered enormous kindness along the way – from new friends, fellow athletes and coaches, members of his church, Guardian readers and university staff. But the loss of two families followed by three years doing battle with the government have not left Jimmy unscathed. He continues to be terrified of the Home Office, and often seems grey and tearful. After he won his appeal, he was summoned to a Home Office reporting centre and subjected to questioning by both UK officials and diplomats from Sierra Leone, who queried his nationality – bizarre, considering he has competed as an international athlete. To date, the Home Office has declined to offer an explanation for this meeting.

Jimmy continues to be low. But he recently dug up our back garden, a tatty patch of grass, and planted it with new seed. As spring advances and the days grow longer, the grass has become lush and thick, a vivid green. It’s not much, but it’s something that has made him smile.

• Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).