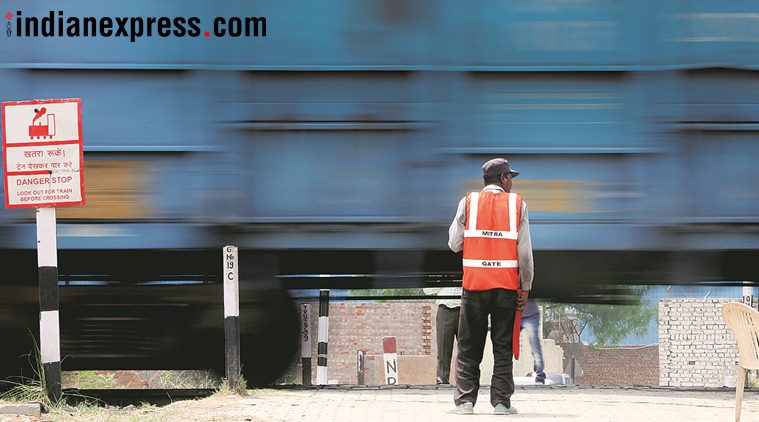

Around 70-80 trains pass by during the 12-hour shift of Satpal Singh, that he spends mostly sitting on a chair in the open. The 32-year-old says tackling drunks is the biggest challenge. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Around 70-80 trains pass by during the 12-hour shift of Satpal Singh, that he spends mostly sitting on a chair in the open. The 32-year-old says tackling drunks is the biggest challenge. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

It is 7 am and Satpal Singh is looking at a long 12 hours ahead. The ‘gate mitra’ at a railway crossing near Rohtak in Haryana, he is required to be at his post till 7 pm, with officially no breaks. Today, he doesn’t have his lunch either as his wife is away along with their three children. “They have gone to our village in Farrukhabad (Uttar Pradesh). My neighbours cook for me these days. They will send the lunch with someone later,” says the 32-year-old.

Recently, 13 children were killed after a train hit their school bus at an unmanned level crossing in Kushinagar near Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh. Each such crossing in the country is supposed to have two gate ‘mitras’ or ‘friends’ — one for the day and one for the night — to ensure safety and prevent accidents.

The Railways launched the Gate Mitra initiative in 2016. As per Northern Railways Chief Public Relations Officer Nitin Chowdhary, the idea was to “enhance safety and provide employment to local residents”. A railway official who doesn’t want to be named puts the number of unmanned level crossings in the country at 3,479, adding, “Our aim is to eliminate all by 2018. We eliminated 1,565 in 2017-18.”

Satpal Singh (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Satpal Singh (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Hired through contractors, the gate mitras make Rs 12,000 a month, without any benefits or weekly offs. Satpal, who didn’t study after failing his Class 10, was hired in 2008. Before this unmanned crossing between Bahadurgarh and Ghewara in Haryana — ‘Crossing No. 19’; the numbering done by zonal railways — he was posted at the Barola crossing near Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh, where he lived at the time.

Satpal cycles to the Ghewara crossing, which is just 5 minutes from a house he has rented in the village. The rent is Rs 3,200 per month, and Satpal’s brother, who shares the two-room house with Satpal’s family of five, pays half of it.

Dressed in a striped shirt, loose black trousers and a cap to shield him from the sun, Satpal takes his position in a plastic chair, which is propped up by bricks due to a broken leg, along the tracks. His ‘official gear’ includes an orange reflector jacket (which glows in the dark), a green whistle and a red flag.

There is a small structure, 4 ft by 4 ft, allotted to the gate mitra of this crossing. The ‘room’ is open on one side, so that the track is clearly visible from inside. But with a tin roof, kuchcha flooring and not even a fan, it gets unbearably hot in the summers.

Satpal says he hardly ever sits inside. “I can’t sit under the trees either because I might miss a train. So I sit here,” he says, pointing to the chair, which will soon have sun directly overhead. He stocks his “belongings” in the ‘room’, including his bicycle, a couple of notebooks given by the Railways to make official notings, and a lantern for when night falls.

Essentially, his job involves counselling people on safety and stopping them if a train is approaching, Satpal says. “On an average, I intercept around 10 people every day. I have to write their names in a notebook and submit this to senior officials who come for inspection every two days. I tell people I am here for their safety, and that they should always check for trains before passing the crossing.”

However, says the 32-year-old, it is easier said than done. Not everyone listens to him. “People are strange. They know I am here for their safety but sometimes, they get violent and tell me to let them pass even when the train is close,” he comments, looking at his silver-dial watch to check which train will cross next. “A passenger train will come in some time. I don’t have a schedule, but now I know the trains that pass.” As part of his duty, he has to make a note in his books of the trains that pass by daily.

While the anger of the people doesn’t scare him, Satpal adds, he has to be cautious. “I have been living here more than two years. I consider myself a local now and I tell people that when they argue with me. I have heard stories of people beating up gate mitras if they don’t let them pass.”

He talks of one such incident, at ‘Crossing No. 66’. “It was a manned crossing, with gates on both sides. The assaulters split open the gate mitra’s head. Someone showed me pictures of it on their phone. I don’t have a smartphone, or I would have shown you,” he says, looking at his watch again.

At this point, a train can be heard approaching. It is 11 am and Satpal says it must be the Delhi Rohtak MEMU. On full alert now, he gets his red flag from the room and puts the green whistle hanging around his neck to his lips, as he glances on both sides to check if there are people approaching.

As the train comes near, he starts blowing the whistle, insisting the driver can hear it. He continues to blow it as the train with huge milk cans hanging out from the windows and packed with passengers speeds across.

Two men clad in dhoti and kurta wait on their motorcycle for Satpal to allow them to cross. “The government should put a gate at this crossing soon. Some day, something will happen. This gate mitra is here, but how much can you expect one person to do?” says 32-year-old Ranbir Singh, a farmer from Tikri village, who passes the crossing almost every day.

Next comes a tractor with three men. Satpal walks up to them to say they should be careful. “I am here only for your safety. Whenever you cross, look on both sides.”

The three men feign interest in what Satpal is saying, but their impatience is evident. As they hurry away, Satpal shrugs, “Logon ko bhalai nahin samajh aati. Unko bas jaldi hoti hai nikalne ki (People don’t understand something that is for their own good. They are just in a hurry to cross).”

Waiting for the next train to arrive, after which he will eat his lunch, Satpal says the biggest challenge is tackling drunks. “You never know when they might get angry. People here have guns, who knows when one might take it out?” he says, advocating a complete ban on alcohol as “a solution to every problem in society”.

Around 1 pm, a goods train trundles by, and Satpal repeats the drill of blowing the whistle and holding up the flag. “Around 70-80 trains cross this spot in the 12 hours that I spend here,” he estimates. “I have to be alert at all times. I can’t afford to relax at all.”

By now, his lunch has arrived, brought in a steel tiffin box by a neighbour. It contains rotis with spinach, and one green chilli. Satpal, who admits he is very hungry, gulps down his first proper meal of the day, seated inside the ‘room’. He says he can take out only around 15-20 minutes for lunch, scheduling it to train timings, before returning to work.

As he eats, Satpal complains about the lack of arrangement for even water or a toilet at the crossing. “I can manage without a toilet, we are used to it. But there is no water too, and in this heat, one needs water. There is a handpump which someone got installed recently for their farm, but water from that is khaara (salty) and the factory nearby (that ironically makes handpumps) refuses to give me water,” he says.

On hearing another train approaching, Satpal goes back to the chair. As the Kurukshetra passenger train whizzes past, he says he plays Hindi songs on his phone to pass the long, often boring hours. Headphones make a person “deaf”, he insists, and so he hears them over his phone speaker.

At other times, Satpal lets his mind wander to where the people on the trains passing by might be going. However, he sighs, he is aware that for them, he is no more than a cipher. His eyes fixed on the fast-disappearing back of the Kurukshetra train, soon just a foggy mirage in the afternoon sun, Satpal says, “People look at me as if I don’t exist. They can see me from the train, but they don’t react at all. It’s like I am not here.”