Priya Ravish Mehra (1959-2018)

Priya Ravish Mehra (1959-2018)

Last month, as three rafoogars from Uttar Pradesh’s Najibabad, a hub for darners, introduced visitors at India International Centre Annexe gallery to their skillful art of darning, the absence of textile artist, weaver, and curator Priya Ravish Mehra, could be felt by many. They were working with torn pieces of over two decade-old shawls, repairing the gaps to make the defect invisible. A month after bringing to the Capital her exhibition ‘Making Visible: The Rafoogars and the Journey of a Shawl’ to highlight the often-neglected skill of rafoogiri, the designer breathed her last at her residence on Saturday.

Mehra’s battle with cancer for over 13 years, and her body’s attempt to heal itself was an analogy she used while talking about her textile-based artwork. In our last meeting with Mehra, she said, “Much like how they repair a cloth, we heal our bodies. Throughout our life, we have to keep mending and restoring it to help it go further and give it strength.”

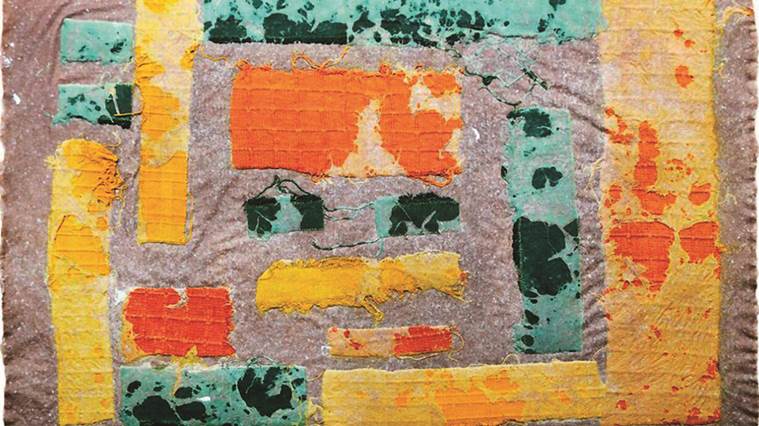

A textile exhibit by Priya Ravish Mehra

A textile exhibit by Priya Ravish Mehra

Gallerist Tunty Chauhan feels that it was ironical that Mehra’s last solo show at Gallery Threshold was titled ‘Presence in Absence’. “Priya was a braveheart, who lived her life to the fullest. Her art was her journey,” says Chauhan. Mehra’s practice, over the last few years, has centred around the theme of preserving, repairing and restoring. Her body of work, from 2014 onwards, displayed at Threshold last year, were made using paper pulp, plant fibres, and discarded cloth pieces. An antique jamawar piece seamlessly blended into a white paper mixture, plant fibres like twigs merged with paper pulp, while fragments of jute fabric played around with plant pulp in the artist’s frames.

Mehra had studied fine arts (textile) at the Visvabharti University, Santiniketan, followed by a stint with tapestry weaving from the Royal College of Arts in London, and West Dean College, Sussex, on Commonwealth Fellowship and Charles Wallace Trust scholarship. Textiles, thus, became her medium of choice for her work, for life.

Soon, memories of seeing skilled darners visiting her house in Uttar Pradesh while growing up as a child, became difficult to erase. Flashbacks of them bringing pashmina shawls, a jamawar, or a heavily embroidered sari to display their skill at hiding and mending the defects, propelled her to take up the cause of the invisible form of darning. She uncovered a startling discovery of how the darners would find a mention in Mughal writings, yet their work remained largely undocumented. Nadeem Anver, a rafoogar, who worked with Mehra for nine years, says, “She was someone who did a lot for us. Before her, nobody cared about us. People would get their work done, pay us and ask us to leave. They would not see the hardwork involved. I don’t know if anyone will help or fight our cause in the future.”

The subject of darning became her muse for more than a decade, and was the prime focus for several of Mehra’s interactive workshops. Her paper ‘Rafoogari of Najibabad’ at the 9th Biennial TSA Symposium in Oakland in 2004, and ‘Rafoogari — an Invisible Craft’ at North American Textiles Conservation Conference in Mexico in 2005, serve as prime examples. Mehra also restored and recreated the Eureka flag during the Commonwealth Games in 2006, when she participated in the Common Goods Project along with two Indian rafoogars at Ballarat Fine Art Gallery in Australia. Armed as a research consultant, she also travelled across Bihar and Gujarat for the ‘Saris of India’, as part of Ministry of Textiles’ research-based project, from 1987-1992.

Kochi-Muziris Biennale’s co-founder Riyas Komu highlights how Mehra visited the last edition of the festival in Kochi. He says, “She has been a keen follower of our festival though she was unwell. I have always seen her as one who had an interest in social issues. She was a fighter. It’s a big loss to our fraternity.”

Laila Tyabji, chairperson of Dastkar, echoes similar views on her Facebook post: “I first loved her work, and then came to love her. Her sensitive design sensibility was always available to our craftspeople, informally and in the in-depth projects she did with Dastkar, with the Jawaja Durrie weavers and the namda craftspeople in Kashmir. She mixed her unique aesthetic with practical common sense and humanity that the craftspeople immediately responded to.”

Much like the role of a darner who appears like a magician in our lives yet disappears after the cloth is mended, Mehra too became that captivating and enchanting figure for countless weavers and rafoogars in the country.