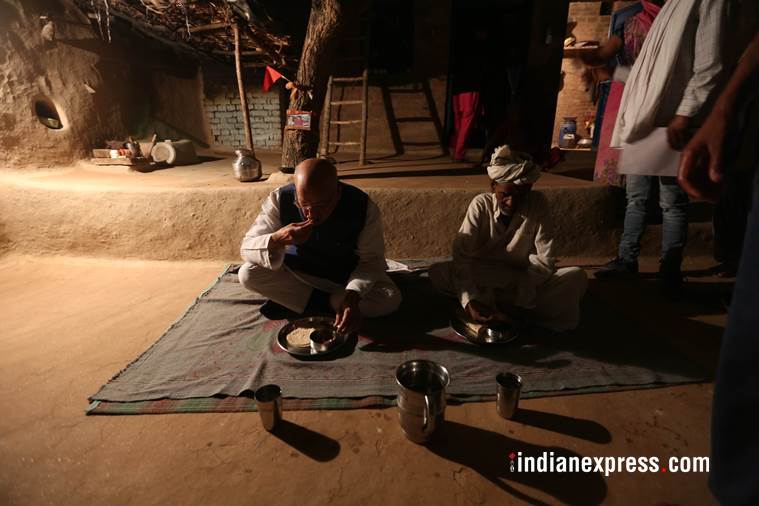

MP Bhagirath Prasad eats with Duli Chand, 80, selected to share the meal with him for being the oldest man in the village. The others watch on (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

MP Bhagirath Prasad eats with Duli Chand, 80, selected to share the meal with him for being the oldest man in the village. The others watch on (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

“Will the country make one of us PM?”

Guest: Bhind MP Bhagirath Prasad

Host: Raghubir Prasad; Durgapur village, Bhind

Ankita Dwivedi Johri trails MP Bhagirath Prasad in Bhind

Pratap Singh Lahari has a lot on his mind. Leaning against a wall of Ambedkar Mahavidyalaya in Durgapur village in Madhya Pradesh’s Bhind district on April 19, the 50-year-old is reading out a slogan to a ‘painter’ — ‘Naari ab majboor nahin, shauchalay ab door nahin’.

In the next hour, Lahari has scores of such slogans — ‘Bahu beti door na jaye, ghar mein sauchalaya banvaye’; ‘Mann ka mandir devalaya, tan ka mandir sauchalaya’ —painted across the college, the two schools in the village and on several kuchcha homes.

That’s one job done. But Lahari has a long list of others — get the roads cleaned, remove cow dung cakes, arrange a generator, set up a bed in the college principal’s office and get water for its toilet, decide the menu, and brief villagers on government schemes.

In 12 hours from now, Bhind Member of Parliament Bhagirath Prasad will visit Durgapur, an entirely Dalit village, as part of the BJP’s Gram Swaraj Abhiyan. “On April 18 I was informed that Bhagirathji will visit on April 20 and stay the night. I have been making arrangements and organising information on the schemes since,” says Lahari, listing matter of factly the duties he discharges of sarpanch, in place of his wife Geeta.

They have four children, the eldest 32 and the youngest 18. Like most of the 201 families of the village — 970 residents, all belonging to the Daure community — the Laharis rely on agriculture to make a living.

The violence that had followed the April 2 bandh called by Dalit groups against the ‘dilution’ of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act left four dead in Bhind — three Dalits and a Thakur. While there were no casualties from Durgapur, 50 of its residents had joined a protest in Daboh nearby.

Frying puris over a chulha, Leelavati says her husband applied for LPG a year ago (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Frying puris over a chulha, Leelavati says her husband applied for LPG a year ago (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

“70 years after Independence, Dalits are struggling for the most basic things. Hamaara behuda kaata ja raha hai (We are being cheated),” says Siya Saran, 53, who works as a labourer in Gujarat. “50-60 per cent of our men work as daily wagers in other states. Beehad mein zameen ubad-khabad hai (The land here is arid, uneven)… There is barely any farming,” says the father of three, adding, “Laws and schemes will not empower Dalits, opportunity will. We should be given that.”

Saran’s 23-year-old son Jayant participated in the Daboh protest after receiving a WhatsApp message. Almost every home in the village has access to Internet — giving youngsters a glimpse of both what they can have, and don’t. Durgapur’s literacy level, of 71.57 per cent, higher than Madhya Pradesh’s 69.32 per cent, also accentuates that gap.

So while the village may not have caste tension, and is represented by a Dalit MP, their problems remain, the residents point out: of jobs, water, power, toilets, homes.

Jayant says he has a diploma in computers, but works as a labourer. “Ensure the above and there will be no protests.”

After getting the slogans painted, Lahari gathers along with a small group under a tree to meet LPG cylinder contractor Parmal Singh Gurjar. As Gurjar ticks off the names with LPG connections in the village on his list (43 of 180 homes), he urges the crowd to visit Daboh the next day for the ‘Ujjwala Diwas’ function where Prasad will be chief guest. Those who have been waiting a year for LPG connections lose their cool. They vent their anger on Lahari, on this and other issues.

Gaya Prasad, 62, whose sons work as labourers in Gujarat, fumes about stray cows. “Hundreds of cows are dropped on the outskirts of the village at night, and ruin our crops. Sarkaar ne notebandi ki, par humein gaibandi chahiye (The government imposed demonetisation, but we want a check on cow population),” he shouts.

One of the PM Awas Yojana beneficiaries complains he hasn’t got full money (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

One of the PM Awas Yojana beneficiaries complains he hasn’t got full money (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Upendra Singh, 21, a BSc graduate and jobless, asks when he will receive the money for building a toilet (Rs 12,000 under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan). “We have spent close to Rs 30,000,” says Singh.

Villagers say toilets have been built in 40 homes under Swachh Bharat, but that because of water shortage, they are useless. “We have to carry at least two buckets from one of the village’s three handpumps every time we use the toilet,” says Upendra.

As the group moves towards the village centre, and a small Ambedkar statue, some men point to low-hanging wires. Durgapur got electricity in 2015 (through the Department for Welfare of SC/ST, OBC and Minorities), says 40-year-old Jagmohan Bablu, a farmer. “But we don’t get any power in daytime, only after 10 at night.”

Bablu is hoping to hear soon on his application for a pucca home under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. In Durgapur, six homes have been cleared under the scheme.

The 40-year-old is not satisfied with Lahari’s assurances. “There are close to a hundred Dalit MPs, but no one listens to us. Many people at the April 2 protest did not even know about the SC/ST Act but turned up to demand justice, opportunity… But what happened? Three Dalits were killed.”

Now the centre of all eyes, Bablu adds, “If people are really serious about Dalit issues, why don’t we have a Dalit prime minister? Will the country make one of us the PM?”

Like Lahari’s wife, the women of the village, most of them uneducated, are nowhere to be seen. Frying puris over a chulha, Leelavati, 56, a ghoonghat covering her face, says her husband applied for an LPG connection a year ago. Admitting the smoke and heat of the chulha hurt their eyes, Leelavati nudges her sister-in-law when asked about other issues facing women.

“We don’t have a toilet,” says the 45-year-old hesitantly. “We go once early in the morning, and then hold it till dark.”

On being asked her name, she smiles and, after a long pause, says, “Devi likh do (Write Devi).” Age? “Tees likh do (Write 30).” She has two sons, ages 22 and 20.

Like her, most women are reluctant to speak. Guddi, a mother of three, the eldest 20, who says she is 30 too, has an LPG connection but hasn’t dismantled her chulha yet. “It takes time to get a replacement cylinder,” she explains. Would she raise the problem with Prasad? Guddi is surprised. “The MP is visiting?”

***

Early morning on April 20, a Friday, life is moving at a sedate pace in Bhind town. Section 144 curbing assembly is still in place.

At MP Bhagirath Prasad’s ancestral two-storey home, the day has begun early. By 9 am, the 70-year-old Dalit leader has hit the road, along with a police vehicle.

Prasad used to be an IAS officer, who joined the Congress and contested for the first time in 2009. He moved to the BJP ahead of the 2014 elections. About the switch from the Congress, he says, “There was a lot of factionalism in the party.”

Prasad’s wife is Hindi author and Padma Shri awardee Mehrunnisa Parvez. They have four children, one of them an IPS officer. The youngest, 16, a son, is still in school.

On way to Durgapur, the 70-year-old meets two of the four victims of the April 2 violence, who complain about poor investigation and lack of relief. Many are concerned about the strain in the relationship with Thakurs since. A local BJP leader with royal links, Nripendra Singh, blames “3,000 men brought in from UP” for the violence.

Bhind Collector Ilayaraja T says false rumours regarding the SC/ST Act fuelled the violence. “It is the first time 15-year-olds were part of an agitation.” A senior officer calls the dominance of dacoits in the region, feeding on “strong sentiments of justice”, and the easy availability of guns as factors.

Prasad chooses his words carefully. “The April 2 protest was against the inherent inequality in our society. There is a craving for equality among the weaker sections, and the democratisation process involves some upheaval. Our endeavour should be to make the transition smooth, balanced, and oriented to the ideals of the Constitution.”

By the time Prasad makes his way to Daboh for the Ujjwala Diwas function, it is 4 pm. Nearly 300 people have been waiting since 11 am. While only 30 women are to get LPG connections, others are hopeful. As Prasad starts talking about the PM’s schemes, Kamala Devi, 30, a mother of two, says she has just been informed her name is not on the list. “How much longer do we wait?”

It’s after 6 pm when Prasad’s convoy finally arrives at Ambedkar Mahavidyalaya in Durgapur. It’s getting dark fast, and Lahari leads some men in a hasty ‘aadar-samman (honouring)’ ceremony. Prasad asks for files regarding the village and begins his round.

A banner of the ‘Asangathit Mazdoor Kalyan Yojana (a state government body for labourers to provide them access to government schemes)’ catches the MP’s eye. He asks whether the men of the village have registered. They all respond in unison: “No.” “We have 275 registered names with us,” insists a representative of the scheme.

Angry villagers counter saying they have never seen the representative before this. Prasad reprimands him and continues.

Next on the MP’s list are the six homes constructed under the PM Awas Yojana. At one of the homes, Umesh Kumar, 22, complains he hasn’t received the entire sum of Rs 1.2 lakh under the scheme.

When Prasad nears the Ambedkar statue, villagers demand a shed for it.

By now, it is completely dark, and mobile phones are fished out to provide the MP light. Prasad decides to stop at a house for tea, and is soon confronted by an angry youth. “Only six homes have been built (under the PM Awas Yojana). What about us?” he yells.

Prasad urges the youth to talk with “namrata (politely)”. He then pulls up the ‘Development Incharge (one per block of five villages)’, Ajit Barwah, and tells him to see to it that 50 more homes are built soon.

In the next hour, as Prasad, followed now by a growing crowd, some carrying lamps on their heads, manoeuvres his way through the village lanes, again the women stay inside, except a few.

Around 8 pm, as Prasad approaches the home of the sarpanch — a spacious, pucca home, the village’s biggest — the power comes on and a few homes light up. “Bas thodi der mein chali jayegi (It will go in a few minutes),” laughs a villager.

The MP settles down in a chair, and the discussion veers towards jobs and water. After listening for around 40 minutes, Prasad reassures, “This village has been chosen as an Adarsh village (model SC village) and Rs 20 lakh has been given. Another Rs 30 lakh will come. The onus is on the village heads to use the funds intelligently. The Prime Minister is doing everything for the poor.”

Lahari offers food, but Prasad refuses, saying he can’t eat at the “mahal-like” home. Lahari then suggests his neighbour Raghubir Prasad’s kuchcha home to eat and sleep in. Prasad lives there with his wife, mother and three children.

The food — roti and kathal (jackfruit) — however, comes from the sarpanch’s house, in a steel plate and bowl. Several youngsters rush back and forth from the sarpanch’s kitchen to Prasad’s home, laying down a mat, and carrying the food and water. A cot is also brought from the sarpanch’s home and set up in the open for the MP to sleep in.

As Prasad tucks into the meal, men gather around him and continue to talk about the lack of electricity. The only one who eats alongside Prasad is Duli Chand, 80, the oldest man of the village.

“Right now there is electricity, but the voltage is very low and the fan won’t work. Sansadji bahar hee soyenge (The MP will sleep outside)… But there will be mosquitoes and he will have to use the toilet in the sarpanch’s home,” says Raghubir Prasad, 35, adding, “I didn’t know he would spend the night at my home, I would have made arrangements.”

As a grateful Lahari thanks the MP for coming, his wife and sarpanch of three years, Geeta, looks on from inside the kitchen. After some time, she peeps out, and asks, “Do you need more rotis?”

***

“Iska kuchch hoga?”

Guest: UP Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath

Host: Dayaram Saroj; Kandhai-Mudhupur village, Pratapgarh

Sarah Hafeez trails UP CM Yogi Adityanath in Pratapgarh

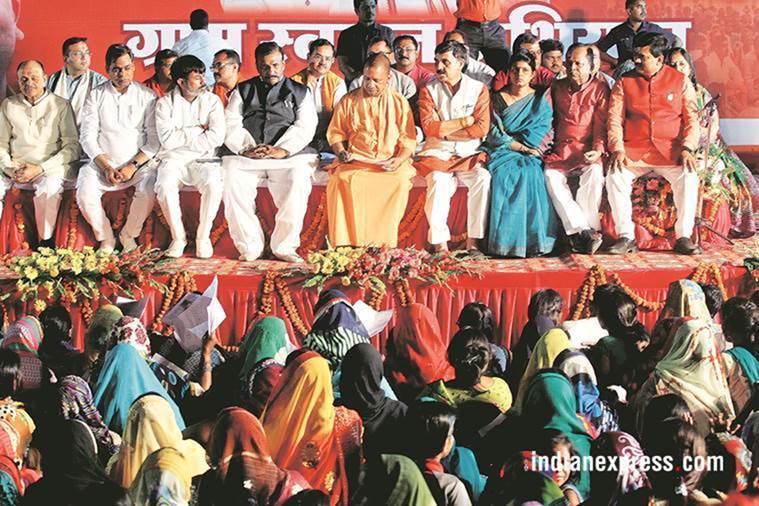

UP CM Yogi Adityanath at a ‘chaupal’, where he got the women to come closer to the stage to hear their applications (Express Photo by Anand Singh)Shiv Pratap Singh, officiating as Kandhai-Mudhupur pradhan in place of wife Archana Singh, starts tearing up recalling the previous night’s “disaster”. When he first heard the news, that Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath had chosen their village as the first to spend the night in as part of the Gram Swaraj Abhiyan, he was delighted at the “saubhagya (honour)”.

Thirty-two hours later, dabbing his eyes with a saffron handkerchief, the 58-year-old says, “Sab khatam ho gaya (It’s all over).”

With a population of over 12,900 as per the latest official count, Kandhai-Mudhupur is the third largest village in the upper-caste dominated district of Pratapgarh. At 48 per cent, OBCs form the largest chunk, while 18 per cent are Dalits.

At 2,300-odd, the village’s Dalit numbers qualify it for the BJP outreach plan.

However, for officials who worked round-the-clock for Adityanath’s visit, things went wrong from the beginning.

***

It’s 6.30 pm on April 23. The CM has just arrived in a chopper, at the end of a hectic day, after inspecting a grains godown, a hospital, a police station, and after meetings with district officials and another meeting with party members in Pratapgarh town.

Straight off the helicopter, he heads for a “chaupal (meeting)” on the grounds of BDSK Educational Institute, the largest of the seven schools in the village. Manager Ramakant Dwivedi says the school, with roughly 400 students from Class 1 to 10, was opened in 2016 to “stop young couples from leaving their ageing parents to educate their children in cities”. It got CBSE affiliation last year. While it has students “of all castes”, of its 16-odd teachers, one is a Dalit.

The grounds of the institute are lit with powerful yellow lights, and Shiv Pratap Singh insists electricity is not a problem, for any of the village’s 2,300 houses. “Our village has been fully electrified under various government schemes, including the latest, the Deen Dayal Gram Jyoti Yojana. There is supply for most of the day.”

Noticing the flowers covering the stage, Adityanath orders them removed and calls out to the women to come near. Women duck under a barricade to get to the stage, as men take the seats vacated by them.

Adityanath starts speaking about the benefits of government programmes. When villagers interrupt him with slogans of Jai Shri Ram, Adityanath isn’t pleased, telling the crowd to hear him out first.

But when the CM goes on to ask how many people have toilets under Swachh Bharat, the shouts begin again, growing into a roar as hundreds wave their hands saying “Ek bhi nahin (Not even one)”. After a short pause, Adityanath summons “all three”, the “DPRO (district panchayati raj officer)”, “CDO (chief development officer)” and “DM (district magistrate)”, to loud cheers.

Shiv Pratap Singh later admits money had not come through this year for 500 toilets under Swachh Bharat.

However, that is not the only complaint villagers have. While officials say 300 gas connections have been distributed in the village over the past year under Ujjwala Yojana, Prabha Devi says only eight of 115 families in her basti had got cylinders. “But even those people are using stoves because who can afford a cylinder?”

The men surprise him with their vociferous response to a question on Swachh Bharat toilets: “Ek bhi nahin” (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

The men surprise him with their vociferous response to a question on Swachh Bharat toilets: “Ek bhi nahin” (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

As jostling begins to hand over applications to the CM, he asks officials to collect the letters. Rekha Singh, 40, weeps as she hands over her plea, regarding the death of her daughter in a suspected dowry case. Gajender Yadav, 25, tries to hand over a disabled pension application, but fails.

Adityanath receives an angry response on other schemes as well. “Pradhan bees hazaar maangta hai (Pradhan asks for Rs 20,000),” shouts one man, when the CM refers to the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. “Bees hazaar, Bees hazaar,” others add in a chorus. Aditynath gets the DPRO to read out names of all the 136 beneficiaries of the scheme in the village, to reassure them that “the pradhan does not decide the list, officials do” — to little avail.

The 2016-2017 list of Awas Yojana beneficiaries for the village shows 68 Dalit families, and 26 in the general category. But in 2017-18, only one SC family got the funds of Rs 1.2 lakh. Says Shiv Pratap, “The Central government conducted a baseline survey in 2011 of beneficiaries (this was part of the Socio-Economic Caste survey conducted for the 2011 Census). Several are no longer eligible because they are richer. That is why, only one family was allotted a house last year. We are now drawing up a fresh list.”

Concluding the chaupal, the CM asks officials to hold a week-long camp to sort out the problems. He comments that it is sad that “even 70 years after Independence, government schemes have not reached the people”. “To a large extent this is because of lack of awareness, and for this a seedha samvad (direct approach) with people is necessary.”

Adityanath adds, “We will run an aggressive campaign to eradicate untouchability. Hamara samaaj jatiwaad, chhua- chhoot ko nahin manta (Our society does not believe in casteism, untouchability).”

Going on to praise Prime Minister Modi, he says, “Not the Congress, the BJP has been working for Dalits. If anyone has respected Baudhisatv Bharat Ratna B R Ambedkar, it is the PM.”

Around 9 pm, the CM heads to retired India Post employee Dayaram Saroj’s house for dinner. Shiv Pratap says the house was chosen as it was the “grandest” in the village and suited in terms of security. A cemented lane leads to a cement porch where Saroj’s municipal yellow house stands, one of the few pucca ones in the village. A rangoli with ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ etched on the clearing welcomes the CM, besides a green mat laid out for the guests to sit on, large halogen lights, sofas and a centre table.

“The problem with Dalits here is that they do not study. They spend all their money on living indulgently,” comments Shiv Pratap, himself an upper caste. “But Dayaram’s father, a tonga driver, worked hard and educated all his sons. One of Dayaram’s brothers retired as a government school teacher, another is a clerk in the Revenue Department. That is why the CM came to his house, and Dayaram made history.”

Adityanath and Saroj sit side by side on the green mat, flanked by local leaders and aides, and surrounded by camerapersons, to eat. The dinner includes rotis, bitter gourd, sponge gourd, mango chutney, dal and rice. An official admits mineral water has been arranged “as a measure of safety”.

Officers have been supervising the dinner preparations from 6 pm, with most of the food cooked by Saroj’s family members. Swati Singh, an upper-caste leader and UP Minister of Food Control and Women and Child Welfare, made the rotis, says Girdhari Singh, Amethi district BJP in-charge.

A Dalit resident, Sanjana, says it is an honour the CM chose a home from the community. “But it remains to be seen what will come of such dinners,” she says. “Everywhere we go, our money is swallowed up by a corrupt officer. Even the electricity connection we got cost us Rs 3,000, and we were given a bill of only Rs 1,650. Who should we go to for such problems?”

Md Farooq, a tailor, also identifies corruption and lack of development as the root of their problems. “Kerosene prices have doubled and electricity is irregular,” he says.

Govind Singh, a panchayat adhikari, says it is only this year that free electricity connections are being offered to Dalits and beneficiaries of the PM Awas Yojana, under Ujala.

Over at Saroj’s house, Adityanath eats three rotis and a little rice. Chillies are arranged when he asks for them. He finishes his dinner with a bowl of ras malai, arranged from a sweet shop nearby.

Around 10.30 pm, the CM goes to sleep at the Panchayat Bhawan. A meeting hall has been taken over by visitors and officers, while the panchayat secretary’s ‘niwas’, with an attached bathroom, has been turned into the CM’s bedroom.

Officials say the room is “sparse”, and all they arranged was a folding cot, bedding, a towel, a jug of water, a mosquito repellant and a cooler, borrowed from the pradhan’s house. They also fret that they could only arrange saffron towels and napkins, and not saffron bedding, as they had hoped.

Shiv Pratap says he is planning to display the items used by Adityanath during the visit, such as the glass and towels, as memorabilia, at the Panchayat Bhawan.

Looking on, a harried Shambhu Kumar, the DM, says he is not “in a state to talk”. “We have not slept for three nights.”

Realising Adityanath has retired for the night, the crowd starts drifting away. Many wonder at the import of what has transpired over the past two hours. “Iska kuchch hoga (Will anything come of this)?” says Rekha, looking drained. “They only took my application, but how will I follow it up?”

A young man shrugs. “Nothing will happen. These politicians only come and talk.”

***

It’s been a day and a half since Adityanath left, after flagging off a ‘School Chalo Abhiyan’ the morning after his stay. He boarded the chopper, that had been waiting in a clearing, for a “surprise visit” to Sultanpur district. A convoy of five SUVs ferried away officers and local BJP leaders soon after.

But the consequences of the April 23 night linger on. Shiv Pratap isn’t the only one sweating, and officials with creased foreheads go about setting up camps taking account of pending projects, making lists of new beneficiaries, and trying to solve problems of villagers who approach them.

The saffron handkerchief on his lap now, Shiv Pratap says he has spent “15 years” “ensuring the village is developed”, getting it a water tank, three primary schools, one middle school, a girl’s high school, a primary health centre and a veterinary hospital. The CM wasn’t too pleased with the village schools, he admits, but adds, “Have you ever heard of a village with an animal hospital?”

The people in the crowd before the CM, who accused him by name, were not from Kandhai-Mudhupur but “neighbouring villages”, Singh insists. “The BJP’s booth-level workers got them to impress the CM. That is how the voice of the good work done in Kandhai got drowned out.”

The Dalit outreach

In his speech in Karnataka on Thursday, PM Modi said BJP, once tagged as a “Bania-Brahmin party”, had done the most for backward communities. When it comes to Dalits, who are believed to have contributed to the BJP sweep of 2014, its target has been focused, including dining or staying at Dalit homes since 2015:

2015

April: Modi lays foundation of Dr Ambedkar International Centre in New Delhi

May: Committee set up under PM to celebrate 125th birth anniversary of Ambedkar

Oct: Modi lays foundation of Dr B R Ambedkar International Memorial in Mumbai

Nov: PM inaugurates Dr Ambedkar Memorial in London; participates in Parliament discussion to mark Constitution Day

2016

Jan: Modi addresses convocation of Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University at Lucknow, laments the death of Rohith Vemula; on the directions of PM, Republic Day sees a tableau on Ambedkar

March: PM lays foundation stone for Dr Ambedkar National Memorial in Delhi

April: PM visits Mhow, Ambedkar’s birthplace in MP

July: Ram Nath Kovind, a Dalit leader, is named President

2017

Dec: Modi inaugurates Dr Ambedkar International Centre in Delhi

2018

April: Government appeals against ‘dilution’ of SC/ST Act; files SLP against Allahabad HC decision on reservations in faculty recruitments; inaugurates Dr Ambedkar National Memorial in Delhi

April 14-May 5, 2018: Concerted Gram Swaraj Abhiyan, where BJP leaders to stay in villages with more than 60% Dalit population or at least a thousand Dalits. At the shortlisted “20,844” villages, BJP leaders to check implementation of seven flagship programmes of the Modi government — Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (LPG scheme); Saubhagya (electricity scheme); Ujala scheme (affordable LEDs); Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana (insurance scheme); Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (also an insurance scheme); and Mission Indradhanush (health scheme)