More than ever before, black people are telling their own stories on British stages. Plays such as Nine Night at the National – in which a Caribbean family prepares to bury their recently deceased matriarch – have gained rave reviews. Everyday depictions of black life are now celebrated. But what about extraordinary black stories?

For Rachael Young, whose show Nightclubbing comes to Camden People’s theatre next week before heading off on a tour of the UK, incorporating the extraordinary into the everyday became possible with the help of one thing: afrofuturism. A term coined in 1993 by cultural critic Mark Dery, today afrofuturism is defined as “a movement in literature, music, art etc, featuring futuristic or science fiction themes which incorporate elements of black history and culture”.

Keisha Thompson, whose show Man on the Moon used afrofuturism to explore themes of family and mental health, expands on the concept. “At its core, afrofuturism uses the black experience to create work that is otherworldly, cosmic and surreal. For me, it’s about creative freedom. Using political pain and channelling it. Taking the experience of being ‘othered’ and subverting it into something otherworldly. It’s about using the knowledge of our ancestors to battle the erasure that we experience on a daily basis.”

In Nightclubbing, Young (alongside musicians Mwen Rukandema and Leisha Thomas) bounces between telling two stories. One is the life of Grace Jones, whose groundbreaking 1981 album gives the show its title. The other is the imagined biography of the four black women who were turned away from the London nightclub Dstrkt in 2015. The incident gained widespread media attention and kickstarted a conversation about the racist door policies of many London venues. Rapper Stormzy even dissed the club on First Things First, the opening track on his debut album. For Young, the afrofuturist themes she works with today stemmed from thinking about these women, their lives and what they could represent.

“The show came from the club incident,” she says. “Knowing what it’s like to be a black person from Nottingham – where you’re basically invisible – it hit me because I was like: what is this nonsense? Then I started thinking about these women being dark-skinned. I was wondering about which women get to transcend these things, and I got to a place where I found Grace Jones. Growing up, Jones was always this person that was always breaking away from the norm and doing her own thing, and she has always managed to be authentic. She’s dark-skinned, androgynous, and as she’s always been ahead of her time, she can be – is – afrofuturist.”

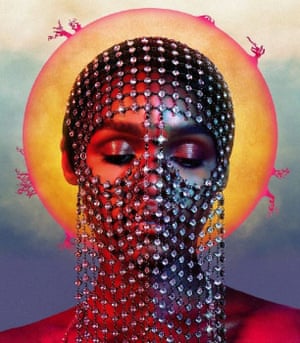

Afrofuturism has hit the mainstream more squarely than ever before. Science fiction writers such as Octavia Butler have gained newfound popularity as literary feminists strive to be more intersectional, while in music, artists such as Flying Lotus, Solange, The Comet Is Coming, Thundercat, Erykah Badu, Sun Ra and Janelle Monáe are all part of the movement. Then there’s Marvel’s smash-hit superhero movie Black Panther, which imagines an African country untouched by colonialism, and thriving, away from the world stage. Young calls the film “revolutionary. I saw these strong female characters, dark-skinned black women, as warriors and inventors, things that we don’t ever see.”

For poet and performer Vanessa Kisuule, who is currently working on a play with “elements of afrofuturism in it”, the appeal the genre has for black artists is obvious. “Afrofuturism frees our mind from the shackles of what a black artist ‘should’ speak on,” she says. “It is constantly assumed that black artists can only offer narratives that are ‘gritty’, urban and from our direct experience. I suppose the assumption is that we are so bogged down in our perpetual states of suffering that we haven’t the scope to think of much else. It is precisely because of this sociopolitical framework that black artists can have the capacity to dream up alternate worlds where we can, momentarily, transcend our current reality.”

For Young, using afrofuturism has been a way to allow her imagination to create a new normal. “I was asked the question recently: does your work try to rewrite history? No, it can’t. What is important is how you galvanise the energy from history to move forward with what you imagine that future to be like. And that’s why afrofuturism feels like such a simple but hopeful thing. To be able to read about all these inventors, to see black people in sci-fi, to dream. It’s this that gives me the impulse to say: OK, things can get better? It’s a long way off, but maybe we’re starting to take steps towards that happening.”