Her son needed help. It never came.

As overdose deaths climb, experts say time is now to offer better, quicker treatment

Her son needed help. It never came.

As overdose deaths climb, experts say time is now to offer better, quicker treatment

Poestenkill

Julie Roy had just dropped her son off at his grandparents when, not an hour later, she got the call.

"Julie, you need to come, it's really bad," the young man's grandmother said into the phone. "He's not breathing."

Next thing Roy knew, she was in her car, speeding across town with her four-ways on, her heart racing as she negotiated the winding roads and rolling hills from Poestenkill to Sand Lake, her mind desperate to quiet the clamor from her subconscious, which was shouting a truth she could not yet face.

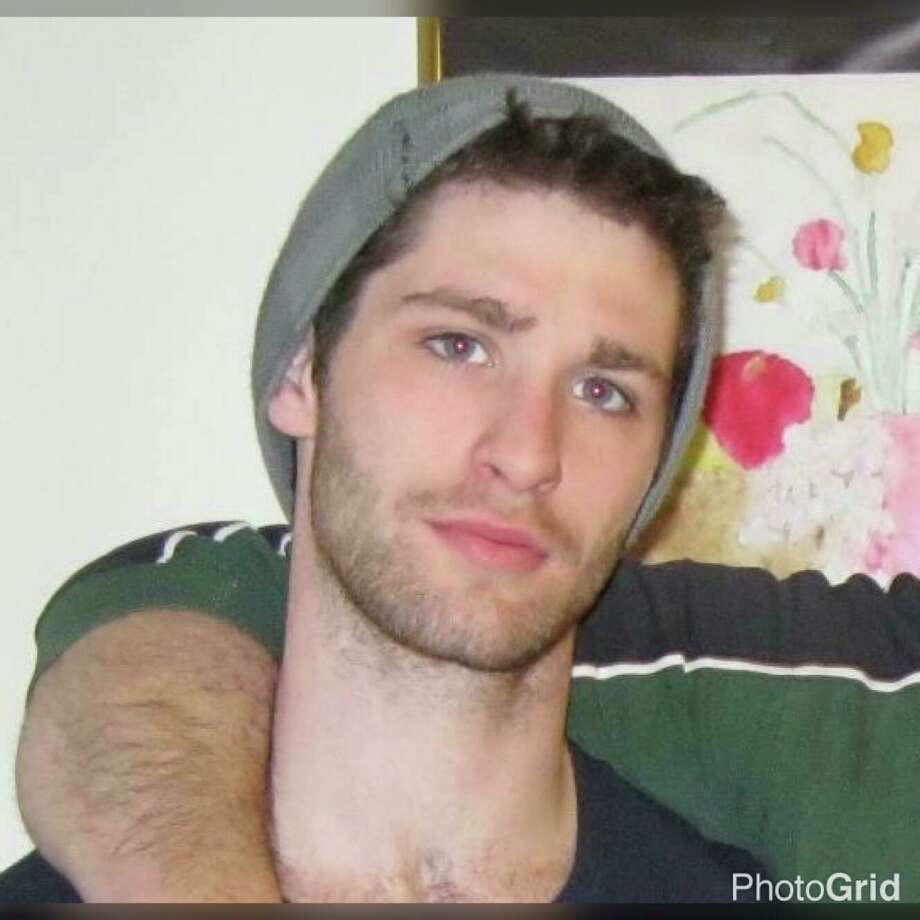

When she arrived, William John Timber was dead on the floor of his grandparents' bathroom, a needle in his arm. He was 26. An hour earlier, on that September day in 2015, he had hugged his mother goodbye and told her "I love you" — twice — she'll proudly recall more than two years later.

"I was lucky, in a way," she said.

Lucky, because so many others around her had gotten far less. Her son's friends, a cousin, young adults she remembered tromping through her house as kids — they were all dying from this stupid drug she once believed was just a city thing ("We don't have that here," she told her middle child, when he first told her Will was using heroin).

If Will ever worried he would be next, that overdose would claim him just like it claimed his friends, he didn't say so out loud.

"I still think he felt he was invincible because he always said, 'Don't worry, mom, I'm not gonna die. It's not gonna happen to me."

As deaths soar, barriers to treatment remain

Nearly 64,000 Americans died of a drug overdose in 2016, and roughly 40,000 of them overdosed on opioids — prescription painkillers, heroin, fentanyl and synthetic drugs. It's an epidemic that's not slowing down, and experts and advocates in the field say it's time to stop putting up roadblocks whenever someone tries to seek help for their addiction.

Just one in 10 Americans suffering from addiction receive treatment, according to a 2016 surgeon general's report.

It's no wonder, addiction experts say. Drug users encounter serious stigma when they come out of the shadows, far more than individuals with more "acceptable" addictions like alcoholism. And yet, research indicates that four out of every five new heroin users began by abusing prescription painkillers, which in many cases were legally prescribed by doctors who did not warn of their addictive qualities.

"There definitely remains a perception that folks who struggle with addiction — that it's somehow a character flaw and moral failing, and more about willpower than what it actually is, which is a disease that should be responded to like any other medical condition," said Melissa Weimer, medical director of St. Peter's Health Partners Addiction Recovery Center.

More providers are coming around to that perspective, she said, but addicts continue to encounter resistance when they seek help — from emergency rooms, treatment providers, insurance companies and doctors.

While work has been done in New York to increase treatment services, eliminate insurance barriers and expand access to withdrawal medication, much remains to be done if the state is serious about curbing its rising death toll, experts say.

People in the field say their top priority is plugging staff shortages, which are the result of low pay, odd hours and, if you ask them, "chronic underfunding" by the state and federal government. These shortages have caused delays for people seeking detox and rehab services, which wouldn't be as big a crisis, they say, if people had immediate access to withdrawal medicine.

Without it, and in the face of a long wait for help, many return to their drug of choice to prevent what feels like "the flu times 100" — body aches, sweating, nausea, diarrhea, plus a rapid pulse and extreme agitation, Weimer said.

"They'll feel like they're going to die but they won't actually die," she said.

Once someone does receive detox and rehab services, their insurance often won't cover a stay that's long enough for the individual and their counselor to address the underlying issues that caused someone to use in the first place.

"This is a chronic disease that you now have, that you need to manage as such, and it's not going to go away in a day," said Weimer.

As overdose deaths soar, people with opioid addiction continue to encounter barriers when they seek help and are increasingly desperate, according to Dr. Melissa Weimer, medical director of SPHP Addiction Recovery Center.

Media: Bethany Bump, Times UnionSlipping through the cracks in the system

More than two years after her son's death, Roy can count all the ways the world failed him.

There was the trooper who wouldn't call an ambulance after he attempted suicide and the doctors (about 20, by Roy's count) who said they couldn't prescribe medication for his withdrawal. There was the emergency room that turned him away for not being sick enough, the county employees who wouldn't make eye contact when he asked for housing to get off the streets, the prosecutors who agreed to lessen his charges if he gave up the names of other dealers, but who never once asked about his addiction.

There was the insurance plan that paid for rehab just long enough to get him clean but not a minute more. And, just four days before he locked himself in a bathroom and stuck a needle in his arm, a decision that proved fatal after three weeks drug-free, there was the judge who ignored a probation officer's recommendation. Will needed help for his addiction — intensive, inpatient, longterm help, the officer said — not more probation.

"I blame my son for making the choice he did to use drugs, but I don't blame him for being sick with addiction," Roy said. "Everybody told me, 'Tough love, do tough love, he'll hit rock bottom and get back up.' Not with opiate addiction. That's not how it works. He hit bottom but he had to crawl out. He needed help. But no one would give it."

Physicians like Weimer, who are trained in the science behind addiction and evidence-based methods to treat it, say the best way to stem the tide of opioid-related deaths is to make addiction medication available — widely, and without delay or red tape — to anyone who wants it.

Buprenorphine, commonly know by the brand name Suboxone, can alleviate an addict's suffering immediately and curb their cravings until they move up on a waiting list for more intensive treatment, such as detox and rehabilitation.

But the diagnosing and treatment of addiction is something that physicians, especially primary care doctors, have historically avoided. Such work was best left, in their view, to psychiatrists and addiction specialists. Even if they wanted to prescribe addiction medication, federal law requires providers undergo training and obtain a special license to prescribe it. It also imposes limits on the type and number of providers who can prescribe it and on how many prescriptions they can write.

Hoping to increase access in New York, the state Health Department began an effort last year to recruit more doctors, physician assistants and nurse practitioners to become buprenorphine prescribers by offering regional trainings and expanding the number of locations where the drug is available.

Yet, as drug use climbs to record highs in the U.S., more advocates are calling for the elimination of special licenses for prescribing rights and other restrictions that limit availability. Medicine to treat addiction, they say, should be handed out as freely as the painkillers that caused the dependence in the first place.

This single change could capture people at the moment they're about to fall back into a habit, and save their lives as more and more drugs on the black market are being laced with deadly doses of fentanyl, said Keith Brown, director of health and harm reduction at the Katal Center for Health, Equity and Justice.

"France, which had an overdose crisis in the '80s and '90s, basically just made buprenorphine available to everyone," he said. "You didn't have to jump through a thousand hoops, you didn't have to go get tested every day. They just made it available and their overdoses plummeted."

Dr. Melissa Weimer, right, consults with outreach specialist Megan Mulholland in the new ambulatory detox program at St. Peters Hospital Thursday Feb. 1, 2018 in Albany, NY.

(John Carl D'Annibale | Times Union)Within four years of the change, overdose deaths in France declined by 79 percent, according to one study that analyzed outcomes of the loosened restrictions.

A model to emulate

After turning away some 1,000 opiate addicts with withdrawal symptoms in a year, St. Peter's Health Partners realized last year it had to do more to save people from falling through the cracks.

By the end of September, it had opened a walk-in detox program at four locations in Albany and Rensselaer counties designed to get people dosed right away with buprenorphine until they could get more intensive help. More than 300 people have been served so far by the sites, which are on track to see more than 1,000 patients this year, Weimer said.

In addition, the hospital began keeping patients under observation for up to 72 hours if they sought help in the emergency room but were not sick enough to qualify for immediate detox services. On the average day, the hospital now provides detox services to about 18 people compared to 12 this time last year.

Local harm reduction advocates say it's a model other health systems should emulate.

The program is not just catching people at the start of their treatment, but is keeping them engaged after they are discharged by hooking patients up with ongoing services — medication assistance, outpatient counseling, even housing and social service supports — once they are stable.

It also connects them with Project Safe Point, a service of Catholic Charities that provides drug users with clean syringes and overdose-reversal drugs, just in case they do relapse and use drugs again, said Patrick Carrese, executive director of behavioral health at St. Peter's.

"Relapse is part and parcel of substance use disorder, and this is something society allows for people struggling with alcohol but not with other drugs," he said. "Our first rule needs to be, what do we have to do to keep you alive and keep you disease-free? After that, we can move on to the other stuff."

bbump@timesunion.com • 518-454-5387 • @bethanybump