Australia media after Sandpaper-gate (L) and Indian media in 2001.

Australia media after Sandpaper-gate (L) and Indian media in 2001.

At Junction Oval, Melbourne’s first cricket-only facility not obliged to share its green expanse with Aussie rules footy, there’s a value board with three distinct headers in bold capital in the following order: RUTHLESS, HONEST and UNITED. Below RUTHLESS are a couple of lines between which a lot can be read.

– Control the opposition to make it uncomfortable.

– Do whatever the team needs to prevail.

The watermark to the poster is from one of Victoria’s finest seasons — 1990-91 when the state side won the Sheffield Shield. These guiding principles were pinned to the wall much later when the amoebic Oval — famous for being the field where Shane Warne learnt his trade — was revamped to international-standards. This 1990-91 season was when the Victorian side had in its ranks Darren Lehmann and James Sutherland.

Cut to 2018, Lehmann was the Aussie coach and Sutherland the CEO of Cricket Australia. Under their watch three blokes wearing the Baggy Green — Steve Smith, his deputy David Warner and Cameron Bancroft —messed up almightily by being caught on camera using a sandpaper on the ball. In the wake of the scandal, Lehmann’s on-field RUTHLESSNESS, and Sutherland’s away from from it, came under the scanner. The duo’s response to the scandal, though, has shown that those values — a hallmark of all Australian teams — will be revised to accommodate a new philosophy.

An independent review of how Australia will play its cricket in the future, is underway. As a start, the country’s sporting leadership proceeded to ban captain and vice captain for a year. Punishment was the logical conclusion of the crime. Opinion varies on whether the punishment was far too much or way too little. Positions waver between whether the offenders panicked and blurted out the confessions as the video had made their positions untenable or if Smith & Co could’ve decided to lie low and let matters fade out, like so many before them. But once the genie was out of the bottle, no one in Australia was going to try shove it back in.

When confronted, Australians don’t bring up Faf du Plessis, who in the past had been pulled up for ball-tampering. And they don’t call for ball changing rules to be radically reconsidered, when cornered. Even Kookaburra representative Shannon Gill says he’d want the sanctity of the ball to be maintained for the 80 prescribed overs, despite the fact that a cricket ball is meant to deteriorate anyway.

A week spent across three sports-mad cities Brisbane, the Gold Coast and Melbourne, and you realise this is not a country about to launch into defensive whataboutery.

Nor are Australians living in denial.

***

Former Australia quick Michael Kasprowicz reckons as deeply concerning as the turn of events was, it brought out Australia’s love of cricket. “It showed us it’s our favourite sport and hence important to rebuild. It was the start of football season (soccer and Aussie rules footy), and those guys were a little jealous that everyone was talking about cricket. It was terrible but people still care for the sport,” he says in Brisbane, speaking both as director on board of Cricket Australia, and a former player.

Steve Smith admitted to ball-tampering. (AP Photo)

Steve Smith admitted to ball-tampering. (AP Photo)

At the Gold Coast, every speaker at the Commonwealth House which brought together government, academia, sporting and business perspectives on the sidelines of the Games, took it upon themselves to start with a contrite cricketing preamble — this when cricket wasn’t even on the CWG programme. CEO Sports Commission, Kate Palmer, echoed what the political top brass had been saying. “It was an error in judgement. But like the leaders have said ‘Brand Australia was affected.’ Because what came through was that when the going gets tough, we’ll cheat. That’s not done,” she said. “It’s not something we stand for as a country. It’s damaged our reputation,” she added.

Many outside of the country believe that starting with the Australian PM downwards, the reactions were far too stern in telling off the trio and the punishments disproportionate to the crime. But more or less, PM Turnbull was merely the brightest shade of raging crimson, reacting to the scandal.

***

Paul Faulkner is a regular at the MCG on Boxing Day Test, and also for all of Richmond club’s Footy games over the autumn-winter. His interest in the Indian sports market is as the Melbourne AFL club’s India engagement executive. “The tipping point,” he recalls from days of the scandal, “was that they lied it wasn’t sandpaper, but just some tape. The lies did it for me.”

He would explain the frenzied fury, saying, “As an Australian consumer, it is painful as a nation to be embroiled in this. We always hope our sport is clean, and we do things the right way. It’s bad that it happened to our captain/vice captain, but it was immediately dealt with, because public demanded action.”

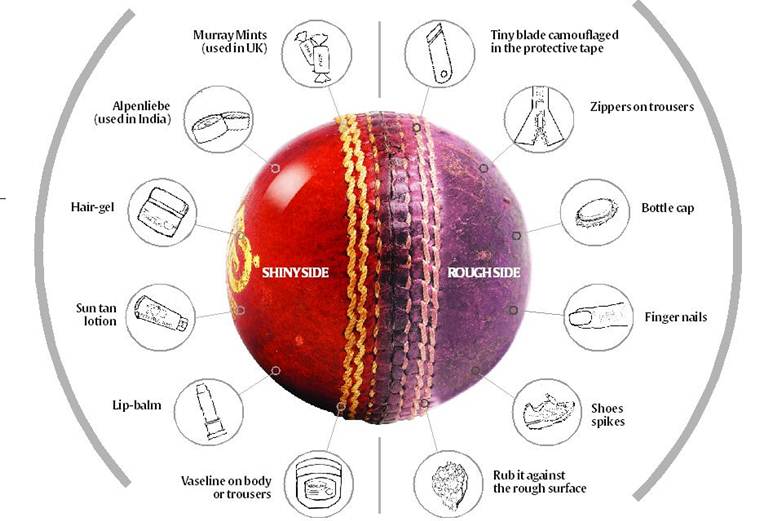

How ball tampering works.

How ball tampering works.

He recalls a scandal where his other loved sport, faced heat at the start of the last season. Footy players routinely go for 147 kg on the bench-press and put in 200 squats in a single session, and can run up to 18km in one game. Recovery is all-important, and some backroom scientists had kept themselves busy in the off-season. “One of the clubs was experimenting with vitamin supplements for maxing performance. They were walking a fine line, but it was found to be illegal within the existing framework of rules. There was swift punishment from Australian Anti-Doping, and it was made very clear that players are not guinea pigs,” he says. Both rules and spirit guided that decision.

As precedents in cricket go, the trio’s punishment sets the template for dealing with future tampering indiscretions. There’s no dearth of critics pouring scorn and accusing Australia of taking a non-existent moral high ground, given its history of past transgressions and sledging and some painful sermonising. But whether the world likes it or not, a moral high ground has been plonked in cricket’s midst by a country that showed it won’t tolerate further cheating. “Whether cricket or football (AFL), punishment should be firm. It’s probably harsh, but needed,” Faulkner says.

***

It doesn’t get harsher than wishing someone dead and buried where his decomposing corpse can fertilise cabbage plants. It can, of course, be passed off as humorous when the intended audience is India’s cricket fanatics, frothing at the mouth because Sachin Tendulkar has been called out for ball tampering. In fact, everything was kosher that summer of 2001 as a nation parried back this sacrilege. Burning with righteous fury and avenging centuries of colonial humiliation in the South African studio was Navjot Singh Sidhu. He channelled no one less than Mark Twain when throwing this dart at Mike Denness: “I don’t think Mr Denness should be on the top of the ground. He should be down there inspiring cabbages.”

During the second Test against South Africa at Port Elizabeth, TV cameras showed Tendulkar’s fingers going over the seam of the ball and Mike Denness pulled out the rulebook. The batsman claimed he was cleaning the seam of the ball when called out, but because he hadn’t notified umpires he was doing it, it fell under the regulations for altering condition of the ball. The infringement would’ve cost him a game ban and match fees.

Coming from Mike Denness —who came from the UK — the punishment was one game and match fees too many for a man they called God. India submerged the bottle with the genie deep someplace in the ocean.

The narrative was obfuscated ridiculously by Indians to highlight both how the country was being victimised and how it was strong enough to bully even the ICC into submission. After the Indian government waded in and Jagmohan Dalmiya did his sabre rattling, Tendulkar ended up whisked away from the potential blemish. The villain of the piece was firmly Mike Denness.

Former player Ravi Shastri would turn bellicose, scolding Denness at a press meet, saying, “If Mike Denness cannot answer questions, why is he here? We know what he looks like.” He’d roar, “When you heard, an Indian legend was accused of cheating — it made you wince, made your hair stand up.”

He’d threaten: “ICC need to act sensibly or I fear there’ll be something drastic.” He’d plead innocent: “There’s no precedent. Denness has taken half the side out! It’s never happened before!”

And he’d insult: “Denness has a good chance to show character again, by dropping himself as match referee. The Indian Ocean is close by — Denness should go take a dip.” [As England captain, Mike Denness had once dropped himself from the playing XI.]

Denness wasn’t re-appointed as match referee from the next year and the ICC Disputes Resolution Committee was cancelled after he underwent heart surgery. Tony Greig, speaking from UK, would declare: “Guilty as guilty can be of manipulating the ball, as far as I’m concerned, so Denness is justified. I cannot believe that anyone who sees that footage could possibly think of defending him.”

Cameron Bancroft attempted to tamper with the ball by using sand paper. (Source: Reuters)

Cameron Bancroft attempted to tamper with the ball by using sand paper. (Source: Reuters)

India though had invoked everything from racism to indignation at assuming that Tendulkar could have long-enough nails, directing the choicest disdain at Denness. Smaller punishments, followed by some clucking, has been the norm in ball tampering whether it was Rahul Dravid applying lozenge in Zimbabwe, Shahid Afridi biting the ball, Mike Atherton’s pocket full of dirt, Marcus Trescothicks’ Murray mints, Faf du Plessis’ zipper + mints, Stuart Broad’s stamping, Jimmy Anderson’s handling or Pat Symcox’s icky cocktail of sweat-and-spit. In some instances, commentators simply cackled away at the sight of brazen pawing of the ball or umpires changed balls prematurely, letting off teams.

Sachin Tendulkar got an entire country shielding him as charges never came up for debate with BCCI pressuring ICC eventually. In Australia, three men invited derision and were banished for a year, for confessing.

***

Punishment brings closure in sport, as in life. It reduces resentment and snips at deep-nursed regrets. It doesn’t leave you bumbling through a troubling argument that “Maa ki” isn’t as bad as “monkey.”

It saves you from revisiting match referee Mike Procter, who was ghosted by the fraternity for calling out a nation’s popular sports figure for indecent chirping. It doesn’t embolden wrestlers from a country to bite opponents’ ears on way to a medal. And it doesn’t leave you aghast at the sight of your national Olympic committee attempting to sneak in a wrestler into an Olympic draw, days after he was caught doping.

Punishment might seem unreal to some, while you march an athlete from your own country to the docks and get them to face the music, knowing a few matches will be lost in the bargain. But national flags have been sport’s oldest cotton-wool, and it’s not uncommon for countries to wrap their sinners in the protective shield of the flag. Australia this time, didn’t.

Cameron Bancroft tried to hide the piece of tape in his underwear.

Cameron Bancroft tried to hide the piece of tape in his underwear.

In Cape Town, two men fronted the admissions of guilt. Across the ocean, the whole of Australia was owning up and facing the ghosts. Adam Gilchrist sat in the studio for the Australian F1 Grand Prix with four TV presenters that Sunday, not quite threadbaring Seb Vettel’s podium. Disco music played out in the background of the news-current affairs talk show ‘Sunday Project’ at Albert Park, but the five took turns to hit the blues notes as a country tried to come to terms with these confessions of cheating.

“We’re fixing our society and cricket is part of the fabric of our nation, and it means so much. But now we’re the laughing stock of the sporting world,” Gilchrist would say, adding how his stomach churned watching the replays and how he saw no way how Smith could be captain, going forward.

There was talk of facing up to the bad mistake, and a consensus that this was far worse than the under-arm bowling which, though not sporting, had been legal.

“This is black and white in rules. There’s no defence because they came and said it themselves,” Gilchrist would say, adding that the only small speck of positivity was that the Australians had accepted their mistake, and the country wasn’t “sitting here looking at visuals, frames and speculating on vision.”

PM Turnbull who had said he was shocked and bitterly disappointed would rage on. “Cricketers are our role models. How can our team be engaged in cheating like this – it beggars belief!” It’s the most “passionate” the Australians had seen him “about anything,” the five in the studio would quip.

“Out for one game, and a match fee and not much more than that?” the lady presenter Lisa Wilkinson would wonder, showing how the Australians saw this as a far more serious transgression than the ICC.

While Sutherland started his fire-fighting with: “This morning I have every reason to not be proud,” former captain Michael Clarke pulled no punches, when declaiming the team despite calling “Steve Smith a lovely, lovely guy.”

“It was blatant cheating, premeditated and disgraceful, not accepted by anyone. We have the best bowling attack, we don’t need to cheat to beat anyone,” he would say. While the sanctions under CA’s Code of Conduct 2.3.5 reflected the gravity and the damage caused, Cricket Australia had set about recalibrating their behaviour compass even beyond.

A stark contrast to what India in 2001 had been.

“Athletes are living their dreams representing the country at international level and obsessed with winning,” explained Kasprowicz who’s moved from player to administrator. “It’s not in the job description when they get selected–this moral code that they need to follow, though it should be. These blokes are often good people. But the hardest thing for them is not batting – bowling skills or all the travel; it’s perception. Every moment someone is judging you.” The world tires of carefully constructed “images” too, but modern sport rightfully demands that athletes —behave.

Cameron Bancroft, of course, should not have needed an etiquette manual on how he shouldn’t shove a sandpaper down his pants, neither should Smith or Warner have needed telling twice that they were on the path to doom — and looking stupid every step of the way. But the only logical action in the aftermath, was punishment. Not just for being caught, but for erring.