Continuing where we left off last week on the subject of an Eastern Switzerland, it is clear that dreaming is free and there is no charge or cess levied on it. First Maharaja Hari Singh, his PM Ram Chandra Kak and then later Sheikh Abdullah dreamt of a free and independent Kashmir wedged between the Great Powers.

For Jawaharlal Nehru it was India’s crown jewel, a show window for his secular credentials, a Muslim majority Princely state not part of theological Pakistan, but instead opting for India. It suited his narrative. The remarkable part of this accession is that Nehru stuck to his guns despite being outmanned many times over his controversial decision. Even when the adrenaline rush passed, he remained steadfast to the cause of Kashmir for he knew what it represented in terms of optics. History will tell you that despite pushbacks being asked for by many of the involved players, he didn’t budge. That he probably gave too much to Abdullah and then later had to cauterise is another matter. Even then, he accepted Director Intelligence Bureau B N Mullick’s contention that Sheikh must be arrested in the Kashmir Conspiracy case. The nation came first. Every story has a back story and in Sheikh Abdullah’s case, it was complex and complicated. To get a peep into his mindset, I am repeating a hitherto unknown story.

Ihsan Abdel Quddous, a member of the Egyptian press delegation (a famed essayist, columnist and writer) which visited India, sat in an aircraft during his trip within the country only to find that his neighbour was Sheikh Abdullah, then prime minister of Kashmir.

Quddous, writing in Rosa El Youssef, said that he asked Sheikh Abdullah why he had chosen to accede to India? While endeavouring that Kashmir might be made an Asian Switzerland, Sheikh during the conversation recognized the impossibility of that endeavour, that designs against his country were too strong to be resisted, and that as one is given by him to understand, it will ultimately have to join either Hindustan or Pakistan.

Quddous wrote: “This would leave one in doubt as to Sheikh Abdullah’s preference that his country should join India and not commit suicide through accession to Pakistan. Throughout the state of his struggle against the British and the Maharaja, the only support he received was from the Congress party, Gandhi and Nehru. The late Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the creator of Pakistan, had on the contrary considered him as an extreme leader who is more deserving of imprisonment rather than support”.

He went on to write : “It was only natural that Sheikh Abdullah having become the prime minister at a time when the Maharaja was still the Head of the state, should mitigate the aggressiveness of his attack against the Maharaja; but Sheikh Abdullah has contrary to expectations, become more aggressive”.

That sums up Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah, Sher-e-Kashmir in the immediate aftermath of accession to the Indian Union. Tough, unrelenting, uncompromising and obdurate, he played hardball from the beginning with the Government of India, in the main the States ministry under Sardar Patel’s helmsmanship. And this was primarily driven by the fact that Patel was covertly supportive of the Maharaja. Realising that Pandit Nehru had a soft corner for him, Abdullah displayed his antipathy for Maharaja Hari Singh in no uncertain terms.

In fact, as far back as September 27, 1947, Panditji in a letter to Sardar stated: “There has to be peace between Maharaja and the National Conference and they should cooperate together to meet the situation”. Panditji went on to suggest that while this was not an easy task : “It can be done chiefly because Abdullah is very anxious to keep out of Pakistan and relies upon us a great deal for advice….The main thing is that the Maharaja should try and gain the goodwill and cooperation of Abdullah….. I don’t think it is possible for the Maharaja to function for long if no major section of the population supports him”.

In many ways, this story revolves around these four protagonists – Nehru, Patel, Abdullah and Hari Singh. The inherent conflict between the four – the pulls and pushes – are what this treatise attempts to unravel. And Nehru, being a Kashmiri himself, always stood like a rock as far as Kashmir was concerned. In another letter to Hari Singh on December 1, 1947, he wrote: “From our point of view, that is India’s, I need not go into the reasons for this as they are obvious, quite apart from personal desires in the matter which are strong enough”. The bond between Nehru and Abdullah was strong enough to see the latter attend his daughter Indira’s wedding to Feroze in 1942 and rush back from Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) to attend Panditji’s funeral in 1964. Or for Nehru to rush to Kashmir to assist in Sheikh’s trial in 1946 and actually be arrested by the Maharaja’s government.

Hari Singh and the Balraj Madhok-spawned Praja Parishad were constantly targeted in Sheikh’s crosshairs and in the end, the Hindu Jammu and Muslim Kashmir chasm was too much to bridge for him. This holds good today as well and is more pronounced now that Hindu Jammu is under BJP rule and Muslim Kashmir Valley is under PDP, two Right wing formations principally opposed to one another forging an Agenda for Alliance is the stark contradiction that has laid bare the maelstrom in the Valley.

But let us psycho-analyse the genesis of the Asian Switzerland.

SHEIKH MOHAMMED ABDULLAH IN DELHI, MAY 17, 1949

“For sometime past, I have noticed some controversy going on in the press about Kashmir’s reported desire to remain independent. Who does not know that Kashmir is passing through a very critical stage and mishandling of grave issues might cause her irreparable damage?

“The National Conference has always, and during the past decade particularly, given positive proof of its alliances outside Kashmir and has not vociferously expressed her choice between the two Dominions, but has, while expressing the will of the people, sacrificed and struggled against heavy odds for linking up the four million people of Kashmir with their 300 million brethren in India.

“This alliance and link up is not artificial, nor based on any arbitrary consideration, or sentimental factors. It is the community of ideologies and the goal of having a secular democracy established in our country, fighting with grim resolve exploitation of man by man, that constitutes the cornerstone of our friendship and alliance with the people of India.

“We have fought times out of number the pernicious two nation theory which sets man against brother man, divides people into hostile camps and warring elements and thereby weakens them and perpetuates exploitation. This consciousness of the danger and steadfast adherence to our ideal always urged us to fight the Muslim League ideology, and to stand against Pakistan, which represents a theocratic state.

“Even when India and Pakistan agreed to divide the country on the basis of Hindu and Muslim majority areas, Kashmir stood fast by the ideal of a secular democracy, and not withstanding the fact that it is a Muslim majority area, it made a choice for India. Again, at the time of the Pakistan engineered attack on Kashmir, when the administration there had completely collapsed and when no power on Earth could have stopped Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan, if she so desired, the National Conference with all her organizational might rose to a man, resisted attack and refused to go to Pakistan and not only saved Kashmir from physical extermination and ideological suicide, but also vindicated the great ideal for which Mahatma Gandhi stood for.”

Sheikh Abdullah’s towering persona may have decided which way the pendulum swung in those fateful days, before the division of India vis-à-vis Kashmir’s accession to India, but the aforementioned statement sums up the ideals that he stood for. While many have doubted his nationalism in later years which led to his incarceration, at that particular point in time, his resolve to side with India could never be questioned.

In fact, talking in the capital (New Delhi), Abdullah hinted at forces which were even those early days of Kashmir’s long and troubled history out to destabilize the ‘cause’. Abdullah categorically asserted that the people of Kashmir will have to fight not only Muslims communalism, but Hindu communalism, not only in Pakistan but in India too. He said, “We must, with determination, fight all such elements, wherever they are. It is they who create difficulties in the way of the people of Kashmir”.

Therein lays the rub for the people of Kashmir. Abdullah, in his rhetoric, probably saw the future of Kashmir as far back as 1949. Slamming his detractors, he junked the independence theory saying, “It is absurd to say that Kashmir still thinks of any other alternative, so far as the accession is concerned. What we want is peace and prosperity for our people. Independence may be and is a charming idea. But as I have said before, is it practical too?

“Has it got the necessary sanctions and guarantees, and can a small country like Kashmir, with its limited resources, maintain it. Or all the countries concerned in a proper political temper, at the present moment, to give their willing and sincere assent to it or, by only after a formal declaration of independence, shall we not be making Kashmir a victim of some unscrupulous and powerful country. That will be a gruesome betrayal of the cause we have stood for, for all these years. Therefore, these and similar other considerations make the alternative of independence, not only theoretical and academic, but also meaningless.” Some analysts argue that Abdullah may have tried to float a trial balloon through this statement to gauge the sentiment in the capital for an independent Kashmir. But this is a subject that will be taken up later in this book.

Successive regimes in Pakistan have tried their level best to ‘free’ Kashmir in different ways, but without success. Till a low intensity war with the nomenclature of ‘Islamic jehad’ institutionalized with funding and arms from across the border has managed to subvert the system over the last seventeen years. This involved ethnic cleansing and stampeding the minority Hindu population based in the Valley. But that is not the objective of this book. That is a subject on which several tomes have already been written.

However, what bears recounting is the fact that while Pakistan tried a series of desperate measures practically from day one, the most notable came in January 1971 which somehow or the other has got buried in the dust bowl of history. Only fourteen miles from Srinagar, an Al Fateh headquarters was discovered in Barson. As many as 227 members were arrested including their leader Ghulam Rasool Zaheer. Interestingly, this was a double storied HQ with safe surroundings, observation posts and easy escape routes defended by a 900 feet long and 25 feet deep trench in front. The police later claimed that the mastermind behind this was Zafar Iqbal Rathore, first secretary Pakistan High Commission. Incidentally, earlier he was SP – Intelligence, Rawalpindi.

While many discounted the story, only days later, on January 30, in arguably the most successful terror strike of its time in India, Al Fateh claimed responsibility for the hijacking of an Indian airlines aircraft. It took off from Srinagar and was diverted to Lahore, where symbolically the plane was burnt, but the passengers were released unhurt.

The Indian government’s real problems began when Pakistan realized that it was wiser to use the time honoured tactic of – death by a thousand cuts – where guerrillas fight a large conventional force using ambushes, assassinations, attacks on supply convoys etc. Brigadier Mohd. Yousaf, head of the ISI’s Afghan Bureau in his book Bear Trap writes about the use of the Afghan model funded by proceeds from the Golden Crescent and religious institutions to fight this guerrilla war. This is when the ISI created ‘Markaz dawat ul Arshad’ – liberate the land from kafirs – stratagem was unveiled for Kashmir.

The genesis of the accession of Kashmir and the idea of an independent Kashmir are what this treatise will attempt to lay threadbare with the help of hitherto unpublished documents and some published letters between the dramatis personae of the time. Like J & K there was another vexed state - Junagadh - where a referendum actually took place on whether the people should opt for India or Pakistan.

Supported by India, on October 24, 1947, volunteers rose up against the Nawab and captured the tiny state. On February 20, 1948, India conducted a plebiscite in which a little more than 2 lakh people voted. India won the vote, with a grand total of 91 people opting for Pakistan. It wasn’t over though. In many ways, this suited Pakistan. Junagadh was a tiny principality. The real prize was Kashmir. Would the referendum in Junagadh set a precedent for Kashmir – a mirror image of the Gujarati state, with a Hindu king and a Muslim-majority populace? On September 22, 1947, Pakistan’s prime minister asked a Mountbatten aide, “Why, if it was suggested that a referendum should be held in Junagadh one should not be held in Kashmir?”

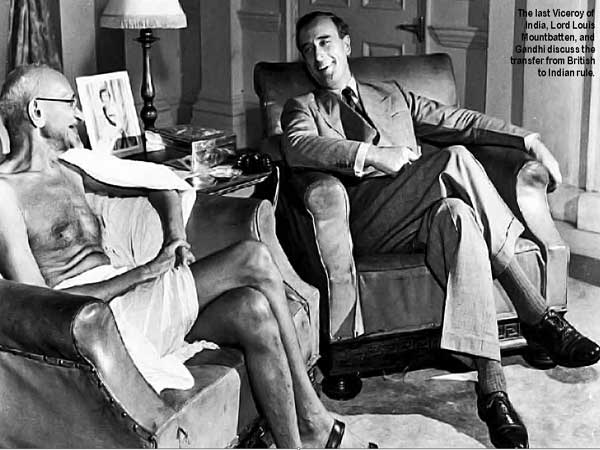

In confidential aide memoire written by the then governor general of India, Lord Mountbatten on Junagadh dated February 25, 1948, some other misplaced notions and misunderstandings are dissipated. The question mark over Kashmir’s accession to India, which remains shrouded in controversy, can have no better defence than the one provided by Mountbatten here.

Reflecting on three main misunderstandings, Mountbatten gives a lucid account of what was right and what was wrong in terms of perception. These bear repetition :

that the Government of India took possession of Junagadh state by force, after its legal accession to Pakistan, and has largely vitiated its case in Kashmir by its action on Junagadh;

that the Government of India brought pressure to bear, at various times, on the Maharaja and the government of Kashmir in order to induce the state to accede to the Dominion of India; and

that the Government of India planned the dispatch of Indian forces to Kashmir sometime in advance of the date, these forces were sent.

The governor general states in the aide memoire that none of the statements is true: “I shall deal with them one by one from my personal knowledge, for I was present at all the meetings at which the various decisions were taken”.

The aide memoire which is presented now goes onto clarify several of the perceptions and myths which continue to cloud people’s judgement even to this day, nearly sixty years later.

MOUNTBATTEN’S AIDE MEMOIRE DATED FEBRUARY 25, 1948

Junagadh

The right of states to accede to either dominion

On July 25, 1947, I addressed, in my capacity as Crown Representative, a special full meeting of the Chamber of Princes. At this I informed the rulers and their representatives of the policies of the future governments of both India and Pakistan, which I had worked out with them, with regard to the formation of Instruments of Accession and Standstill Agreements by and with states.

I made it clear that all the states were theoretically free to link their future with whichever Dominion they wished or even to remain independent. I pointed out that separate State Department had been set up for each future Dominion Government. But I added the following words – When I say that they are free to link up with either of the dominions, may I point out that that there are certain geographical compulsions which cannot be evaded.

I made my views on the geographical compulsions clearer whilst I was answering questions at the end of the conference. I hoped that both the future governments of India and Pakistan would take note of an agreement with the principle I had enunciated.

In the case of the Government of India, this was openly done, and the principle was scrupulously followed. A large state which had obvious geographically compulsions to accede to Pakistan – Kalat – approached the Government of India for political relationships, but was refused; and unofficial overtures from Bhawalpur was similarly discouraged.

I also gained the impression from various conversations which I had with the leaders of the future Pakistan that they too intended to recognize this principle and not to enter into a ‘competition’ with India in obtaining accessions. Indeed Sardar Nishtar, the states minister for the future Pakistan government, minuted his agreement with the principle on the file, and it was in pursuance of this agreed policy that the offer of Kalat was turned down. The leaders of India naturally assumed that this principle would be scrupulously adhered to by Pakistan as by tem.

Of the 300 odd states in Kathiawar, Junagadh was the premier and the largest, with a population of 700,000 (82 per cent Hindu), an area of about 3500 sq miles, and a geographical position that makes it an essential factor in the unity of Kathiawar. It has a seaboard and ports, which are not open regularly during the monsoon. It is inextricably mixed up with Kathiawar states which had acceded to the Dominion of India. In the middle of Junagadh were pockets of territory belonging to other states, similarly pockets of Junagadh territory were to be found in the middle of surrounding states. The railway and posts and telegraph services of Junagadh were an integral part of the Indian system. The railway police, telegraph and telephones were administered by the Dominion of India, and under Section 7 of the Indian Independence Act continued to be the concern of Dominion until renounced by the state.

I trust that these facts will support the theory that the accession of Junagadh to Pakistan would be in violation of the basic principles of accession which both agreed, at least tacitly, between future ministries of India and Pakistan. Junagadh is, furthermore, linguistically, culturally, economically and strategically linked with the territories surrounding it and with India.

At the conference held on July 25, 1947, the Junagadh representative Nabi Baksh asked me a series of questions. But I did not detect from these any intention on his part that his state should accede to Pakistan. Indeed he told me, when I met him privately afterwards, that he had every intention to accede to India. Furthermore, he gave the same impression to Jamsaheb of Nawanagar and Sardar Patel.

Both before and after July 26, authorities on behalf of the Junagadh government, including the Nawab himself, made repeated declarations that Junagadh stood for the unity and solidarity of Kathiawar and that the state would make common cause with other Kathiawar states to maintain peace and security in that area. The first of the declarations was contained in a press statement as early as April 11, 1947, in which the need for the solidarity of Kathiawar was emphasized and the formation of a self contained group of Kathiawar states was favoured.

The failure of Junagadh to accede to India by August15 caused some surprise to my government, but no special action was taken to secure Junagadh’s accession. My government put no pressure on Junagadh, for, although, it was certainly their intention to enter into negotiations, they were careful to avoid any action likely to give cause for any accusation of coercion being levelled against them.

As soon as the possibility of Junagadh acceding to Pakistan became clear, the Government of India pointed out to Pakistan the patent impropriety and injustice of accepting Junagadh’s accession and made two formal efforts to obtain a declaration of the intention of the Pakistan government in regard to this matter, but there was no response.

Accession of Junagadh to Pakistan

The news of Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan, in mid September 1947, came as a very considerable shock to the Government of India. It was felt that it might have a serious effect on the whole of the government’s accession policy. For instance the Jamsaheb of Jawanagar made it clear to me personally that unless the Government of India had the will and the capacity to prevent Junagadh from going over to Pakistan, the confidence of the princes as a whole and the value of their own Instruments of Accession would be shattered; and the position of the Kathiawar states would be particularly seriously jeopardized.

The government of India, besides making further representations to Pakistan that the issue should be decided according to the wishes of the people of the state sent the secretary of the States Ministry to Junagadh with a personal message to the Nawab. He was refused permission to see the Nawab, but the Diwan admitted to him, at that early stage, that he was in favour of a referendum.

I will not try and analyse Pakistan’s purpose in accepting the accession of Junagadh. But I would like to quote the opinion which Lord Ismay put forward to me – that the project was so fantastic from the military point of view, and such a liability politically and economically to Pakistan, that it had the appearance of a trap: and that the Pakistan government was deliberately trying to tease the Government of India into taking precipitous and aggressive action.

Lord Ismay was convinced that this was the real motive underlying Pakistan’s action, as a result of talks which he had with Mr Jinnah. It appeared to be primarily a propagandist move and part of a wider campaign in which Pakistan was posing as the innocent small nation – the victim of aggressive designs of its large bullying neighbour. It was also considered, as subsequent events confirmed, a convenient bargaining counter for Pakistan vis a vis Kashmir.

During the two months which followed the accession of Junagadh to Pakistan, the Government of India made no attempt to challenge the accession; although they remained of the opinion that, in the circumstances in which it was made, they could not themselves recognize the accession. They reiterated their wish to find a solution of the problem by friendly discussions with representatives of Pakistan and Junagadh and repeated their policy that any decisions involving the fate of large numbers of people should depend on the wishes of those people.

Babariawad and Mangrol

Among the large number of states in Kathiawar which had acceded to India were Babariawad and Mangrol. Mangrol was a separate entity, which had declared its independence on the lapse of paramountcy. Similarly the mulgarasis of Babariawad declared their independence.

The legal right of Babariawad and Mangrol to accede on their own was questioned by the government of Pakistan. In view of this, the Government of India refrained for long from ordering Indian armed forces to take over from the Junagadh armed forces which had taken possession of these parts of Indian territory. The prime minister of Pakistan undertook, but failed, to induce Junagadh to withdraw these forces. On November 1, Indian troops entered these two states under a flag of truce without a shot being fired in order to give them that protection, which their signatures of the Instruments of Accession demanded, against the increasingly oppressive action of the Junagadh authorities.

On September 25, the provisional government of Junagadh was formed. It moved from place to place and ejected the forces and officials of Junagadh. But the Indian government did not recognize the provisional government. The real cause of the breakdown of the state’s administration was undoubtedly the fact that the Nawab emptied the treasury when, soon after accession to Pakistan, he fled to Karachi.

On November 9, a telegram was sent by Pandit Nehru to Liaquat Ali Khan. This sets out so clearly the reasons for the entry, the following day of Indian troops into Junagadh.

The Telegram

Our regional commissioner at Rajkot was approached yesterday by Harvey Jones, senior member of the Junagadh State Forces, with a letter from the Junagadh Diwan Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, appealing to the Government of India to take over the Junagadh administration. This request was made in order to save the state from complete administrative breakdown and pending an honourable settlement of the several issues involved in the Junagadh accession.

It was subsequently transpired that before sending his letter of November 8, the Diwan of Junagadh had obtained the consent of his Ruler Sir Mahabatkhan Rasulkhanji, who had fled to Karachi. The new administrator naturally brought in some Indian troops. As they entered Junagadh, they were met and led in by Jarvey Jones himself.

Junagadh Referendum

At the time of the preparation of this paper, a referendum has just been held in Junagadh, under a senior judicial officer, who is neither a Hindu nor a Muslim. It resulted in an overwhelming vote in favour of India.

Final Opinion

When I saw Mr Jinnah at Lahore on November 1, he gave me his view that there was no sense in having Junagadh in the Dominion of Pakistan, and that he had been most averse to accepting this accession. He had in fact demurred for along time, till he had finally given way to the insistent appeals of the Nawab and his Diwan.

@sandeep_bamzai