In it together: CPI workers in an agitation against the Maharashtra government, 2012. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

In it together: CPI workers in an agitation against the Maharashtra government, 2012. (Express photo by Prashant Nadkar)

In a span of 17 years, M Sukumaran, the Malayalam writer, wrote about 70 stories. At the peak of his writing career, when he was just 39, he retreated into silence. That was in 1982. Since then, until his death last month, it was his silence that marked his presence. The two novellas he wrote in the long interval between his self-imposed silence and death were prescient in marking the trajectory of the communist movement in Kerala, but they were aberrations. Two generations of readers celebrated the small corpus of stories, distinguished for a rare political thrust and narrative skill, and mourned the demise of the author.

Sukumaran was a product of the 1960s and ’70s, a period of great political and cultural ferment. The post-war social consensus in Western Europe had broken down and Soviet communism was under challenge from a new radical Left. Mao’s China was increasingly becoming influential among Left radicals. In India, the gains of the Independence movement and the Nehru years were being questioned. The debates within the Indian communist movement had led to two major splits, resulting in the formation of the CPM in 1964 and the CPI-ML, following the Naxalbari uprising, in 1967. Indira Gandhi’s left-of-centre policies in the late 1960s gave way to a political and economic crisis in the first half of the 1970s, driven by monsoon failures and the global oil shock, culminating in food shortages, workers’ strikes and, finally, the Emergency in 1975. This period of upheaval influenced a generation of writers, who radicalised modernist Malayalam literature. Poet-critic K Satchidanandan, who introduced the first comprehensive collection of Sukumaran’s short stories in 1984, wrote that Sukumaran politicised Malayalam modernist literature with his radical sociopolitical vision and ethical commitment and modernised politics with his understanding of modern man’s predicament and radical sensibility.

Sukumaran, of course, was representative of a generation of writers who were responding to the political upheaval unleashed by the Naxalite movement. What, however, distinguishes him from his equally sharp contemporaries — Pattathuvila Karunakaran, UP Jayaraj, among short story writers — was his complete identification with the politics that informed his writing. When he started writing in the mid-1960s, his style and themes were closer to the generation of early modernists who preceded him, MT Vasudevan Nair being the most prominent of them. However, his involvement in the trade union movement transformed both his life and fiction. The militancy that informed the politics of his writing was shaped by his work in the union; the writer, too, may have influenced the transformation of the self-effacing clerk at the accountant general’s office in Thiruvananthapuram to a combative unionist.

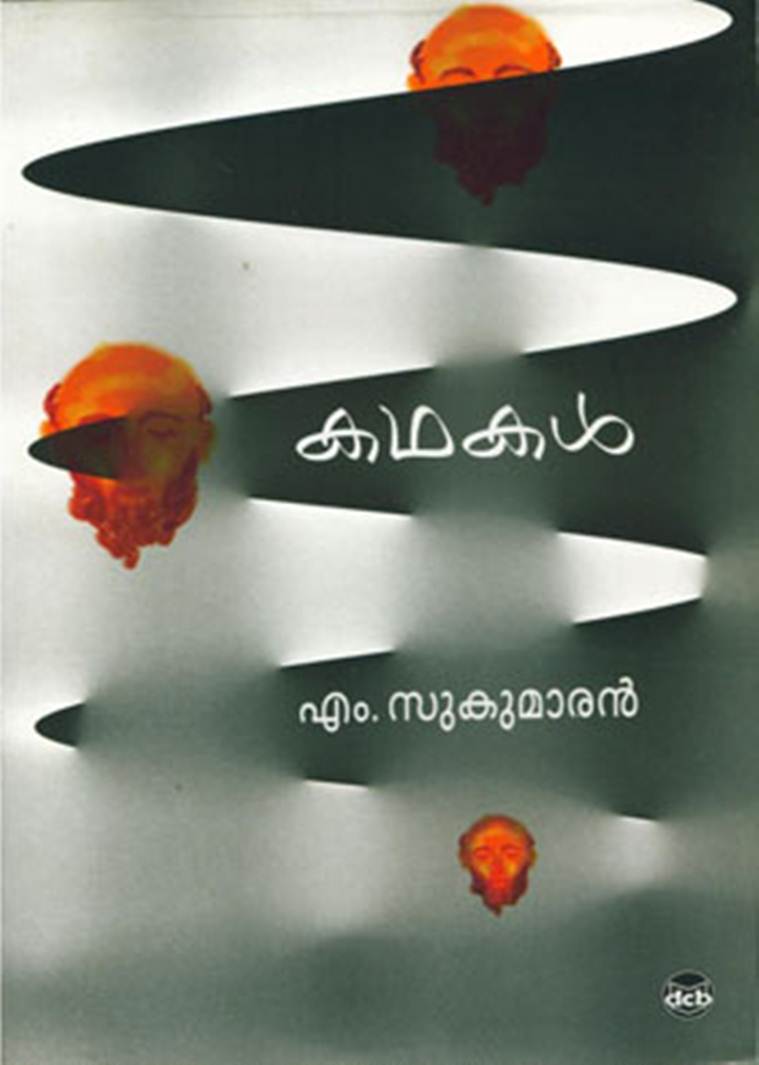

The cover of Kathakal, by M Sukumaran.

The cover of Kathakal, by M Sukumaran.

Following the all-India strike in 1974, Sukumaran was dismissed from service by a presidential order. The push to penury, reports of radical action, and the Emergency only sharpened the political edge of his stories; the political being in him was aware that the ground beneath was slipping but his characters insisted, “strive on, strive on”. In the dark months of the Emergency, his stories assumed the nature of allegories and parables to become epic tales of dissent and resistance. Short stories like ‘Chorus’, ‘Saga of history’, ‘Gallows are for us’ and ‘Memorials of the undead’ were discursive tales of a process and a movement, constantly drawing from the past to historicise and politicise the contemporary moment. Occasionally, there was a hint of the impending crisis: “Have I slipped into sleep even before the story has ended? The crows have started cawing. The roosters are also crowing. The night of the one in custody is ending. The night of the one to be caught is beginning. One is interested to know. How long for the sun to rise?” The sun never rose.

Sukumaran, the writer, did not survive the night of long knives. In ’82, he wrote Seshakriya (The Last Rites), which spoke about the marginalisation of a Dalit activist by the caste bureaucracy of a communist party. The CPM promptly expelled Sukumaran from the party. Years later, he explained in an interview why he stopped writing. “I had travelled the distance I could with political beliefs and the creative process. If one of the bullocks fall, how can the cart be pulled? By 1982, I felt I had said everything that I had to say,” he said.

Sukumaran could have embraced new ideas, become a part of the new social movements and so on. Or, he could have wallowed in a politics of nostalgia. He refused both. Somewhere in his journey, the writer in him had assumed the self of an idea, a movement. When the idea died and the movement failed, he withdrew into silence. A decade later, in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Sukumaran returned with a long story, Pithrutarpanam (Offerings to Ancestors, published in 1992), where an old communist, distraught at the end of a dream, ends his life. His daughter, however, keeps reminding herself: “One must not tire, one must not tire”. Some years later, he wrote a novella, Genitakam (Genetics, published in 1994), on the corruption and bureaucratisation in communist parties, and the disconnect between ideals and praxis.

Politics made Sukumaran and it consumed him. Writing for him was a commitment to a movement and his fiction was a window to a time when the individual self was subsumed in the collective. In an atomised society, Sukumaran preferred to watch politics from the sidelines and chose silence over speech. And, his silence had a rare eloquence.