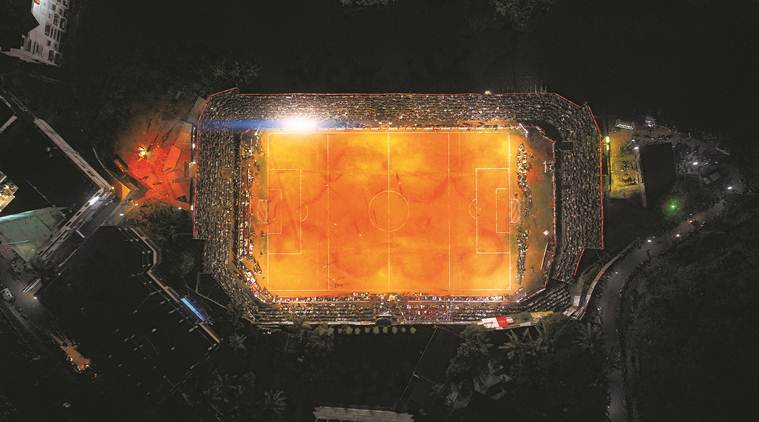

A drone captures the action at the All-India Koyappa Sevens Football Tournament in Koduvally. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith.

A drone captures the action at the All-India Koyappa Sevens Football Tournament in Koduvally. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith.

The floodlights on the six iron poles illuminate the makeshift football stadium on the banks of Poonur river at Koduvally in Kerala’s Kozhikode district. Laser beams cut through the din of the music and the wispy smokiness of the induced fog. Around 5,000 men are perched on a wooden gallery, two drones with cameras hover above. Pitch-side sprinklers spray water to settle the dust below, before recoiling their heads back underground. Around 7 pm, the players — of teams Mediguard, Areekode; and Lucky Soccer, Aluva — enter, to fireworks. The 36th edition of the All-India Koyappa Sevens Football Tournament kicks off. Starting March 27, the tournament will keep football lovers enthralled for a month. Just one of the 63 official and scores of unofficial ‘Sevens’ tournaments that will be held over six months at rural grounds in Kerala’s Thrissur, Malappuram, Palakkad, Kozhikode, Kannur and Kasaragod districts.

On April 1, when the Kerala football team won the Santosh Trophy in Kolkata after 14 years, the celebrations reverberated in these parts. Not only did most of the players hail from here, they also forged their careers in the same Sevens format. The region’s passion for the truncated version of the game is also at the heart of the recent critical and commercial Malayalam hit Sudani from Nigeria — about a football manager and his bond with his African import, who gets injured. Night after night, seven players per team (as opposed to the traditional 11), take on each other over a field 60 m long and 40 m wide (as against the standard 120×80 m), for an hour (as opposed to 90 minutes). Last season alone saw 978 such matches.The craze particularly engulfs the Muslim-majority Malappuram and neighbouring Kozhikode, where 8-10 deck galleries of bamboo and areca poles are propped up on dry river beds and paddy fields after the harvest in December-January. Promotional banners with photos of young African footballers crop up around villages. The fiesta lasts till the end of May, when the first monsoon showers leave the grounds slushy, muddy and unfit to play.

The sport was brought to the region nearly a century ago by British officers of the Malabar Special Police, which had a camp in Malappuram. The locals, particularly Muslims, soon took to it. But they had only paddy fields as grounds, giving birth to the Sevens version of the sport. For years, says R Vinayan, 70, patron of the ‘Sevens Football Association’, the shorter format did not receive recognition from state and national football associations, hindering the players. Then, in the 1950s, national players coming for the Sait Nagjee Football tournament in Kozhikode started seeking additional income in the local Sevens. “During the 1950s and 60s, local players were denied a chance as the football clubs of Kerala hired players from Bangalore and Goa. Such players moved en masse to the Sevens despite the threat of a ban,’’ says Vinayan, who owned the team ‘Black and White’ for nearly 50 years.

Nigerian Uzor Onyekschi with the owner of FC Perinthalmanna V P Saji (extreme left). Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

Nigerian Uzor Onyekschi with the owner of FC Perinthalmanna V P Saji (extreme left). Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

By the 1970s and ’80s, the matches had moved into enclosed grounds, with coconut palms serving as borders, and entry being made paid. In 1983, the Kerala Sevens Football Team Managers Association was formed to ensure that organisers paid teams the promised amounts.

Former Indian footballer I M Vijayan says the Sevens football groomed players like him. “There would not be a single professional footballer in Kerala who hasn’t played in the Sevens,’’ he says. V K Afdal, 22, a striker in Kerala’s Santosh Trophy team, started out with the Sevens played in his village of Olipuzha in Malappuram. Showing the ground, just a stone’s throw from his house, he says, “A Sevens player is never shy of big crowds as he is used to playing before these galleries. Sevens is also faster,” says Afdal.

Jiyad Hassan, 25, another member of the Santosh Trophy team, has been a Sevens player for four seasons. “Sevens provides an opportunity for a lot of players who would otherwise have to sit idle. It has also brought the quality of the African players’ striking and dribbling skills to our grounds,” he says. V A Narayana Menon, a football coach and one of the promoters of the I-league side FC Gokulam, says the Sevens sustained the love for the game in the absence of football clubs and proper tournaments in Kerala.

Farook Pacheri, secretary of the Perinthalmanna-based Khadar Ali Sports Club, says the Sevens circuit is also known to plough back some of its profits for charity. Giving the example of his club, which has been conducting the Khadar Ali Sevens for 47 years and generated a profit of Rs 15 lakh last year, he says, “We gave the money to treat the poor and for marriage of destitute women, apart from for football coaching for school students.”

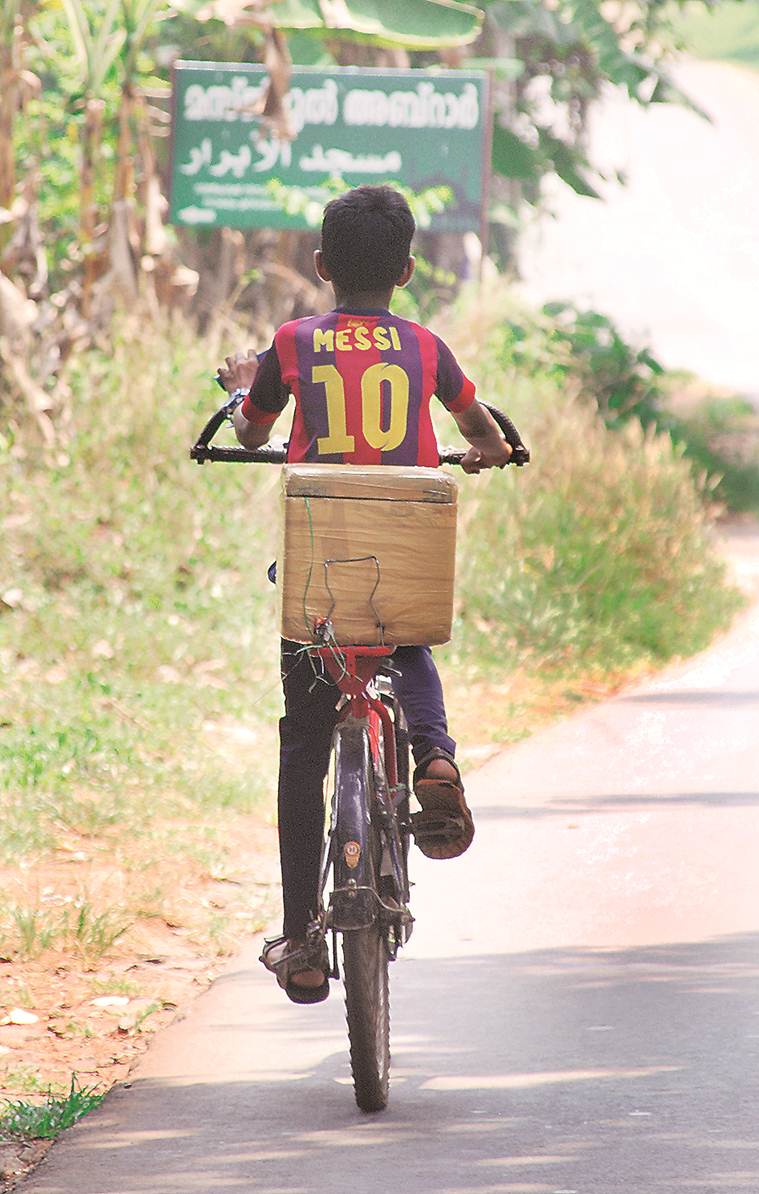

A child sports a Messi jersey at Ucharakadavu in Malappuram. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

A child sports a Messi jersey at Ucharakadavu in Malappuram. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

P K Abdul Vahab, coordinator of the Koyappa tournament conducted by Koduvally’s Lightning Club, believes the tournaments have been able to sustain themselves by becoming more professional with the times. “This year, we introduced drone cameras for live recording of matches. We have a huge electronic score board at the stadium now,” he says.

Kerala Football Association (KFA) president K M I Mather, however, is muted in his opinion about the Sevens. “Ten years ago, we had a discussion with FIFA on the status of the Sevens in Kerala. As per their suggestion, we consider it village football,” he says.

The 36 official teams that are playing the Sevens this year are registered with the Sevens Football Association (SFA). These include two from outside the state — FC Goa and United FC Mumbai — and as many as 14 from Malappuram. The tournaments are conducted by clubs, which themselves need not have a team. The participating teams are sent invitations based on their performance in the previous season.

Al-Minhal Musthafa, treasurer of the Valanchery Football Association, says the budget for a month-long tournament is around Rs 25 lakh. “A 10-deck gallery costs around Rs 6 lakh to build. The rest of the money is required to pay the teams, match officials and other expenses. We need

Rs 75,000 a day. From tickets — each Rs 50 — we earn Rs 30,000-50,000, but the major source of funds are local brands and business houses,” says Musthafa.

V K Afdal, 22, a striker in Kerala’s Santosh Trophy team, started out with the Sevens at the ground in his village of Olipuzha in Malappuram. The format helps players adapt to big crowds, he says. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

V K Afdal, 22, a striker in Kerala’s Santosh Trophy team, started out with the Sevens at the ground in his village of Olipuzha in Malappuram. The format helps players adapt to big crowds, he says. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

“While fixing the schedule, we ensure there is no all-India match in the locality, so as to ensure revenue for the organisers,” says Asharaf Bava, the SFA secretary, who also owns Super Studio Malappuram FC.

The Sevens teams are mostly owned by former players or business houses. The clubs are mostly based out of one-room tenements, and like the league, come alive only during the season. “My father Ambayathingal Muhammed was one of the earliest football players at Areekode. Our family owned a medical shop named Mediguard. Hence, when I floated a Sevens team, we named it Mediguard,’’ smiles A M Habeebulla, 52, teacher at an upper primary school, who launched his team in 1997.

Asharaf Bhava, the owner of Super Studio, Malappuram, who also acted in Sudani from Nigeria, says the huge crowds make it easy to attract sponsors.

Rujeesh K, 36, who manages the Facebook pages and WhatsApp groups of the official Sevens tournament, says teams keep changing hands. “A good banner would fetch at least Rs 10 lakh. And with the SFA putting a ceiling on number of teams eligible for the Sevens, the best option is to buy an existing team,’’ says Rujeesh.

If at least Rs 6 lakh is needed a year to maintain a team, a chunk of the expenses are met by seasonal sponsorship. The teams get an average appearance fee of Rs 16,000 in the early rounds; for popular teams, this is higher. As a team progresses, so does the prize money. Winners eventually get between Rs 35,000 and Rs 40,000.

The post-harvest paddy field doubles up as a football ground at Oravampuram near Pattikkad in Malappuram. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

The post-harvest paddy field doubles up as a football ground at Oravampuram near Pattikkad in Malappuram. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

The biggest expense is the upkeep of players, a mix of foreign and local talent. A player is paid Rs 2,000-5,000 for a match, depending on past performance.

The controversy over Nigerian actor Samuel Abiola Robinson accusing producers of Sudani from Nigeria of racism is one-off. One of the highlights of the Sevens in recent years is the presence of Africans — known generically here as “Sudanis” (a throwback to when traders brought slaves from Sudan to the Malabar coast).

The SFA has increased the number of foreigners that can be fielded in a match to three this season. Most teams have four to five Africans on their roster.

Abdul Jabbar, the manager of Royal Travels FC, traces the trend back to the mid-’90s, when a number of African students were in colleges in the region. “Around that time, Sevens teams in Kerala handpicked some ‘Sudani’ students of Calicut University,’’ says Jabbar.

Those students brought in friends from other parts of the country. The local clubs also began to scout the number of journeyman African players who began turning up in the country, particularly to try their luck with football clubs in West Bengal.

With no cap on the number of foreigners in a Sevens team, football team managers in Africa soon started doubling up as agents for the Kerala clubs.

This season, Jabbar says, at least 250 African players are camping in the region, many of them veterans of the Sevens. From Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Liberia and Cameroon, they can make anywhere between Rs 1.5 lakh to Rs 3 lakh in a year.

The foreign players are given seasonal contracts and free accommodation and transportation to the tournament grounds. The teams also pay their visa and ticket charges. Sometimes, like in Kasaragod district, players have to travel 200 km for a game.

K Rashik, the owner of Lucky Soccer, Kotapuram, Malappuram, says foreigners are selected at the end of the season in May, with YouTube and WhatsApp changing the game. “We can now directly interact with interested foreigners, who send us footage of their performance.” At Kotapuram village near Kondotty in Malappuram district, striker Deco Eric Toe with Lucky Soccer club shares a house with four other Africans. The 27-year-old from Liberia says they are drawn to the league by the monetary benefits. “Most of us have families to support. This season alone I could send home about $2,500,” says Toe, who earlier tried his luck in the lower leagues of Cameroon.

A packed gallery at Koduvally watches Mediguard, Areekode, take on Lucky Soccer, Aluva. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

A packed gallery at Koduvally watches Mediguard, Areekode, take on Lucky Soccer, Aluva. Photographs: T Mohandas and K Shijith

Mohamed Abdullasi Doumbia, 32, a veteran of the Sevens circuit, lives at Anchachavadi village near Kalikavu. A native of Ivory Coast, he says, “Last year, I took home almost Rs 3 lakh. Two years ago, I started a used-car business in Ivory Coast with the money I earn here.” He has also come to love Kerala food, especially biryani and Kerala parotta.

A player for the Smak Media FC team, Doumbia, however, admits that most African players follow monotonous lives outside football. “We do not go out for any entertainment. We return to our quarters late at night or early in the morning and sleep till noon. On non-match days, we jog for an hour in the morning before sleeping again. At noon, we cook. If the team has provided us a TV, we watch sports channels. Otherwise, we just listen to music or watch movies on our phones,’’ he says.

In the past, the African players stayed back in Kerala after the Sevens season. But following some intervention by the Foreigner Registration Office, they now return home in the off-season.

Muhammed Nabeel, 22, who plays with Mediguard, says the presence of the African players has changed the game in another manner, by making it a more physical contest. “The Africans play hard. They also want the team to win at any cost and get emotional and angry if we make fouls or miss goals. But once outside the ground, they harbour no ill-feeling.”

At the same time, a majority of the local players picked for the Sevens remain daily wagers, who head to the game after a day’s work. Some even work in the Middle East in unskilled or semi-skilled jobs in the off season. In a small room in a wayside lodge at Pandikkad village in Malappuram, Muhammed Faris,19, is pulling on the jersey of KFC Kalikavu. A wall painter by day, Faris has just returned from a construction site. “This is my first all-India Sevens season,” he says. “For three years, I had been playing in the local Sevens at Kasaragod and Wayanad districts. I was paid Rs 700 a match then, I am now getting Rs 2,000.’’

Faris was also part of the MSP School team in Malappuram that featured in the Subroto Cup in 2015.

Faris says he can’t give up his day job as he is the sole breadwinner of his five-member family. “I earn Rs 700 a day from painting. If the match is at a faraway ground, I skip the work. I also need money to buy boots for the next under-19 I-league tournament,” he adds.

Muhammad Irfan, 22, also with KFC Kalikavu, says the fear of injury weighs on his mind. “I need the Sevens to feed my family. Last year I played with a team in Kasaragod for Rs 500. This season, KFC Kalikavu paid me Rs 1,500 per match… Even senior players have no financial security,’’ says Irfan, a native of Kalikavu who works as a light assistant for a videographer, to supplement his income.

Having played in the Sevens for the last 14 years, Muhammad Ismail, 37, says, “My wife, three children and I survive on the Sevens.” He has been with FC Perinthalmanna for the last three seasons, and also runs a sports goods shop in Perinthalmanna with teammate V Hyderali.

Abdul Salam P, 25, who has been with FIFA Manjeri for the last eight years, believes the presence of foreigners too has affected the chances of local players like him. “This season, I haven’t played for 22 days after sustaining a leg injury,” says Salam, a goalkeeper, who works at the local fish market when there is no match.

But he would have it no other way. “Through my football, I have married off my sisters and am now looking after my mother, a widow,” says Salam.