A group of rafoogars during the workshop on the sidelines of the exhibition

A group of rafoogars during the workshop on the sidelines of the exhibition

Almost a century-old pashmina square shawl, with embroidered motifs that look like tiny insects swimming in a white sea, took Intekhab Ahmad from Najibabad (Uttar Pradesh) — an expert at the traditional skill of darning or rafoogiri — around six years to repair and bring back to life after it was damaged by bugs. Right next to it, at the art gallery of Delhi’s India International Centre (Annexe), rests a 200-year-old Hyderabadi shawl, with intricate designs in yellow, green and purple, touched up at places it was torn, by other rafoogars from the same locality as Ahmad.

These works by rafoogars comprise the exhibition “Making Visible: The Rafoogars and the Journey of a Shawl” that lends an insight into the role of rafoogars in the restoration and preservation of shawls and textiles over time.

Squinting their eyes, viewers at the exhibition carefully inspect the borders of a beige hand-stitched pashmina Choga, a men’s coat with long sleeves in Mughal style, that was restored around two years ago. Fine lines running through the piece serve as a doorway into the spaces where the fabric has been stitched using needles and matching threads and restored.

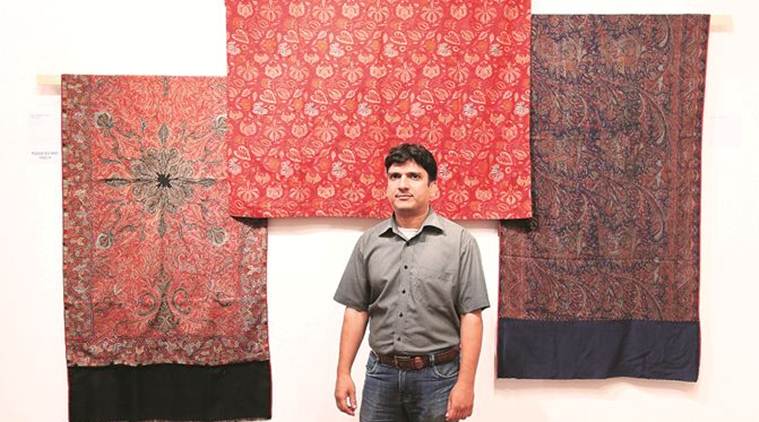

Nadeem Anver with some of the shawls he has mended

Nadeem Anver with some of the shawls he has mended

“This is not simply a collection of beautiful shawls and garments but the aim is to show how old pieces are transformed, which otherwise would not be used, into something new that everybody can enjoy. Rafoogiri itself is such a skilled art. It is also about how to place the colours and how one cuts and makes the designs fit. Rafoogars have a highly developed aesthetic sense with a knowledge of tradition and are artisans in their own right. These days, we talk about no waste but this skill has been there for centuries. The rafoogars don’t won’t waste a single thread of a textile piece because they will attach it to another textile that they were darning,” says Purnima Rai, the exhibition designer and former President of the Delhi Crafts Council.

At the opening of the exhibition on Tuesday evening, during the Rafoogar Baithak organised within the gallery, Nadeem Anver, 35, who learnt the craft during his summer holidays as a 13-year-old, points out that the main challenge is that it requires sitting endlessly throughout the day, while maintaining a stiff back posture.

“Due to the level of intricacy and precision involved while restoring the fabric, the vision of many rafoogars diminishes over time,” he says. He also believes that the survival of the craft is threatened in this age of computers and mobiles, and with their children choosing to pursue different professions in place of the traditional craft. “The next generation does not want to pursue the profession. Since we are not getting much work now, we would want our children to study and get other jobs. The fashion has also changed. Not many people wear shawls these days because they are now wearing stoles and scarves instead,” he says.

Curator Priya Ravish Mehra

Curator Priya Ravish Mehra

The brain behind the exhibition, curator Priya Ravish Mehra, an artist, textile designer and researcher, has worked with rafoogars for her textile-based artworks for over 13 years. In an earlier interview for her show “Presence in Absence” at Gallery Threshold last year that also paid an ode to the rafoogars, Mehra stressed on how customers, when speaking to the darners in their neighbourhood markets, only enquire about the money that will be required to repair their cloth but do not give the required respect for these craftsmen. Classifying them as an integral part of our art and culture, she aptly points out that the urgent question posing the craft is not merely its revival but rather the survival of the craftsmen and the continuity of the rafoogars’ “invaluable, irreplaceable and indigenous knowledge”.

Having seen rafoogars at her grandparents’ household since childhood in Najibabad, home to some of the best darners in the country, Mehra believes much like how the success of their work is in its invisibility, these rafoogars, too, have remained largely invisible. Hoping to bring this out in some way, the show is a reflection on whether the society is interested in the philosophy of repair, reuse and giving a new lease of life to an old, torn and worn-out piece.

The knowledge of rafoogiri is passed on from one generation to generation within the community. The rafoogars survive by doing the simplest mending in bazaars, beginning at a cost of Rs 500. Anver hopes that the exhibition helps them garner more repair work and get them in touch with customers. “Because when people get to know about it, customers can directly talk to us. A lot of showrooms take work from customers who want their shawls repaired. They then call us to do the work and take away half of the money. We don’t get what is due. Through this exhibition, we hope to directly connect with customers,” he says.

The exhibition is on till April 17 and workshops with rafoogars will be held till April 15, 11am-6pm. Entry is free