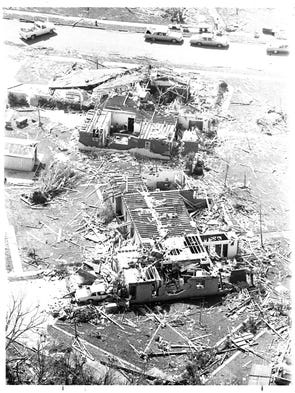

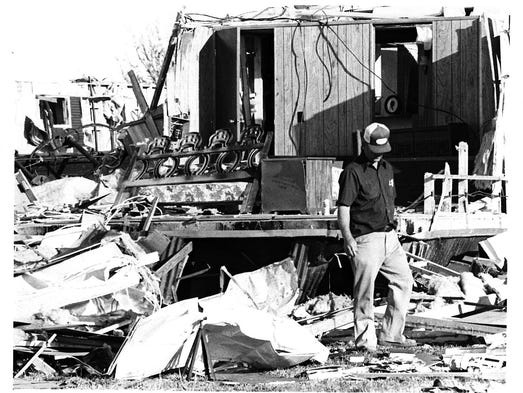

Years after the April 10, 1979 tornado in Wichita Falls survivors tell their stories of what happened that day. Lauren Roberts/Times Record News

"Terrible Tuesday" is a day that is remembered vividly by those who experienced it. The day is also known as the Red River Valley Tornado Outbreak with three super-cell thunderstorms producing 13 tornadoes that touched down from north Texas to Oklahoma.

Early on April 10, 1979, the National Weather Service sent out warnings of possible severe weather.

"Of course, almost 40 years ago you didn't have the weather technology or expertise that we have now," Lynn Walker, former KAUZ news director and lead anchor, said. "So we weren't going to get as specific a warning or early a warning as we would nowadays." Walker would later serve as city editor for the newspaper.

By the afternoon, the Wichita Falls area was put into a tornado watch. To the west of Wichita Falls was a large super-cell thunderstorm and behind it was a smaller super-cell thunderstorm. The larger storm stuck Vernon where a F4 tornado, the second-highest rating possible, touched down and caused 11 deaths.

That storm would move north of the Red River and head to Lawton, Okla., where three more people would be killed. A smaller storm began to move toward Wichita Falls. When it was over Seymour, the storm dropped down an F2 tornado as it continued tracking towards Wichita Falls.

A third super-cell thunderstorm started near Harrold and would travel northeast to Grandfield, Okla., and end south of Marlow. That storm would produced a tornado that was on the ground for 64 miles.

Tornadoes touch down

Lee Anderson was on the regional staff at the Times Record News during Terrible Tuesday.

"For me it was a typical work day," Anderson said. "For some reason, I left the office at maybe 4 o'clock that afternoon."

Anderson never thought that a tornado would be a possibility that day. Not severe weather or even rain. At home he decided to take a nap, and as he was dozing, famed farm editor Joe Brown called him to ask if he wanted to go to a fatality on U.S. 287 between Harrold and Oklaunion, which is east of Vernon.

"We see this 18-wheeler and a car on the side of 287 headed in the direction of Vernon. They both pulled over to the side of the road because they could see a tornado coming," Anderson said.

The man and woman from the car had hid underneath the 18-wheeler, and the storm picked it up and slammed it back down.

"Unfortunately this little lady was crushed by the wheels. She was deceased when I got there," Anderson said.

A highway patrolman suddenly said that he needed to get to Vernon and started running to his patrol car. Anderson was able catch a ride into Vernon with the patrolman and asked him what was happening.

"He said Vernon's just been devastated by a tornado." Anderson said, "Before we got to Vernon I could tell that the city had been hit real hard. Particularly the south and east sides of town."

Once in Vernon, the patrolman let Anderson out. With no other way to get around he started walking, talking with survivors and taking photographs. He went to the National Guard Armory to interview law enforcement, medical personnel reporters who worked in Vernon and other officials.

Eventually he headed to the funeral home after meeting back up with Joe Brown. It was there that he tried to call the newspaper in Wichita Falls.

"I kept calling and trying to get a hold of the newspaper to to let them know what had happened in Vernon because in my mind at that time I thought I had the biggest story imaginable," Anderson said. "I finally got through to the editor of the paper. His name was Don James and he said, 'Lee, Wichita Falls had been hit. It's been hit hard. Your wife and kids are OK.'"

Anderson said he noticed something strange. Normally you can see the bright lights of Wichita Falls from on the other side of Iowa Park, he recalled, but it was total darkness.

"It was a very eerie experience," he said.

Once he and Brown reached the newspaper, they had to write on manual typewriters by candlelight.

"That's when it started sinking in to me how bad it really was here," Anderson said.

With footage from the Vernon tornado in hand, KAUZ scrambled to get a newscast on the air.

"Just as we were going on the air at six o'clock – just beginning the news of this tragedy – our sportscaster Bill Jackson came into the studio from the back door and he was white as a sheet," Walker said. "He said there's a tornado out the back door and it's coming this way."

Walker said the two options were to stay on the air with the tornado coming at them and try to warn people or get under the desk.

"Didn't have to think about that too long because the tornado that stuck Wichita Falls had hit the major power trucks and severed power. The television station went off the air. We went out the back door and there it was," Walker said. "A huge tornado. It looked like it was bearing down on the television station on Seymour Highway."

At that point they jumped into cars and got out of the area. He said they got on Seymour Highway and headed downtown.

"At some point I realized that the tornado was not heading toward us," Walker said. "It had been so large that it looked like it was."

When they noticed the tornado was to the south, they drove towards Sikes Senter Mall. Before they got to the mall they began seeing the damage the tornado caused to the area. Homes were destroyed, cars were toppled with some in Sikes Lake.

"By the time we got to Sikes Senter Mall, we were seeing the walking wounded in the parking lot there," Walker said.

Walker's co-anchor, Kay Shannon, had a background in medicine and she wanted to get out of the car to help the wounded.

"By then we could see the extent of the damage. At the time Kemp Boulevard had a drainage ditch down the center of it and it was full of cars. Faith Village, the neighborhood to the west of Sikes Senter off of Kemp was totally flattened," Walker said.

Power wouldn't be restored to most of Wichita Falls for a few days which left many people in the dark as to what was happening in the aftermath of the tornado.

At KAUZ the chief engineer managed to get some power from a generator into the station so camera batteries could be charged and work lights could be used. Walker said the engineer was also able to get the lights turned on at the Channel 6 tower and most importantly was able to power KLUR radio.

"Throughout that night several of us sat on the floor in that little hut there broadcasting what little news we could. KLUR and KTRN radio were the only two media on," Walker said. "The town was virtually black except for some power that was on in the north area of town."

The Williams Family

Kristie Smith was 6 years old on Terrible Tuesday. She was home with her 8-year-old brother, Shane, and mother Karen Williams. Karen and her husband, Freddie, worked at Sheppard Air Force Base.

"We had warnings and watches all day long and we had received several pyramid messages that, you know, the clouds were building, the storms were getting worse," Karen Williams said. "At that point I think probably at 2:30 or three o'clock I went by the fire station where my husband was and I said, 'I'm going to get the kids from the babysitter and I'm going home.'"

At the time Williams believed that the storms were going to move northeast rather than moving toward where they lived on the southeast side of town. Once she got home with her children, she prepared dinner for them and also got prepared in case a tornado came.

"I actually had an old mattress that my grandmother had given me for that very purpose and had pulled it into the hall, but we were still doing our evening things," Williams said.

Not long after a neighbor came over to tell Williams she should have her kids go inside the house.

"It didn't seem bad until it was there. I don't remember thinking at any point there could be a tornado. We were going about our business and all of a sudden they were like you need to take cover," Smith said.

Williams said that around 6 p.m. she heard the sirens start to go off.

"We looked at the TV and it said there's a tornado on the ground in Wichita Falls, take cover and they went off the air. So I flipped on a radio and it was the same thing. It's here and they went off the air," Williams said.

"In a tornado briefing that we had at work, they said you need to talk, laugh, scream, sing, whatever you want to do to keep your ears open so your ear drums don't burst," Williams said. "So I said we are going to sing 'Jesus Loves Me' and we're going to sing it as loud as we can sing it and we're going to sing it until I tell you to stop. That was the easiest thing for me to do because I knew I couldn't make them laugh. I wasn't going to be telling any jokes at that point."

After that tornado passed, Smith's mother went to take a look outside and saw another tornado headed their way. At that point their house was still intact and had a roof.

"Once the second one came through you could feel your ears popping and my mom was still making us sing 'Jesus Loves Me' mainly because I think we were just trying to not hear all the noises and our ears were popping. But you could hear things hitting and cracking and breaking," Smith said.

"There was so much pressure on your head. You could tell when the roof went. It was almost like a cereal box ripping off and that pressure just kind of subsided," Williams said. "I couldn't stand to play the radio in the truck for about three weeks because my ears still hurt."

The second tornado left the house they were moving out of destroyed. But some things were left untouched by the tornado. The dinner plates, glasses and silverware that had been set on the table before the tornadoes hit were still there. Williams' wedding rings were still sitting on the windowsill from when she had done the dishes. A camera that had been left on top of their refrigerator was still there. She would use that camera later to take photos of the destruction.

"There was insulation in all of our stuff so we couldn't even use it. The clothes and everything in boxes had insulation in them. The food had wood pieces inside of them," Smith said.

"We were all barefooted," Williams said. "My son's coat was in the hedges about two yards down so I went down there and got him that coat."

With her car wrapped around a tree, all they could do is sit on the curb and wait for help.

"It was sprinkling and cold and you're just terrified because people are running up and down the street that you don't know and it was pretty scary," Williams said. "But finally looked up and saw my husband running down the street. So I thought OK you can do this now, I'm going to cry. Until that point I didn't really do that because I had to take care of my son and daughter."

Thirty-nine years later, all that remains of their house on Glendora Drive is the foundation. The Williams' keep a close eye on storms and stay prepared.

"Now I'm kind of obsessed with weather. My husband thinks I'm crazy," Smith said.

Aftermath

One week before Terrible Tuesday the Wichita Falls emergency corps held a mock disaster drill. Volunteers practiced moving victims from rubble with rescue operations directed by radio from a command center. But, according to the April 11, 1979, article, the planning went for naught.

"There was one difference, and it was a big one," city attorney H.D. Hodge said. "We lost all our damn power."

At the downtown police station, those who were supposed to direct disaster operations were forced to sit with silent radios. The townspeople were left to fend for themselves like blind men lost in a wilderness.

More than 1,700 people were injured and 6,000 families were left homeless in Wichita Falls. The final estimate of property damage was $700 million.

One of the challenges faced after the tornado was loss of power. With the main lines cut, it took days for power to be restored to all of Wichita Falls. Price gauging was short lived as the city made sure that those caught participating in the activity would be prosecuted.

Another challenge came during the recovery effort. In a April 20, 1979 Wichita Falls Times article the Texas Attorney General Mark White warned residents in Wichita Falls and Vernon to be wary of fly-by-night builders and contractors moved into the area.

"It is unfortunate that this type of warning must be given," White said, "but our experience is that a small element of our society will use unlawful and deceptive practices to take unfair advantage of the victims of a disaster."

Susan Tyner lived in Dean and was 14 years old at the time of the tornadoes. Her stepfather died of a recurring cancer in 1980.

"So my mother had to deal with the builders and they took her money and ran off," Tyner said. "So this 90 pound Japanese woman learned how to do carpentry and she redid the house herself."

Volunteers came from all over the country and even Canada to help rebuild. Many Mennonites came and would help rebuild homes for free. One couple Mr. and Mrs. Norman Scott spent their honeymoon helping the disaster victims.

In 1978 Wichita Falls was the host of the first NCAA Division I-AA championship game. The tornadoes destroyed the press box and lights at Memorial Stadium, which lead to the Pioneer Bowl being moved to Florida.

Forty one of 45 deaths were due to trauma; 25 died because of vehicles, eight were outdoors, four were inside public buildings and four were inside private homes. In 16 of the vehicle related deaths the victims tried to escape the tornado's path only to be caught by the tornado. The homes of 11 who tried to escape didn't suffer major damage with some undamaged.

Tornado Victims names and birthdates

Christopher Paxton Cox - June 10, 1980

Kari Marcia Swift - April 26, 1973

Audra Michelle Swift - Aug. 11, 1968

Richard Austin Shearman - Jan. 30, 1966

Marianne Rene Graves - Aug. 22, 1962

Jay Paul Huffer - Jan. 23, 1962

Ember Hull - Nov. 21, 1961

Terri Lea Mahon - Nov. 2, 1961

Rhonda Jean Crooker - Aug. 1961

John Howard Spangler - June 25, 1959

Kelly Hull - Jan. 20, 1959

Becky Jewelene Standridge - Dec. 1, 1956

Nancy Lynne Rodawalt - Sept. 10, 1956

David Michael Liggins - May 29, 1952

Arden I. Turner, Jr. - May 26, 1945

Ronald Dale Harbour - Nov. 20, 1938

Esther Sue Corder - Sept. 8, 1938

Marie Isabel Saikowski - March 16, 1929

Edwin Hogue - March 19, 1929

Lola LaVirl Massengale - Feb. 22, 1928

Wanda Aston - Sept. 1, 1927

James Robert Aston - Feb. 27, 1925

Dolores S. Owen - Sept. 1, 1924

Margie Marie Nickell - July 5, 1924

Charles Ewing Gill. Jr. - Jan. 12, 1919

Floyd Greeling - Dec. 7, 1922

Cecil Leon Gough - May 26, 1920

Modena Laverne Norris - Dec. 2, 1918

Margaret B. Lynn - Oct. 5, 1917

John Peter Simons - June 25, 1917

Herman Dennis Norris - Sept. 4, 1914

Lawrence F. Litteken - March 5, 1914

Verna Harvick - March 5, 1913

J. B. Swindle - Aug. 18, 1911

Zanona Farnsworth Stone - Feb. 17, 1911

Grace Odom Thorp - Jan. 14, 1910

Annie Laura Glantz - Sept. 14, 1908

Dennis Nolan Thorp - March 25, 1908

Lawrence Chapman Smith - Feb. 20, 1907

Harry Lee Jones - Nov. 4, 1904

Pearl Jackson Morris - May 21, 1904

Kathrine McKee - May 29, 1901

Estes L. Smythe - Oct. 26, 1896

Donna Anderson

Deforest Clapp

Donna Shelton

Lou Anne Shelton

Mrs. Clyde Bagley

Gregory Martinez

Jack Avant

Cecilia Neson

Mrs. Jeanie Collins

James Norton

Mrs. James Norton

Vivian Kelly

Ben Williams

Edtor's note: Aside from the one-on-one interviews with witnesses and survivors, information for the article was found in Times Record News archived stories and the National Weather Service.