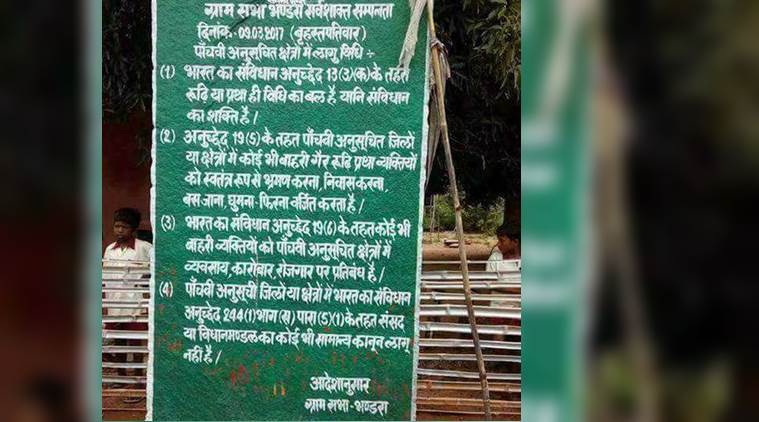

The Patthalgarhi inscriptions now declare autonomy of the Gram Sabhas under the Fifth Schedule, as a mark of tribal resistance against the Government. (Source: Swati Parashar and Anju O. M. Toppo)

The Patthalgarhi inscriptions now declare autonomy of the Gram Sabhas under the Fifth Schedule, as a mark of tribal resistance against the Government. (Source: Swati Parashar and Anju O. M. Toppo)

Patthalgarhi in Jharkhand has been making headline news, and it has been debated and contested for quite a few months now. Tribal villagers in remote parts of the state have declared autonomous village republics with patthalgarhi stone inscriptions issued by the Gram Sabhas. Through patthalgarhi, villagers have launched a non-cooperation movement against the government’s development plans and projects, even going to the extent of forbidding the entry of government officials or security forces into their villages.

Patthalgarhi is asking some tough questions of the Indian state and its beneficiaries who have never cared to look in the backyards where ‘development’ presents a dismal picture of rising inequalities and disempowerment of a large number of people. Concealed in this small act of resistance by the tribals is the story of the state’s apathy, the disillusionment with democracy and development and the reclaiming of traditional modes of self-governance.

Patthalgarhi is an ancient and common practice among the Munda tribe of Jharkhand, in which a large stone, much like a tombstone, with the inscription of the family tree of the dead person was placed on the graves. This was done in the memory of the ancestors to ensure that they would not be forgotten and was essentially a form of record keeping. Several Sasandiris (‘sasan’ is the burial ground where bones of the dead person are buried after cremation, ‘diri’ means stone) of different villages bear witness to the practice of Patthalgarhis. Besides the impression of the family tree, a few big stones placed in some villages also had the power and functions of the Gram Sabha carved on them.

This was done by the tribals, not only for territorial demarcation of the village boundaries, but also for highlighting the system of self-governance which has existed for ages. In the past, colonial encroachment of tribal lands was resisted by the Mundas through Patthalgarhi. Asked by the British to produce legal documents stating their right over the land, they carried these Patthals to prove their existence and ownership. Eventually the British accepted their claims and formally recognised the practice of Patthalgarhi.

The autonomous village republic with self-governance under the Gram Sabha is not only an ancient concept but also upheld by the Constitution. The Fifth Schedule of the Constitution lays down different sets of provisions concerning the administration and control of the Scheduled Areas inhabited by the Scheduled Tribes. It guarantees the protection and preservation of tribal traditional identity and autonomy.

The traditional Gram Sabhas which have existed in the Fifth Schedule Areas, have always had an informal mechanism for dealing with the daily lives of Scheduled Tribes based on their culture, customs, traditions etc. The Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 or PESA further strengthened self-governance through Gram Sabhas and offered protection to the tribals against the onslaught of neo liberal development which deprived them of their land and traditional livelihood.

With the enactment of this Act, no mining leases could be given or industries set up in the protected areas without the official consent of the Gram Sabhas. Patthalgarhi was carried out all through the 1990s in many villages to emphasise the importance and power of the Gram Sabhas. This voluntarism of the village republic hardly met with any opposition from the governments in the past and the latter implemented policies through the Sabhas. However, in recent times Patthalgarhi has been declared unconstitutional and deemed an act of open defiance.

The problem erupted last year soon after the Jharkhand Momentum global investors meet in February 2017. Local tribal leaders argue that the government signed a number of MOUs and promised land to various companies. On this pretext, the government started a new ‘land bank’ policy in which it added thousands of acres of non-cultivable land to be given away to companies in the emerging development landscape.

The original Patthalgarhi inscriptions were marked on graves with details of the family tree. Photo credit: Swati Parashar and Anju O. M. Toppo

The original Patthalgarhi inscriptions were marked on graves with details of the family tree. Photo credit: Swati Parashar and Anju O. M. Toppo

Fearing that the government would try to take away their lands, inhabitants of tribal settlements across Khunti, Pashchimi (West) Singhbhum and Simdega districts have installed huge stone plaques and signboards that warn outsiders against entering, moving around or trying to settle in their territories. Reliable sources claim that this year, in the month of February alone, this form of Patthalgarhi was performed in around 40 villages of the sub-division of Arki, Murhu and Torpa with the mass support of the villagers.

Most of the Patthalgarhis in various villages outline the laws enforceable in these areas that come under the Fifth Schedule, as a reminder to the state that Gram Sabhas are supreme and powerful in these regions, and they cannot be governed by general laws. Police teams who have gone to these villages to remove the barricade of stone plaques erected by the villagers have met with stiff resistance from tribal villagers equipped with traditional weapons like bows arrows, axe, sticks and spears.

The Police Superintendent of Khunti, Ashwini Kumar along with 100 other government and security personnel was also taken hostage at Kanki Village in Khunti and had to remain in the villagers’ captivity until the next morning. Patthalgarhi has since become a major irritant for the government, ensuing ongoing debates also among the urban dwellers.

Tribals claim that the tradition is legal and constitutional and want their rights to be restored and all development plans to be designed by the Gram Sabha. A few villagers have also stopped sending their children to government schools and are opposed to any ‘development’ work under the supervision of government officials. On the other hand, there are also some villages which have not supported the ongoing patthalgarhi movement to avoid disrupting development measures, which, they feel, is the only hope for people still lacking basic facilities and infrastructure to live with dignity.

Sending police and security personnel is not the solution to what has now become a non-cooperation movement against the government in many tribal villages of Jharkhand. Blaming the opposition and tribal leadership will also not help.

This is a challenge to the state in the form of nonviolent resistance, but also an opportunity to rethink the exclusive development model and initiate a new dialogue with the villagers to get down to the basics of governance.

Tribals have felt excluded for a very long time now and it is their land, forests and livelihood at stake in this push for modernisation and development. A hostile attitude will push the villagers towards more hardline positions, which the state can barely afford while it is still fighting the Maoist insurgency in many areas.

Patthalgarhi may not be the cure but it definitely is the symptom of the ailing development narrative that has been peddled with much conviction by the political classes for a very long time now. All is not well in the backyards of the Indian Republic!

- The ‘Gharwapasi’ of Padma Bhushan Father Camille Bulcke

In a state where religious conversion has always been a highly sensitive and contentious issue and anti-conversion laws have been introduced by the government; people…

- Development’s new ally in tribal India: Sabka Vikaas, Sabka Vivaah

Several tribal communities have a long history of live-in relationships where couples cohabit out of wedlock and even have children. Most of these arrangements have…

- The case for colonialism raises an academic furore

The Third World Quarterly recently carried an article by Bruce Gilley, a professor of political science in the US, which not only glorifies colonial rule…