Security forces cordon off an apple orchard in Shopian. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

Security forces cordon off an apple orchard in Shopian. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

THE Facebook photo that marked the arrival of new-age militancy in Kashmir was taken in Turkwangam village of Shopian. In July 2015, almost exactly a year before he was shot dead, Hizbul commander Burhan Wani posed with 12 associates, carrying guns and with faces unmasked, and put up the photo on social media.

Police say Burhan and his associates travelled to Shopian from Tral, Awantipora and Pulwama to shoot the picture, because the small South Kashmir district had only eight local militants at the time.

On April 1, when 12 militants, four civilians and three security personnel were killed in one of the biggest anti-militancy operations in the Valley in the last decade, it was Shopian that lay at the heart of it. The deaths came in two operations in the district —11 of the 12 militants killed that day belonged to 10 of its villages.

If that Wani photo in Shopian symbolised the start of a new wave of militancy in the Valley, the district once known more for its golden apples now represents what has happened after. Records show a three-fold rise in militant numbers in Shopian in the last one year. From eight local militants at the time of Wani’s killing on July 8, 2016, the number now stands at over 46. While 29 militants, including 12 on April 1, have been killed in the district in this period in operations by security forces, the number of local militants still hovers around 25. Almost all of the dead militants took up arms after Wani’s killing.

Says a senior district police officer, who doesn’t want to be identified, “There is militancy everywhere in South Kashmir, but Shopian is an altogether different story.”

***

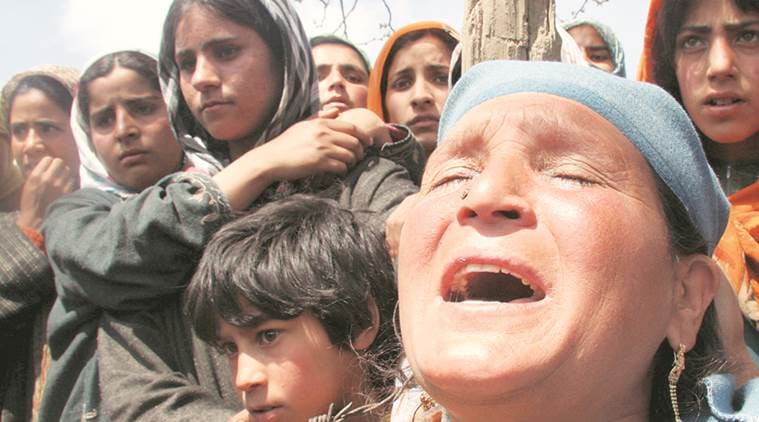

Relatives of one of the militants grieving after the April 1 encounter. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

Relatives of one of the militants grieving after the April 1 encounter. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

Four days after the April 1 encounters, Shopian is shut, with green-and-white flags fluttering in the air, its roads manned by masked young youths, as police, paramilitary and Army personnel keep a watch from behind sandbag bunkers. From mosques blare out songs extolling militants. Two children, around the age of 10, walk by with their cellphones playing Kashmiri ‘freedom’ songs.

Police sources say that in the encounters of April 1, if 12 militants were killed, at least six escaped. “The fact that 11 of them were hiding in one house (in Draggad) shows the confidence militants in Shopian have,” adds a top police officer dealing with counter-insurgency in the district. “We often get inputs of groups of five to seven militants roaming in different parts of the district.”

Another senior police officer puts the number of militants present in the district at any given time at “as high as 40”. “The problem is not just the increase in the number of local militants but also that militants from surrounding Kulgam, Anantnag and Pulwama too have moved into Shopian.”

Spread over 30,741 hectares, Shopian has a population of 2.6 lakh and is divided into two Assembly segments — Shopian and Wachi. It’s also relatively affluent, with money earned from the over 20,000 hectares under apple cultivation. Over two lakh metric tonnes of apples are produced here every year. Though the street protests of 2016 made it difficult to send the fruit outside, the fruit industry has remained largely unaffected by the militancy.

Its location has contributed to Shopian turning into a new militant favourite — it has as its neighbours Poonch (Jammu) in the south-west, and Pulwama and Kulgam districts, both of which have a good militant presence.

The twon of Shopian in South Kashmir (Express Photo)

The twon of Shopian in South Kashmir (Express Photo)

Shopian emerged on the radar of security forces almost immediately after Wani’s killing. In the protests that followed his death, South Kashmir remained out of bounds for days, with militants moving around unhindered and posting their videos. Before Shopian, Tral in South Kashmir and Sopore in the north had been militant strongholds.

Soon, Mehmood Ghaznavi, 40, a Hizbul Mujahideen ‘operations chief’ known for his tactical thinking, who was spoken of as Burhan’s successor, surfaced in his village Awneera in Shopian. Active since 1996, he had been presumed dead — having reportedly faked the death — before he was seen in Shopian addressing large crowds.

When security forces started a push into South Kashmir five months after Wani’s death, they left Shopian for the last. Then, in April last year, they had a rude awakening when they had to withdraw while trying to enter some villages in Zainapora area due to stiff resistance. It was after this that top officers of the Army’s Victor Force, that looks after South Kashmir, and police and paramilitary sat together to draw a new strategy.

In August last year, a joint team of police, Army and paramilitary forces surprised militants by cordoning off Awneera village, trapping nine militants inside, including Ghaznavi. After a gunfight of two days, Ghaznavi was killed along with two associates.

Then, in November 2017, additional forces were moved into Shopian. The CRPF sent a reserve battalion of nearly 1,000 men, while police despatched additional personnel of few hundred to various parts. The Army established eight new camps, including at Nagbal, Mantribugh, Pahnoo, Zainapora, Nagisharan and Chillipora.

Shopian Superintendent of Police Shriram Ambarkar Dinkar says the force operates on “a two-pronged strategy”. “One, where we organise public contact programmes and tell people that we are here to protect them. The second is to continue and intensify anti-militancy operations, though in a different form, with not just encounters but where we also bust modules. We will also act against people who are Over Ground Workers who run militancy in the Valley,” says Dinkar.

***

An army personnal walk during a gun battle between suspected militants and security forces in shopian, south of Srinagar. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

An army personnal walk during a gun battle between suspected militants and security forces in shopian, south of Srinagar. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

Within Shopian, security forces face the toughest challenge in over 60 villages bordering Kulgam, Anantnag and Pulwama districts — an area of dense apple orchards. Rambiara, a large stream that divides Shopian from Pulwama, is running dry these days. Last week, a group of teenagers walked into the stream, picked up stones and lined them along the road to prevent movement of vehicles.

“The villages are located at a tri-junction (of districts),” says a police officer. “Plus, the dense orchards provide cover, especially in the summer, when even sunlight can’t penetrate the trees. It is here that militants, including from neighbouring districts, meet.”

Police sources say that three Hizbul Mujahideen commanders separately commanded units in the district till one of them, Ishfaq Ahmad Thoker, was killed on April 1. Thoker was the only one among the 12 killed that day who had joined militancy before Wani’s killing. The 26-year-old, who became a militant in 2015, was commanding the area around his native village of Paddarpora.

Zeenat-ul-Islam, whose name figures in the Army’s list of most wanted militant commanders released after Wani’s killing, is believed to be running the operations in his native village Sugan and its surroundings. The Hizbul’s Kulgam commander, Altaf Kachroo, also moves around Shopian regularly.

Officials say Zeenat is in touch with Saddam Padder, who commands the Hizbul in Shopian and is active in his native village Heff and Shirmal. Both Zeenat and Saddam are ‘A++’ category militants in police books, with a cash reward of Rs 12.5 lakh each.

In the Keller region of Shopian bordering Pulwama, foreign militants of the Jaish-e-Mohammad, including fidayeen, are said to have set up base. Nestled in the Pir Panjal mountains, Keller is surrounded on two sides by dense pine forests, making it a difficult terrain for security forces. In recent months, the area has seen rise in militant movement.

Relatives and families take part in a funeral procession of an army soldier in Shopian of Kashmir. (Express Photo)

Relatives and families take part in a funeral procession of an army soldier in Shopian of Kashmir. (Express Photo)

But bar these handful of foreign militants, what marks the Shopian militancy is its “completely localised” nature, says a police officer involved in counter-insurgency operations — making their task all the more harder. The Hizbul is the dominating outfit, while a few are associated with the Lashkar-e-Toiba. “The militant commanders here don’t have even contact with their handlers in Pakistan. It is a closely knit network of relatives, friends and acquaintances. The people here are also religious and are ideologically wedded (to the ‘movement’).”

On April 5, outside a closed shop near the historic Jamia Masjid of Shopian, four youths in their early teens stood listening to the last conversation of Aetimad Ahmad with his father Fayaz Ahmad Malik. Aetimad was a militant for five months, before being killed on April 1. “I can’t ask you to surrender, I can’t tell you that,” Malik tells his son, as the 26-year-old informs him that they are trapped in a house and one of his associates has been shot. “Pray to God that He keeps you steadfast. Be brave. I will only tell you that you were God’s gift to me, and I am returning that.”

The conversation, in which Aetimad goes on to seek his father’s forgiveness, has gone viral in the Valley. One of the youths listening to it today on his phone, comments in Kashmiri, “By God, we have to become mujahid.” The other three stay quiet.

Police say religiosity is one of the factors for Shopian’s rising militancy. The district has had a long association with the Jamat-e-Islami — a politico-religious organisation that has been advocating Kashmir’s merger with Pakistan. Two of the Jamat founders in J&K, Hakeen Ghulam Nabi and Ghulam Ahmad Ahrar, belong to the district. Ahrar continues to have a huge following a decade after his death.

Jamat insiders say that while Hakeem was against the idea of militancy initially, he later asked his son to cross the border for arms training. His son was killed in an encounter when he was in his 20s. “Most of these new militants are from Jamat families or their sympathisers,” says a police officer. Locals dismiss the explanation of Jamat “influence” as the only reason for militancy as too convenient. They offer another.

In January this year, three civilians were killed when the Army opened fire on stone-throwing protesters at Ganawpora village of Shopian. On March 4, four civilians and two militants were killed in a late-night ambush at Pahnoo village of the district. While the Army says the civilians were accompanying the militants in a car, villagers have been saying they were killed in cold blood.

“We are left with no option but to take up arms,” says a 22-year-old masked youth, guarding a barricade he and his friends have put up. “They (police and the Army) enter our houses, beat us, ransack our homes. We can’t leave our homes after dusk or before first light in the morning. We have been reduced to slaves. Look what forced Zubair (Ahmad Turray) to pick up the gun.”

Turray, a member of Hurriyat hardliner Syed Ali Shah Geelani’s Tehreek-e-Hurriyat, was arrested under the Public Safety Act (PSA) after the 2009 protests over the alleged rape and murder of two women in Shopian. In May last year, the 24-year-old escaped jail to join militancy. Two weeks later, he released a video in which he says, “Oppression forced me to do it… I was under custody for four years. In these four years, PSA was slapped against me eight times. Whenever… my father made efforts (for my release) and my PSA was quashed, they would slap another PSA against me… When I could not see hope, I had only one way — to join the Mujahideen.” Turray was among the militants killed on April 1 at Draggad. Says his father Bashir Ahmad Turray, “I told police you turned my son into a militant.”

“Why would police harass anyone?” asks Shopian SP Dinkar. “Turray was a motivator and instigator and had a long criminal record. He was a notorious stone-pelter who had been booked under PSA several times.” The others killed on April 1, apart from Turray, Thoker and Aetimad Hussain, who joined militancy in November 2017, were Ubaid Shafi Malla alias ‘Abu Huraira’, 18, a militant since February 2017; Nazim Ahmad Dar alias ‘Furqan Bhai’, 20, and Rayees Ahmad Thoker, 21, militants since May 2017; Yawar Itoo, 18, a militant since July 2017; Adil Ahmed Thoker, 23, who joined militants in November 2017; and Ishfaq Ahmed Malik, 23, alias ‘Umar Bhai’ and Sameer Ahmed Lone, 20, who became militants just three and two months ago respectively.

The villagers have other stories of “torture” and “harassment”.

The PDP MLA from Shopian, Mohammad Yousuf Bhat, says he believes the allegations. “It is not just Shopian. Harassment is on everywhere in the Valley,” he says.

Ajaz Mir, who also belongs to the ruling PDP and is an MLA from the other Assembly constituency in Shopian, Wachi, adds, “The fear (of security forces) is everywhere.”

The villagers say the increased Army presence is only pushing more youths to pick up the gun. “One night last year, forces entered houses in several villages. They ransacked houses, beat up and arrested people,” says Showkat Ahmad Ganai, a National Conference leader from Shopian and an MLC. “In that week alone, 10 boys joined militants. That was the reaction to the harassment.”

In the three days following the April 1 encounter, adds MLA Mir, three more youths have taken up arms. Pointing to the futility of dealing with the problem “through the might of the gun”, Mir says, “They (the Government of India) don’t want to resolve it. They have been only managing it. They managed it for some time. Now, they are not even able to manage it. You have killed 210 militants in a year, but what is the result? I have said this in the Assembly too.”

***

An army personnal walk during a gun battle between suspected militants and security forces in shopian, south of Srinagar. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

An army personnal walk during a gun battle between suspected militants and security forces in shopian, south of Srinagar. (Express Photo by Shuaib Masoodi)

The way forward is only one, say the PDP legislators and the NC’s Ganai. “The problem is the Kashmir issue. You need to treat the problem. But no serious step has been taken in this direction. People want the issue to be resolved but nobody is interested in New Delhi. We have to involve Pakistan,” says Mir. He adds that PDP chief and Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti has been regularly calling for this. “This (resolution) can be done only by the Centre. We can only become the bridge.”

Meanwhile, worry the leaders, the space for mainstream politics is shrinking every day. “Our MLAs can’t even visit their homes,” says Mir. “There is no question of political activity.” Ganai points to the huge public presence at funerals and encounter sites as another worrying sign. Many do so risking their lives, he says. “You need to see how angry people are. At Kachdora, the Army had to leave an encounter site midway. People managed to retrieve bodies of two of the militants. Their bodies and guns were later taken out from the debris by the people.”

A few days ago, the funeral for Ubaid Shafi, a militant killed in the Draggad encounter, drew around 10,000 people, from Shopian and afar. Two youths in their late 20s, one of them an employee at a private school and another a graduate, sat on the sidelines. Shaking their heads at the people milling around, they wondered where it would all end — a question not many in Shopian are willing to hear right now.

“Is this the right direction we are going in?” said one. “How long are we going to lose our young men, the most promising, educated boys of our society? We need to re-strategise. The bloodshed must stop. Our leaders must rethink. The government must respond.”