Siddhartha Mukherjee, oncologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, with The Indian Express Deputy Editor Seema Chishti (right) and Senior Editor Paromita Chakrabarti.

Siddhartha Mukherjee, oncologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, with The Indian Express Deputy Editor Seema Chishti (right) and Senior Editor Paromita Chakrabarti.

This edition of Express Adda in New Delhi hosted oncologist, scientist and writer Siddhartha Mukherjee. In a discussion moderated by Deputy Editor Seema Chishti and Senior Editor Paromita Chakrabarti, Mukherjee spoke about gene editing and Artificial Intelligence as the new frontiers of medicine, the ethical implications of both and why he writes.

On writing as a form of thinking

Some people think to write, I write to think. It is a mechanism for me to lay down on a page and organise, by laying down on the page, some ideas about what we are and where we are going. Perhaps, the illuminating thing that virtually all physician writers have discovered is that medicine allows you to do this in a way that no profession does, and no other calling does — the intimacy that you can share with what it means to be a human being today.

On genetic reading and writing and Artificial Intelligence

Over the last four or five years we have acquired technologies to change and interrogate the human genome with the kind of facilities that we didn’t have before. There are two things coming out of this. One thing is that we were struggling in medicine, biology and sciences to explain the nature of human variation. We knew there were powerful genetic components to this, but we didn’t know what those components were and we are now beginning to know those components. But, we seem to have now crossed on to a new arena of limits. I call this the process of reading. It is simultaneously exhilarating but very dangerous. Writing takes a deeper step into the exhilarating abyss of human biology. Writing means we also have the capacity to begin to change the information. We can certainly delete genes, you can reactivate a gene in a human embryo, in a sperm-producing cell or an egg-producing cell, and almost certainly delete a gene that might predispose you to breast cancer. Deleting is not a problem, replacing it with a new one is at the threshold. We are about to cross the threshold. You can decide whether it is a line in the sand or not. For me it is. Artificial Intelligence is a complex field. I have some strong reservations about it. So, if I were to identify two arenas where we are drawing strong lines in the sand about what the human future looks like, it would be reading and writing genes and it would be Artificial Intelligence. It is the combination of these two things. It is when computers begin to read us, when we, rather than becoming the supervisors, become subjects of our robot overlords, that is when I suspect, for all of us, our level of discomfort rises.

On genetic engineering and its moral implications

If we are talking about genetic changes and genetic engineering, three arenas need to be distinguished.

The first arena I will call all other species, the rest of them — that is a little bit like saying that the world is divided into cows and non-cows! Interventions have already started and, in those species, the attempt is to change the species.

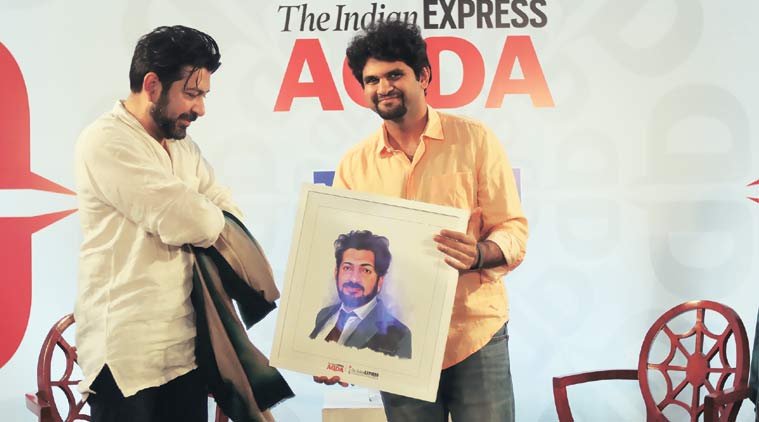

Anant Goenka, Executive Director, The Express Group, gifts Siddhartha Mukherjee a painting made by CR Sasikumar, Chief Illustrator, The Indian Express

Anant Goenka, Executive Director, The Express Group, gifts Siddhartha Mukherjee a painting made by CR Sasikumar, Chief Illustrator, The Indian Express

So, by all other species, I mean mosquitoes, crocs, fish. All these species are open for potential genetic engineering in large parts. The main dangers in doing that are ecological. So, the main dangers are biohazard and the main concern there is human humility. We should be humble about our knowledge and a lack of knowledge of the ecosystem. We want to make changes in the ecological world for good reason, I suspect. We could go horribly wrong, but we need to have mechanisms to remind us how to keep those practices safe. The second category is called somatic gene therapy. Here, we are trying to make genetic engineering in cells that are not permanently moved to the next generation. The third arena is the most complicated and is called germline engineering. And, here you are changing not just any cell in the body but cells that make sperms, eggs or embryos themselves. Here the bright-line distinction is that whatever change you make will be transmitted across generations… there are strong moral hazards. Should we be playing with our own genomes? We certainly haven’t done it in the past. Should we have the humility in the face of the capacity to change our genetic information? Could we have profound effect on ourselves as a species in the way that we self-determine our future? Should we stop now?

On modern medicine and mortality

This has been debated a lot by a series of physician-writers, including me. Atul Gawande more famously, and recently Oliver (Sacks), Paul Kalanithi, have tried to remind us to keep a certain sense of balance — personal balance between understanding the medical progress that has been made and balancing it against things like dignity around death. I think imagining societies, where progress in medicine is portrayed in an adversarial relationship with dying with dignity, is certainly possible. We know such societies exist, we’ve certainly seen them. But it’s also possible to imagine societies where progress in medicine is not in an adversarial relationship with death and these two things can coexist and we’d like that to be India.

Siddhartha Mukherjee. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

Siddhartha Mukherjee. (Express Photo: Neeraj Priyadarshi)

On cancer’s long shadow

This has to do with the idea that more than really any other disease, the fundamental mechanism of cancer builds on vulnerabilities of our physiology as a human being. In other words, the very genes that allow us to become who we are, to grow, to repair our wounds, to heal ourselves after we are injured, corruptions of those very genes enable that cancerous growth. The consequences are very clear. There is no free lunch in the human genome. Our capacity to be multicellular, all the things that make us who we are, our capacity to resist the depredations of the environment, of injury, if you just flip them over as if it were a card, inevitably it would lead to cancerous growth. Its consequences have already been felt in the West, for certain populations they are being felt in India. There is no doubt in my mind that cancer will reach, what you might consider epidemic proportions, in India.

On the state of public health in India

Cancer begins with prevention and that is driven by public health. And virtually all successful attempts of cancer prevention have been attempts by government. In India and other places, cancer prevention begins with limiting carcinogens — tobacco is the main one there, rampant in India, very poorly controlled. Other examples of cancer prevention include some degree of success in vaccination. There are viral cancers that we can vaccinate against. As you know very well, despite many efforts, efforts for vaccination against human papillomavirus have stalled. The rejection of medical science here is a real embarrassment. Science is not fake news. It’s real news for people. Rejection of this, based on rather flimsy criteria, I would say, is a real embarrassment and I hope this gets redressed.

The second arena, which tends to be a public-private collaboration, is in early detection of cancer. We don’t do very much of this at all in India. We are quite further behind. Even in nations like Cuba, early detection has taken off quite well. The third is treatment. Of course, here it goes without saying that we really lack the infrastructure. We don’t train oncologists. I don’t know how many oncologists are we training in India per year. What’s the number? A hundred, 200, 300 cancer doctors, where the need is in the order of several thousand.

A packed hall at the Adda

A packed hall at the Adda

On whether faith and science can coincide

Personally speaking, I’ve been agnostic for a while. I’ve become progressively more agnostic. I have an interest in helping people. I’m interested in small metaphysical questions. I’m not interested in large metaphysical questions.

On becoming a doctor

It came to me slowly. Nobody really knows what they want to be, we retrofit it to what we become. I wanted to be a scientist for a while, I found it exhilarating, but somewhat isolating.

On being a trained singer

Yes, I sing, I have a band, which sort of does an intersection of jazz and Indian classical music. The band is called Jog Blues, after Raag Jog.

***

VOICE NOTES

Shahid Jameel

Shahid Jameel

Shahid Jameel CEO, The Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance

You spoke about how computers can do what humans do. Will computers get cancer?

That’s an interesting idea. Computers can get infected, viruses and so forth. Learning algorithms don’t have a growth component. In an imaginary sense it would be hard to imagine what would cancer be without growth. Perhaps you can widen the question and ask if an algorithm can have dementia. I suspect they could.

Shekhar Bhatia

Shekhar Bhatia

Shekhar Bhatia Mediaperson

If you were to write science fiction, how will it end — in hope or in a dystopian world?

I have been toying with the idea of writing science fiction, I have been very inspired by science fiction, I have read science fiction all of my life. When you write a novel, you let the book become your guide, you let the characters speak back to you. Once you create them, you have to let them speak back to you. In fact, it goes back to the question —what’s the process. The process is you let the book speak back to you.

I do not know when that book will end.

Deepak Pental

Deepak Pental

Deepak Pental, Former VC, University of Delhi

We are accumulating too many mutations because natural selection is not operating. Medicine is protecting people from purifying selection. What you think?

Before an intervention, I think humility is required. We lack that humility currently. I think what distinguishes us from animals right now is the capacity to care for the ill. I have been an advocate of humility, because out attempts to tamper with selection have gone quite badly in history. It is not clear to me the forces of natural selection have been entirely removed. I hope we can eliminate diseases through genetic means but the desire to recreate and craft human genome have been projects that have gone wrong in history. I feel we should be humble in the face of all that.

Soli Sorabjee

Soli Sorabjee

Soli Sorabjee, Former Attorney General of India

You mentioned jazz. Does jazz really help you — the jazz of John Coltrane, Miles Davis?

These are big names. Anyone who has spent some time thinking about Indian classical music understands that there are rich intersections with jazz. I would like to think how these might have evolved. If you imagine music as a kind of genetic strain, as a metaphor, how could these two types of music, which arose in totally different places, have evolved in directions that are surprisingly similar? What could it tell us about humans if we want to listen to something created on the spot? It’s a fascinating idea.

Nasim Zaidi

Nasim Zaidi

Nasim Zaidi, former Chief Election Commissioner

My job is with election manifestos. I want to know what will be the top items of the manifesto of genome history in the next 50 years?

We are trying to understand how humans are different and similar from one another, how our DNA contributes to human similarity and difference. It can range from trivial questions — why is your face, hair colour different from mine? But, of course, the rather profound question is why do you suffer from a disease and I don’t. High on the manifesto is that, if we had the information, should we, would we, could we, in that order, change this information?

Sunita Kohli

Sunita Kohli

Sunita Kohli Interior designer and architect

Is there a set time to your writing?

I try to carve out time every day if I can, write something every day. Most people who write realise, over time, that the real place for writing is editing. It’s what you take away from the page than what you leave on the page that is important.

Nalini Singh

Nalini Singh

Nalini Singh, Mediaperson

Is there a happiness gene. And can you intervene?

I wish there was. But there isn’t. I will give you a gene for happiness if you can define what happiness is.