“That larger reality is already well-established. We know it so well that it becomes impersonal. My aim is to personalise it. How is the individual who is unique relating to that reality?” – Anjum Hasan

“That larger reality is already well-established. We know it so well that it becomes impersonal. My aim is to personalise it. How is the individual who is unique relating to that reality?” – Anjum Hasan

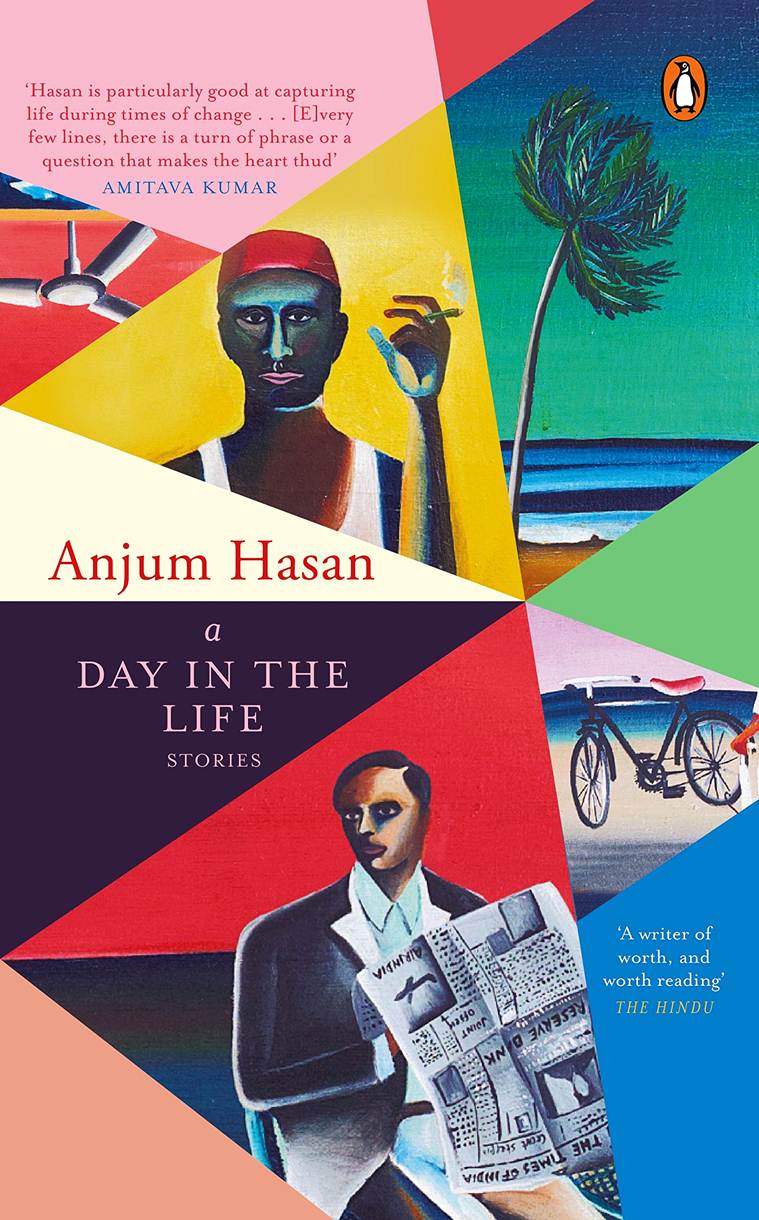

You have dedicated your new collection of short stories, A Day in the Life (Penguin-Hamish Hamilton) to (poets) Vijay and Kavery Nambisan…

He was a dear friend and I really miss him (Vijay Nambisan passed away in August 2017). He was a quiet writer, a lovely poet, very quirky. He didn’t fit into any easily available categories. Now, everything is so professional — we are professional poets and professional non-fiction writers — he wasn’t professional anything. He worked against the professional, in fact. He was erudite for the sake of erudition — I feel I don’t know too many people like that any more in the literary sphere. He was very precious.

How do you work on short stories? Is there a thematic link that you determine beforehand or do you put them together when you are finally done?

The stories have been written over three or four years. I don’t really work on books of stories, I haven’t so far. I work on the story because I have figured by now that I have broadly a particular kind of interest that will form some kind of an argument for a book.

There’s a bit of you in a few stories in the collection, isn’t there? Is that because you are more confident now of putting yourself out there?

I think so, which is strange, because I started out with poetry which is more personal. I really wanted to not write about myself and poetry can be a quiet, inward-looking form, so, writing novels was a way of moving out of that. And even though you use little bits of things you know or places you have grown up in, you are not bound to that. You are writing fiction. But now, I am starting to get curious again about what does it mean to write about the personal in fiction. I am trying also to intrigue the reader. I am trying out different forms within the broad genre of the short story. One of the ways you can stretch it is to bring more autobiography and still be telling a story, and, also, to do autobiography in a non-literal way. I am not talking about any significant chapter in my life or something big that happened. I am picking out themes, which are, in a way, almost frivolous, like eating or style, very ordinary everyday things as a theme to tell the story of your life. I am also playing with the idea of autobiography itself. Autobiographies can be ponderous and grave because you have something significant to tell about your life and I don’t, so I am working against that assumption of autobiography as a profound form. It can also be a playful way to tell stories about yourself.

Since you mention that ‘A Short History of Eating’ from the collection as autobiographical, I have to ask you this: are you interested in food?

I love to cook, but I am not a foodie or a gourmet cook. I am not interested in food as a speciality or as lifestyle, I am interested in food as sustenance. I love to cook as a way of doing something with my hands and also because of the necessity of feeding myself. We don’t have servants and I think it’s nice to get back to reality, to be in touch with something basic like who needs to get the grocery. I like the dailiness of that. It keeps you humble.

You are also a literary critic. How does that play out when you are writing?

I am more interested in histories, literary histories, connections, traditions — like maps, how do you connect the present to the past in literature. I am interested in what of my reading and my environment are informing the story more than critical theory. I am not a very self-conscious writer. I do believe in intuition, serendipity, things creating a pattern in my mind without knowing how. I don’t want to sound mystical about it, but I like the magic of things to create the story for me, so I am doing the work of the writer, but I am letting life suggest things. If the shape of your imagination is through stories then life starts suggesting itself in stories. It becomes like a receptacle and things start falling in that pattern.

When I read your books, I am always struck by the detail that goes into your description of houses. Am I reading too much into it or does the house mean something to you?

It seems to, I don’t know why. I grew up in a Shillong which still had a lot of these older cottage-type of houses, which I loved and which are now going. I grew up in a series of them — we kept moving when I was very small, maybe that is the reason. I am fascinated by architecture and how a space can become your own and how you make a space your own. Actually, I am obsessed with space — houses, of course, but it can also be nature. I have to establish the space and the place in my work. I am interested in a place as an observer than as an insider. There are writers for whom everything is local because they are in it; they are able to establish it as a very rooted thing. But then there are other kinds of writers who are describing it as the environment. It has an emotional quality still, it’s not just the furniture of the story — what kind of houses are the characters in, the weather— all these things add a texture to the story.

Anjum Hasan’s book, A Day in the Life.

Anjum Hasan’s book, A Day in the Life.

And what do you see when you examine space in contemporary India?

A lot of young people don’t have a strong sense of space because we move about so much, especially the middle class. I keep meeting people who declare that they don’t want to leave their houses. I am fascinated by it. It isn’t easy to live in an Indian city and now we are all living lives that enable us to get things done without moving about much. I know people who do that, who will not even walk in their neighbourhood. They will travel a lot — get into the car, go to the airport, to the mall, and, perhaps, to another friend’s place that is like their place. That’s it. It is understandable at one level, but it also alienates us from other kinds of lives. It’s very important for me to simply walk about, though increasingly, just the physical act of walking in our cities, be it Bangalore or Delhi, is becoming so hard. I am obsessed with contemporary things, how we lead our lives now. I am trying for that to inform my writing.

The line between being solitary and being lonely is rather muddled now, isn’t it?

I guess I am fascinated by loners, but I am also interested in people who are not conventional loners. In the story ‘I Am Very Angry’, for instance, TS Murthy, has led a very regular life in a middle-class job. He’s not a very angsty person. But after retirement, something about the condition of contemporary India makes him lonely. Sometimes, loneliness is thrust upon us, sometimes, we seek it out. There are different kinds of loneliness around us.

Most of your characters have an interiority, a rich inner life…

I think people are like this, that they think and experience moments of doubt and anxiety. When you are not just playing a role or doing expected things, or, when the narrative breaks, you ask yourself, ‘who am I’. For me, it becomes very important because fiction seems to be the last place where you can explore that. We are so busy writing about important things, who is going to write about feelings? That human uniqueness where everyone actually is a little different though they all have similar lives, for me that is the stuff of the story.

Where does that leave the larger political narrative though?

That larger reality is already well-established. That’s what we hear about in the news cycle. In fact, we know it so well that it becomes impersonal. My aim is to personalise it. For me to be able to humanise it, I need to focus on the smaller things. The news is in the background. How is the individual who is unique relating to that larger reality?

Do you write every day?

If I am home, and I am not interrupted by travel or family stuff, then I usually write from 9 am till 12 pm. I try to keep that time off-limits for anything else. No internet, no phone calls. Even if I go online for half an hour and then try to write, it’s harder. To write fiction is to create illusionism of a kind and you have to withdraw a little. I just can’t go from a phone call to writing a sentence.

How often do you return to Shillong?

My parents live there. I lost my dad last year, so now it’s just my mum. I go back every year, sometimes twice a year, usually at least for a month. I don’t know what it’s going to be like with my mum alone, we are still figuring it out. I have four siblings, we all try and overlap when we are there. I love Shillong deeply, but I also feel it’s changing very much. But I do want to write more about Shillong. It’s still one of my inspirations for sure.

Indian writing in English also tends to compartmentalise itself — ‘writers from the Northeast’, ‘small-town writers’. How do you react to these terms?

I don’t want to limit myself in terms of subject matter or where I come from. I don’t think these categories are useful for a writer. Maybe they are helpful for someone who wants to read more from that region. Also, I don’t think it should be an absolute category. People from the Northeast are also writing novels set elsewhere and someone who is not from the region could write about the Northeast. The application of these ethnic categories to writing also becomes like, ‘Oh we are the under-represented part of the country, we are the ignored writers’ — literature doesn’t work too well with that.

The narrative of the Northeast being marginalised is getting a little jaded. I don’t think the Northeast is off the map any more. So, for me, the question is what form does this curiosity take? Also, what about the people in the Northeast? Are they curious about themselves? Are they reading these books? Not very much. What about the literary culture in the Northeast? We are always looking out, it’s almost like the government of India mindset — you have to take care of us. But you can’t apply that formula to literature. Every writer should speak for themselves and ask themselves what is their place in their literary culture. How are they modern? How are they not just from one region and one language?

Have you completely moved away from poetry?

I am not really a full-fledged poet any more. I love poetry very much and I really want to go back to it, at least to reading more of it. Poetry is my foundation. I think it’s there in my prose, in the craft of my sentences. A beautiful sentence obsesses me.

What are you reading now?

I am reading a lot of Urdu fiction in translation. I have gotten interested in translations from Indian languages. There’s so much going on, how do we make sense of this? I read in a very eclectic way. I don’t read all the latest books that have a buzz around them. I read much more out of my own needs. I don’t think novels are topical matters, they are not the news. They are of their time, but that time can be a few years, if not a decade. I am not driven by the marketing of books. That is boring to me.

Is that why you also stay away largely from social media?

I am on Facebook, but merely to share information about my work or events. I don’t see the point of expressing opinions on Facebook. I’d rather save my opinions for my stories. I am not on Twitter or Instagram. Social media has a way of making you feel that you constantly have to catch up and I don’t want to be part of that.